By Daniela Cardenas

Part I: An Introduction to Medellin, note from the author

The Northeastern Urban Integration Project was awarded The Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design from The Harvard Graduate School of Design, due to its efficiency and potential for “thoughtfully planned and carefully executed mobility infrastructures to transform a city and its region” (Prosky, 2013).

This is the MetroCable line that is the main form of transportation for this community. The Spain Library Park is located on top of the hill. Image taken from Architecture in Development: http://www.architectureindevelopment.org/images/au/metrocable-Medellin-Colombia.jpg

The Northeastern Urban Integration Project addresses the two major issues in the northeastern communes of Medellin : inequality and violence. The Northeastern Urban Integration Plan was able to pull together a variety of ideas and create a strategy to frame and address the problems in the city. It focused primarily in the informal precarious settlements located in the northeastern slope of Medellin.

The people living in the northeastern commune of Medellin, were facing both physical and social isolation. By living in squatter settlements on top of mountains, communities were not integrated to the city as there were no roads or public transportation. They were socially isolated due to the violence hazards they faced by the presence of drug gangs in their neighborhoods.There were no social institutions to establish order in these informal and precarious settlements, and thus the culture of fearing the city was imprinted in everyone.These problems translated into higher poverty levels, and a lack of opportunity for people to get access to jobs, health care and education.

Every community was restricted to a limited radius in their daily commute precisely by the lack of infrastructure and affordable public transportation systems. Medellin, and specially the northeastern zone was extremely polarized and divided both physically and socially.Each person had a personal map of the city, which only compromised 30% of the whole area (TEDx Medellin, Urbanismo Social en Medellin, Alejandro Echeverri).

The plan implemented infrastructure to allow greater visibility of the area, and thus increased security; at the same time the construction of bridges, and public transportation systems such as the MetroCable allowed better integration of the northeastern zone with the city, and its individual communities (TEDx Medellin, Urbanismo Social en Medellin, Alejandro Echeverri). Finally the plan built community centers such as library parks with permanent cultural and educational programs to reconstruct the community that had been fragmented by violence and poverty.

Social Circuit: Spain Library Park, MetroCable and Public Space in the Santo Domingo Savio neighborhood.

Transportation: MetroCable

The Main Metro Line is the blue line, and the K-line(green) is the one connecting the northeastern zone, the brown line was recently opened and it connects the community to a natural park in the mountains.

Medellin is the only city in Colombia with a Metro system, which started operating in 1995.This has been a true advantage for people in the city as it not only decreases traffic congestion but also promotes employment as people can easily commute to work from any part of the city with the use of Metro(Metro de Medellin, 2011).

In order to better integrate the city, with the northeastern commune and target the audience living on top the hills, a cable car, was implemented as an extension to the original Metro.This project is called MetroCable and it consists of an integrated transportation system that allows people from the upper informal precarious settlements to access the inner city. This integrated transportation system costs around 1 dollar per trip and it is connected with the main Metro line of the city that runs along the river from north to south.This extension consists of a series of stations up the mountain and small gondolas fitting up to 10 people transporting them up and down the mountain and finally connecting them to the original Metro station(Metro de Medellin, 2011).

The Metro transportation system has been a great contributor to social alleviation in marginal sectors of the city, as a culture of respect and responsibility is constructed with it. People respect and value the Metro, for instance there isn’t graffiti or trash in any Metro station around the city, even in the most marginalized neighborhoods the Metro is intact(Metro de Medellin,2009)

The northeastern integration plan started in 2004, right after the implementation of the Metro Cable, and it worked very well because the Metro station was one of the few social institutions that started enforcing norms and order in the northeastern zone, and at the same time provided people with opportunities in the urban core of the city.

Education and Community Empowerment: The Spain Library Park

This new infrastructure incorporated marginalized communities that had been displaced to the mountaintops of the city, living in squatter settlements by allowing them to have easy access to the whole city. These people had constantly been disadvantaged because not only did they live in the most dangerous and violent places of the city, but also they had built homes in areas with high geological risk of landslides that was made worse by the heavy rainfall patterns in the past years. These people did not have access to jobs, as the daily commute up and down the slopes was very limited due to the lack of infrastructure and social barriers delineated by drug trafficking gangs within each neighborhood.

