By Patrick Braga

“A man crosses Boulevard Mohammed V in Casablanca’s French colonial era New Town” – Mark Henley / Panos Pictures, 2009. ARTstor.

(For a historical background on this historiographical and theoretical analysis of the story of Moroccan urbanism discussed in this post, please read The History and Legacies of Urbanism in Casablanca first.)

Modernism, modernity, and modernization as intertwining concepts have shaped the trajectory of development and growth in Moroccan cities. Acting within a context of colonialism and its accompanying ‘white man’s burden’ to provide the colonized with the benefits and welfare that accompanied European technology, Casablanca is an example of a misguided application of planning principles that adhered to an imposed, foreign aesthetic and an artificial and self-negating dichotomization of modernity and tradition.

Within the realm of architecture and planning, modernism can be defined as a physical design movement of the early- through mid-twentieth century that sought to respond to the environmental and social inefficiencies of the nineteenth-century city. The movement held to the goal of generating ever-new forms of building that made the highest use of latest technology while providing healthful and comfortable living for all the inhabitants of a city. Art historian Mark Crinson (in von Osten 2010, 19) defines the characteristics of modernist architecture as “that embrace of technology, that imagined escape from history, that desire for transparency and health, that litany of abstract forms.” Von Osten (Ibid.) notes that modernism created a universal architectural language that had the promise of delineating a “common trajectory” and architectural/aesthetic language for all cities that enter the political and economic social structures associated with globalization.

Within planning more specifically, modernism is exemplified by Tony Garnier’s model of the “Cité Industrielle” (in Rabinow 2013, 58), which Le Corbusier saw as a precursor of high modernism and which colonialists such as General Lyautey in Morocco adopted wholeheartedly. Under this view, the region is a fundamental spatial unit that must be zoned according to areas of work, housing, health, leisure, administration, history. (Parenthetically, only with the 1984 Master Plan would Casablanca explicitly work towards reducing separation of land uses in an attempt to improve quality of life [Journady 1999, 99]). As explained in the history post, the French experimented with such new ideas in Morocco (as per Maghraoui 2013, 6) to make sure that their vision for the European city, composed of “vast open spaces … broad boulevards, water and electrical supplies, squares and gardens, buses and tramways” (Wright 1991, 87-88) could succeed. In short, then, modernist architecture and planning act as an approach to spatially organizing the new “industrialised [sic] way of living, working and consuming” of the contemporary age from local to regional scales (von Osten 2010, 19).

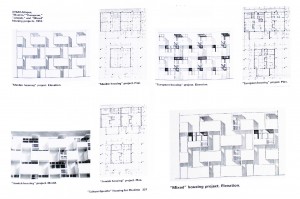

Carrying on, modernity is the idealized état d’être characterized by the adoption of modernist ideology in the built environment and as a tool to respond to social issues. Accompanying modernity is the adherence to “industrialization and standardisation of aesthetic forms” (von Osten 23), which to this day are taught as a way to create perpetually novel and ever-updated built environments. Beyond aesthetics, underlying modernist ideology is the creed that social progress was plannable. Indeed, according to Rabinow (2013), the main objects of modernist reform in Morocco were industrialization, welfare, and regulation with productivity and efficiency (57-58). And we can certainly observe this as an underlying impetus in Écochard’s approach to regional planning as well, where the development and simultaneous decentralization of industry was to provide the comfort and standard of living that modernist zoning promised. The same applies for the vast neo-Corbusian housing projects that were meant to house the urban workers and rural migrants that took part in this process of regulated industrialization.

Modernization, then, can be defined as the process through which a population can work toward reaching a state modernity (which is perhaps never reachable, precisely because of the need for constant updating of technology). In Moroccan cities, colonialism was the main tool through which, according to Maghraoui (2013), attempted to “transform different forms of hegemonic structures into the domains of science, medicine, technology, urbanism, [and] art” (2) in an attempt, understood by von Osten et al. (2010) as a state of emergency (10), to prepare Morocco to generate the identity of a nation-state and engage in global capitalism (Maghraoui Ibid.). In Casablanca, two devices to give the colony a first push into industrialization were the clock tower, built in 1911 to act “as an indicator that the town […] was therefore expected to function at the same pace as industrial civilization”, and the port, the development which was to facilitate Casablanca’s connection to global economic and intellectual flows (Cohen and Eleb 2002, 43, 125).

