By Garrett Craig-Lucas

Located at the confluence of land and water, urban waterfronts possess unique characteristics due to ecology, economic histories, and associated development patterns. While many urban waterfronts suffer from economic and physical decline as industrial uses recede, exciting opportunities arise for redevelopment. The relationship between the city and the water’s edge creates a series of economic and environmental constraints that influence use and development. The contributing factors to these constraints are also what provide post-industrial waterfronts with qualities of place that are intriguing and desirable. Former industrial uses leave behind large buildings, warehouses, and infrastructure, creating a unique urban form that can often be revitalized to support new economic and social centers. Exploring the history of urban waterfronts with a particular focus on land use and zoning will provide insight into how the waterfront landscape developed and how it can best be utilized as it is repurposed and redeveloped.

Historical Overview: Land Use, Zoning, and Industry

Many land use plans and zoning ordinances for waterfronts still reflect traditional uses related to maritime industry (Wrenn, 54). This includes shipping and manufacturing, as well as related business and service sectors that support and rely upon these industries. With major shifts in the ways shipping and manufacturing occur and the places where these processes are able to occur, many ports and urban waterfronts cannot retain these longstanding economic drivers. In order to understand how planners and developers have begun to redevelop the waterfront and approach outdated land use and zoning regulations, it is necessary to understand historical land uses, how and when zoning was implemented, and how it has developed. In order to understand this I will explore the major shifts in maritime industry that caused these original ordinances and uses to become antiquated. This can be achieved using the concept of the port-city interface as a framework for analysis.

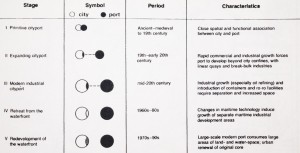

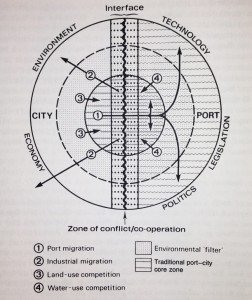

One method of understanding the progression of land use on the waterfront is through the concept of a port-city interface (Hoyle, 6). The port-city interface addresses the relationship between port and city, particularly spatially and economically. The pre-industrial city-port had a close linkage spatially and functionally. Industry and commerce grew tremendously between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries, expanding the port, causing it to begin to move out of the historical urban center. The most influential factors in the retreat of maritime industry from the waterfront were related to new technologies in shipping, particularly containerization and bulk terminals, which emerged in the 1960s. Changes in technology have resulted in increased ship sizes and the need for larger sites on land, resulting in a more extreme separation of the port and city. These changes often caused the historical port center to become run-down and partially abandoned. Conditions are thus appropriate for renewal and redevelopment. The possibility for new land uses exists and there is the consequent need for new visions, plans, ordinances, and zoning.

Keeping this timeline of the progression of the port-city interface in mind, the implementation and function of zoning can be analyzed in a way that provides insight into current problems related to zoning and waterfront development. The first zoning ordinance was adopted in 1916 in New York City (Elliot, 9). The form of zoning that the city implemented is called Euclidean Zoning, which divided the city into parcels, represented by colors on a zoning map. While a variety of problems have resulted from this form of zoning, it has been the foundation of many US cities in terms of a method for controlling land use (Elliot, 15).

Current Trends and Initiatives

In order to address this problem, a number of solutions have been developed. Rezoning the waterfront has been approached in a variety of ways. A special waterfront planning area can be designated in the city master plan, a waterfront zone can be adopted as part of an existing zoning ordinance, or criteria and performance standards pertaining to waterfront characteristics can be developed (Wrenn, 58). Zoning bylaws, overlays, and incentive zoning are other methods used to overcome restrictive zoning codes. Another method, districting, allows for the government to meet the specific needs of a geographic area. This can allow for economic development districts, historic districts, and mixed-use development districts.

Mixed-use is one of the more popular and most recent approaches to urban development which combines a variety of land uses into a large scale, comprehensively planned project (Wrenn, 59). This method of development allows for the implementation of many uses and services within close proximity, allowing for the transformation of severely deteriorated areas into functional urban centers.

Banner Image (top of page): Container ship Ville D’Aquarius docked at Port Newark Container Terminal located in Port Newark, N.J. The photograph provides a sense of the magnitude of the contemporary port industry, and thus why it is not possible for this industry to be located in many historic city-port centers such as Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Source: ABC News (2012).

Sources

Elliott, D. L. (2008). A better way to zone: Ten principles to create more liveable cities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Hoyle, B.S., Pinder, D.A., & Husain, M.S. (1988). Revitalizing the Waterfront. Great Britain: Belhaven Press.

Wrenn D. M., Casazza, J.A., & Smart J. E. (1983). Urban Waterfront Development. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institue.

Additional References:

Craig-Smith, S., Fagence, M. (1995) Recreation and Tourism as a Catalyst for Urban Waterfront Redevelopment: An International Survey. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Hoyle, B. (2000). Global and Local Change on the Port-City Waterfront. Geographical Review, 90(3), 395.

Kokot, W. (2009). Port Cities as areas of Transition–Comparative Ethnographic Research. Port Cities as Areas of Transition. Ethnographic Perspectives, 7-23.

Perkins Eastman (2013). EE&K a Perkins Eastman Company: Waterfronts. Retrieved from http://www.eekarchitects.com/portfolio/1-waterfronts

Petrillo, J. (1987). Small City Waterfront Restoration. Coastal Management, 15,197-212. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08920758709362028

Salkin, P.E. (2005). Integrating Local Waterfront Revitalization Planning into Local Comprehensive Planning and Zoning. Pace Environmental Law Review, 22 (2), 207-230. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pelr/vol22/iss2/1

Sieber, R. T. (1991). Waterfront Revitalization in Postindustrial Port Cities of North America. City & Society, 5 (2), 120–136. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/city.1991.5.2.120/pd

World Port Source. (2013). United States- Satellite Map of Ports. Retrieved from http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/USA.php

Wrenn D. M., Casazza, J.A., & Smart J. E. (1983). Urban Waterfront Development. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institue.