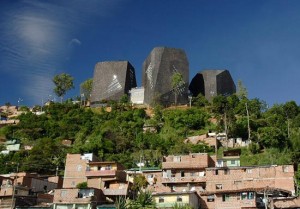

A whole circuit of transportation and public space was created around the Metro Cable, having the idea of connecting people right from their doors to their workplace or school. Around the main station of the Metro Cable on top of the squatter settlement public space, parks, and schools were built. One of the most iconic transformations was the construction of the Spain Library Park in the Santo Domingo neighborhood by a very recognized Colombian architect named Giancarlo Mazzanti.

The imposing architecture emphasizes the radical change both physically and socially within the community. This is a space where people can feel separated from the ugly truth that they usually face in these kinds of neighborhoods.

Image taken from http://www.designboom.com/architecture/giancarlo-mazzanti-biblioteca-parque-espana/

This public library was constructed in order to emphasize equity in the city. The best and most iconic architecture was to be located on top of a squatter settlement close to the Metro Cable station. This would improve the lack of institutional presence in the neighborhoods, which at the same time was one of the key factors that triggered violence in these informal settlements. The community was part of participatory design processes around the library and the public space and parks around it. Today this library serves more than 170,000 people in the nearby neighborhoods and it has community projects targeted towards all members of the community, ranging from the unborn to the elderly(Schwaller, 2012).

The library is composed of three connected blocks that have an imposing architectural design specifically designed to create a physical impact as cultural manifestation within the neighborhood. The three big buildings have a dominant presence in the urban place, and they can be seen at a great distance. One of the blocks makes up the actual library, which has a reading room with more than 12,000 volumes and 40 computers with Internet access (Schwaller, 2012). The library is divided into different floors that classify the different kinds of content for the different demographics and age groups. The other block is the auditorium, which is used as a place for community debates, shows and music concerts. Finally the third block is the recreational area, which has an art gallery and a day-care center (Schwaller, 2012) The library is not only an intellectual and educational space, but has become a social space of gathering where different ideas for improvement have surged.

This physical and institutional impact has translated into a social impact that has benefited this community and had improved the security and economy in the northeastern commune. This locality is no longer considered a dangerous or violent part of the city, in fact it has rather become a place where tourists come to see and experience the transformation of the city.

The Spain Library Park is one of the 23 libraries around the city that makeup the metropolitan network of public libraries around the most marginalized parts of the city. It is a symbol of transformation and metamorphosis in the city. It symbolizes equity as it addresses the fact that even the most marginal and poor communities have the right to have the best projects with the best buildings and architecture in the city.

Works Cited

“España Library / Giancarlo Mazzanti” 17 Jun 2008. ArchDaily. Accessed 02 Dec 2013. <http://www.archdaily.com/?p=2565

Metro de Medellin. (2011). Informe corporativ0 2011: Nuestra historia. Retrieved from https://www.metrodemedellin.gov.co/informe2011/index.php?option=com_content&view=featured&Itemid=271

Metro de Medellin.(2009).Cultura Metro. Retrieved from https://www.metrodemedellin.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=75

Prosky, B. (2013, August 26). Gsd announces winners of 2013 veronica rudge green prize in urban design. Retrieved from http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/

Ramos , A., & Allegretti, G. Comision de Inclusion Social, Democracia Participativa y Derechos Humanos de CGLU, (2007). Medellin,colombia: Comprehensive urban project- north-eastern zone. Retrieved from United Cities and Local Governments website:https://docs.google.com/a/cornell.edu/file/d/0B6fAmNgdjp5bR1l5MEt2VkxWMGs/edit

Santana , O. (2009, September 27). Proyecto urbano integral pui nororiental (integral urban plan iup) medellín, colombia. Retrieved from http://openarchitecturenetwork.org/projects/puimedellin

Schwaller, N. (2012). Parque Biblioteca España. Retrieved from http://www.architonic.com/ntsht/parque-biblioteca-espana/7000385

TEDx Medellin. (Producer). (2012, April 03). Urbanismo Social en Medellin, Alejandro Echeverri [Web Video]. Retrieved from http://tedxtalks.ted.com/video/TEDxMedelln-Alejandro-Echever-2