Carrières Centrales housing development, as per the Corbusian model of social housing (Cohen and Eleb 2002, 325)

In colonial rhetoric, the Modern was juxtaposed as the opposite of the Traditional. This is directly evident in Lyautey’s commands to separate the villes nouvelles from the “traditional Moroccan city” to experiment with latest best practices in urban and economic planning without negatively impacting Moroccan artistic and social life (Maghraoui 2013, 2, 6; Wright 1991, 85-86). The traditional attaches itself to the concept of supposedly timeless or cyclical continuity, which Wright (1991) contrasts to what I would argue is modernism’s ideological goal of “[perpetual] sudden recent transformation” (88). This, then, is the greatest distinction between the Modern and the Traditional or Postmodern: modernism carries itself on as an unwavering faith in everlasting progress and science as the ultimate and absolute means of improving human quality of life, whereas tradition is posited as a faith in lack of progress or rather a faith in repetition and perhaps its reinterpretation, instead focusing on the value of continuing practices across time. Postmodernism, in reaction to modernism, loses faith in progress and turns to eclectic pastiches and hybridizations of tradition with the cultural outgrowths of modernism.

The modern-traditional dichotomy also necessitates the spatial representation of the temporal hierarchy: traditional being before modernization arrived, and the present being the never-ending arrival of the new and modern. Part of the idea of modernism, after all, is that architecture ought to be deliberately formally ahistorical (even though modernist architecture itself falls victim to tides of artistic style) and establish a hierarchy of modern over pre-modern. According to Wright (1991), this was a simultaneous political and aesthetic goal for Lyautey: modernization and industrial development alongside preservation of specific, sanctioned cultural traditions worked in the interest of stabilizing French colonial control in Morocco (85). Wallenstein (2009; in von Osten 2010) also argued that a formalized system of spatial planning served a dual role of controlling and mobilizing a colonized population as well as claiming to provide them with shelter and better housing (23). As was the case with Prost and even with Le Corbusier in his Plan Obus for Algiers, von Osten derived a framework for understanding the colonial process of appropriation and recycling of the ‘traditional,’ ‘pre-modern,’ and ‘vernacular’: “learning from the vernacular, abstracting it, [and] translating it into aesthetic models” that are then applied back onto the source (23).

At the same time, however, von Osten (2010) suggests that the resulting “colonial modern” broke down the structuralist dichotomy between ‘modern’ and ‘traditional;’ rather, in this system, Europe is no longer the only recipient of modernism, but these ideas instead “move in different directions, circulate, and are renegotiated” (11). The state of this “colonial modern” is also unique in that the forced imposition of modernism also contributed in developing the means for the liberation of former colonies, including Prost and Laprade’s attention to translating pre-modern and traditional building practices into modern equivalents. The ideas the French were implementing in Morocco were subsequently eventually disseminated elsewhere to the world, “entangling” (Ibid., 20) modernism in urban planning and architecture with histories of imperial colonialism.

However, perhaps the greatest twin pitfalls of modernism and modernization in Morocco were: first, the absence of participatory planning; and second, is the political marginalization of urban workers and rural migrants. The lack of native or indigenous participation occurred in spite of the fact that modernist ideas of social equity were foreign and being applied to a very distinct social context from early-twentieth-century Europe. The process of layering two participatory barriers – the professionalization of urbanism alongside cultural differences – generated a group that became excluded from the benefits of administrative reforms and physical engineering of the physical landscape. Because of this exclusion, informality and slumming arise as an economically rational response to the market failure to supply formal housing at a fair price. Von Osten (2010) even proposed that the self-built environment exists “as a means of coping with modern city life” is in itself a form of modernism,” and that beyond concerns of global flows of capital and information, “improvised practices” respond to urban residents’ survival needs better than neoliberal economic policies (21, 30).

Here we are presented with the central irony of modernity: On the one hand, modernism and modernization are supposed to be a form of liberation from the Traditional; they are meant to obliterate supposedly ever-static and non-developing forms of living. But the supposedly liberating state of modernity pushes the “modernized” into a certain captivity as well; after all, the “modernized” become reliant on models established by those who have been modern for the longest, even if there exists an iterative relationship between principles of the colonizers and the modernized-colonized. This is reflected in contemporary policies for slums in Morocco, where the fast pace of slum eradication is creating physical environments that, in continuing on the Corbusian precedent, are not conducive to the continuation of Moroccan urban traditions. Yet at the same time, the forcible local appropriation of these architectural forms (as in von Osten 2010, 33) to create ground-level retail space or divide quarters for subletting, suggests that modernism indeed provides some kind of an emancipatory facility to its recipients. However, if this is the case, then modernism becomes indistinct in temporal hierarchy from traditionalism: there can be no “before” and “after” modernization if both modernity and tradition are means to respond to the necessities of everyday life through individual inventiveness and adaptability as a common denominator between the two. Or perhaps the modernist experience in Morocco merely suggests that the movement failed, and the “before” and “after” pivots itself not around a point of modernization, but one of a flawed drive to change people’s daily lives. In brief, the ironic quality of modernity is that it does not actually distinguish itself from tradition once a population is allowed to control their built environment, and instead of actually providing a new, industrialized way of living, it merely changes the contexts within which tradition is put into practice.

