By Armin Behroozi

Imagine a low-income worker heading home after an exasperating, labor-intensive day. Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, he is deprived of adequate transit options and food market choices. Too tired to walk several miles over to a neighborhood with a supermarket, he must settle again for the liquor and convenience store several blocks away from him.

What will he find at this convenience store? A smattering of junk food and highly processed foods await him. The few goods that are not processed, among them a box of pasta and a jar of tomato sauce, are priced extremely high- the owner knows that other pasta, much less cheaper pasta, cannot be found anywhere else nearby. Say our worker was to end up buying a microwavable burrito or a frozen pizza, and say he were to do this often. What kind of harmful health effects would he and his family eventually suffer from, and how can his dilemma be solved?

America’s complex tale of inner-city neglect has lead to a myriad of health problems that plague the country’s cities. The average American city has an obesity rate of 25.3% and a diabetes rate of 9% (“Socioeconomic Significance of Food Deserts”) , revealing that health should be a serious concern in the inner city. In an attempt to understand why these rates are so high, this post will look at some of the factors identified in food deserts that lead to bad eating habits, and eventually, bad health. These factors include physical food selection and food culture.

Food Selection

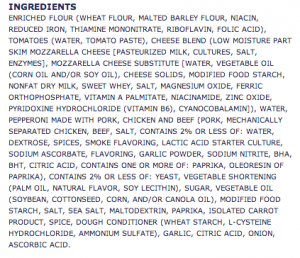

The foods most commonly found and consumed in convenience stores and other limited-service groceries are highly refined wheat products, potatoes, fatty meats, whole fat dairy, refined sugars, sweetened carbonated beverages, and beer (Darmon et al. 9) . This means that the patrons of these convenience stores both rarely encounter and consume more wholesome foods such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, lean meats, seafood, and low-fat diary.

Because of a high fiber content and high level of glycemic control, fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains provide a natural way to feel full or satisfied. These foods provide an unrefined source of sugars that are thought to balance blood pressure and either stabilize caloric intake or reduce it (Breneman et al. 51) . Low-fat dairy products have in turn a lower number of calories than high fat dairy products, also adding to a healthier diet. In contrast, highly processed foods such as our worker’s burrito or frozen pizza have significantly less nutrients and healthy fats and sugars, substituting them instead for harmful trans fats and chemical additives that our bodies cannot efficiently process and digest (Whitacre 40) . High-calorie soft drinks are rife with processed sugars that are stored as fat in the body. This excess fat often leads to dire health consequences: a 2009 article in Diabetes Care found that daily consumption of soft drinks lead to a 36% greater risk of incident metabolic syndrome and a 67% greater risk of incident type 2 diabetes compared with nonconsumption (Nettleton et al. 2)

It is in light of this information that one may begin to understand why the health situation in the American inner city is so dire. The processed foods offered in convenience stores have more calories, sugars, and chemical additives than the healthier options offered in full-service grocery stores. This selection of unhealthy foods leads to higher rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes among those with limited food options in inner city food deserts.

Education and Culture

In addition to the nutritional value of foods consumed, there are more intangible forces behind the higher rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes in the inner city. It is admittedly difficult to understand the eating habits of a community without first attempting to understand the culture of that community and its attitudes towards educational initiatives. Numerous hypotheses of a sociological nature have been proposed, but none of them have been verified and accepted widely.

Several theories agree that there are functional barriers to healthy eating observed uniquely among extremely low-earning families. Some of these barriers include a lack of cooking equipment and the ability to afford it, a lack of nutrition knowledge, apathy towards health warnings, and an incorrect perception of body weight. They cite limited time for food shopping and cooking as a contributing factor to these barriers (Darmon et al. 3)

Conclusion

In an attempt to encourage healthier eating habits and lower rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes in the inner city, academics and policymakers alike are encouraging more educational initiatives geared towards changing eating habits. As this post has discussed, however, there are a myriad of factors behind these habits that reinforce how complex our nation’s food problem really is. Choosing to solve our cities’ food epidemic means committing to provide cheaper, more readily available healthy food to all citizens. Once healthy food options are accessible by all citizens, cities can then analyze the cultural forces at play behind peoples’ eating choices, and work within those cultural constraints to provide meaningful health education programs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Breneman, V., Farrigan, T., & Hamrick, K. (1998). A study of access to nutritious and affordable food appendices. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis and Evaluation.

Chinni, D., & Freedman, P. (2011, June 29). The Socio-Economic Significance of Food Deserts. PBS. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/2011/06/the-socio-economic-significance-of-food-deserts.html

Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2008). Does social class predict diet quality?. The American Journal of Chemical Nutrition , 87(5), 8.

Nettleton, J. A., Lutsey, P. L., Wang, Y., Lima, J. A., Michos, E. D., & Jacobs, D. R. (2009). Diet Soda Intake And Risk Of Incident Metabolic Syndrome And Type 2 Diabetes In The Multi-Ethnic Study Of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care, 32(4), 688-694.

Whitacre, P. (2009). The public health effects of food deserts workshop summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.