By Jiachi Zou

Water is essential for life. In addition to its important role as a natural resource, water directly affects human health and vitality. In this way, water supply counts as a significant sustainability issue in city planning.

Demand of water could never be low. Irrigation, industry, and households all require water, adding pressure on freshwater supply. An initiative, “Water for Life” decade in the United Nations Millennium Declaration was announced to make a more sustainable use of global water, with an emphasis on the access to safe drinking water. However, the fact is that nowadays, around one billion people do not have access to reliable drinking water. Moreover, population suffering from poor sanitation amounted to over 2.5 billion (Barth et al., p.221). Groundwater, as an important source of drinking water, has only a small part of it usable, because only deeper groundwater is of high salinity. What’s more, as Barth reveals, since “most subsurface processes are slow and memorize impacts over generations, only far-sighted groundwater use and protection is sustainable” (p.221).

The water supply predicaments can be reflected in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area’s water supply story. Overall, the Mexico Water Aquifer is being over-exploited, and difficulties such as the decline of ground water had made the aquifer and water distribution system vulnerable to contamination. We can examine the city’s water supply, water quality and health concerns in order to obtain practical recommendations to improve Mexico City’s water supply and reach sustainability.

Accessing Safe and Clean Water

Sources: The World Bank Photo Collection on Flickr

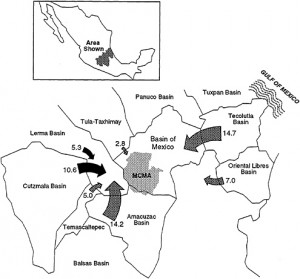

Management of water and water service in Mexico City Metropolitan Area (MCMA) is provided by the Federal District and the State of Mexico. Their water service causes a large amount of water leakage. The loss amount, as acknowledged by the National Water Commission, could be as high as 40 percent in some parts of their service area (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.21). Among their water resources, a majority comes from well fields in the Basin of Mexico, which exploit underground water. Surface water in the basin only contributes about 2 percent of water supply. So we can conclude that a dominant water resource for MCMA is underground water. However, by the 1930s, groundwater supplies within the Basin of Mexico were being over-exploited, and the city has faced the challenge to explore new water resources outside the basin. As a result, in 1941, Mexico City began to build a 15 kilometers long aqueduct to transfer water from wells in Lerma Basin to the city and the basin. In addition, in 1982, the city initiated a project to transfer surface water from the Cutzamala River Basin, with a distance of 127 kilometers and an elevation of 1,200 meters. Now these two projects are combined and contribute to a total of 26 percent of water supply (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.22).

MCMA’s Water Resources, by the National Water Commission.

Regarding the difficulty of supplying sufficient water and the huge size of population, Mexico City depends on the aquifer for nearly 3/4 of its water supply and therefore, it is hard to protect ground water from contamination (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.39). Various human pathogens and toxic contaminants can penetrate into the ground water and lead to a big concern with human health. There are several possible causes of water pollution. First of all, the MCMA acts as one of the most important industrial districts in Mexico. As it produces around 45 percent of the nation’s industrial production, we can expect a tremendous amount of waste generated that is not environmentally friendly. The National Institute of Nuclear Investigations estimates that the Federal District creates about 3 million metric tons annually, of which over 95 percent are effluents discharged to municipal sewage system (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.41). Despite the existence of national laws and regulations that require control on hazardous wastes, the MCMA’s waste management is poor due to the lack of facilities for recycling, treatment, and disposal. Apart from industrial waste, pesticide application in agriculture is another threat to water quality. The Pan American Health Organization (1990a) has identified the Lerma River, which offers a fraction of drinking water to Mexico City to have pesticides problem (p.41). We have concluded before that underground water from well fields occupies a majority of the city’s water resources. Unfortunately, the State of Mexico reports that 23 percent of its water supply wells for service area fail to meet the standards for coliform bacteria, and 11 percent do not meet the standard for inorganic constituents. The Federal District also has similar water quality problem. To respond, the Federal District either performs additional treatment such as oxidation, filtration at the well head or closes those polluted wells (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.44). As I mentioned before, there is leakage loss in the water distribution process. It can lead to concerns with water quality and supply in a way that, as the case study indicates, “when the soil is permeated by sewage from leaking sewers or from other sources, such as unlined canals carrying sewage, then leaky pipelines will be infiltrated with contaminated water when pressure is low” (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.46).

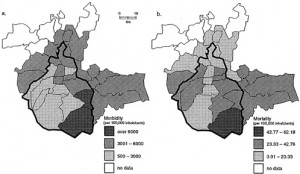

An intimidating result of water supply contamination is the disease. In MCMA, the major health concern related to water is infectious gastro-intestinal diseases, which children are especially vulnerable to. These diseases often cause acute diarrhea and at times death from dehydration. In 1991, census date reported that this sort of disease is the third leading cause of infant mortality in the State of Mexico and fourth in the Federal District. In a nationwide aspect, it can be the second leading course of infant mortality (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.49).

Morbidity (a) and mortality rates (b) due to acute diarrhea in the general population by county in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. By sanitary jurisdiction

Apart from infectious diseases, Mexico City also suffers from toxic chemicals as an industrial city. Some chemicals result in acute or chronic toxicity, and others can be genotoxic, “producing carcinogenic, mutahenic, or teragenic effects” (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.52). In a word, water quality matters significantly in public health and in maintaining a vigorous city.

From the case study of Mexico City’s water supply, there are implications for water supply patterns. As groundwater is being depleting over time, the lack of usable water resource is an overwhelming threat in sustainability. In Mexico City case, there is unaccounted water loss in the process of distribution; therefore, it is urgent to develop improved distribution system that can reduce such loss. In addition, over-exploitation of ground water increases the risk of the aquifer being contaminated and causes health concern. Other than finding new water resources, we can effort to decrease water demand. For example, reclaimed and treated municipal waste water could be used for urban and industrial uses including agricultural irrigation, and aquifer recharge (Mexico City Water Supply Committee, p.81). In all, water supply is an important factor in planning sustainable city. We should invest in more researches and long-term programs to eliminate water-related environmental and social problems.

Works Cited

Barth, J.A.C et al. (2010). “Global Water Balance”. Linkages of Sustainability.(Graedel, T.E. and Ester van der Voet. Eds.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Joint Academies Committee on the Mexico City Water Supply. (1995). Mexico City’s Water Supply: Improving the Outlook for Sustainability. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.