From a post-structuralist standpoint, the dichotomy indeed breaks down as a polarity or even as a spectrum; rather, each informs and is informed by the other, as is the case of Casablanca as well as other cities with significant informal physical landscapes. What responses, then, should be formulated to help policymakers cope with this inherent yet politically repulsive hybridity? After all, if the threat of informality is lack of centralized control, legislators and urbanists should be asking whether housing policies can take advantage of fact that the modernist characteristics of informality do allow for, or perhaps even require, a degree of centralized power, perhaps defined as organized direction of financial and social investments (or even divestments) through flows of capital.

Mismanaged or misdirected efforts at modernization that do not consider the “native production of a modernity” (55) create an environment that I find can be labeled well with the metaphor of Gebirgskriegpolitik (a German neologism that translates as mountain-warfare politics), whereby one side of a group of conflicting political factions impose what is ideologically seen as a natural barrier that must either be protected or overcome, such as the necessitated imposition of modernity, controlled and restricting flows of capital and of resources, or the desire to eradicate informal housing as a generative cell for conflicts (all of which are the case in Casablanca). Following this proposed framework, if policymakers can identify a barrier with the aforementioned characteristics, they can approach the conflict at hand either by imposition of authority (emulating the physical control of a barrier) or by deliberately obliterating the barrier as a source of conflict.

Formalization of the informal processes – which, in a sense, is exactly what Prost and Écochard had originally hoped to do – and imposition of centralized direction and participatory planning can help to uncover and hopefully tame the social systems that generated the violence of 2003 and 2004 that brought more attention to the need to have formal documentation of and planning over the slums that Zemni and Bogaert document as being targeted as locations that foment radical ideologies as well as to alleviate poverty (409-411). However, it is unlikely that the Villes San Bidonvilles, or ‘Cities Without Slums,’ program (Ministère de l’Habitat 2004) will necessarily improve the question of formalization, as these built forms that imitate Écochard since even the early 1980s (as Sebti 2013, 52 described) only continue the imposition of a spatial organizational approach that does not much care for how the system of informal spatial appropriation of can meet people’s needs.

Essentially, then, modernization and modernism have been driving forces in the development of Casablanca, whose urban environment can now be used as a living museum to compare and contrast the effects of modernism as a foreign ideology during colonialism. Yet the city today continues to appropriate modernism to institute a new cycle of tradition which, through the creation of a new cyclical faith in existing means, overpowers the modernist barrier-ideology of the expensively expansive ever-novel. Planning theory can go forward with this in different ways. After all, are we observing the birth of a new and literally post-modern tradition in emerging-economy cities, or is this appropriation a form of tradition generated by modernization? If so, can modernism, then, not modernize? Or has the campaign toward modernization actually succeeded, if paradoxically, by having generated a new tradition? Perhaps all of these are true simultaneously, which is completely plausible, and thus are we confronted with the entangled and further entangling knots of postmodernism.

References

Attia, Kader. “Signs of reappropriation” in Avermaete, Tom, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion von Osten, eds. Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past–Rebellions for the Future. London: Black Dog, 2010.

Barbanente, A., D. Camarda, L. Grassini, and A. Khakee. 2007. “Visioning the Regional Future: Globalization and Regional Transformation of Rabat/Casablanca”. Technological Forecasting & Social Change. 74, no. 6: 763-778.

Cohen, Jean-Louis, and Monique Eleb. Casablanca: colonial myths and architectural ventures. New York: Monacelli Press, 2002.

Eleb, Monique. “The concept of habitat : Écochard in Morocco” in Avermaete, Tom, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion von Osten, eds. Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past–Rebellions for the Future. London: Black Dog, 2010.

International Finance Corporation and The World Bank. “Starting a Business.” Doing Business – Measuring Business Regulations. 2012. <http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploretopics/starting-a-business>

Journady, Kacem. 1999. “Urbanisation et disparités spatiales au Maroc [Urbanization and spatial disparities in Morocco].” Méditerranée. 91, no. 1.2: 93-100.

Maghraoui, Driss. Revisiting the Colonial Past in Morocco. London: Routledge, 2013.

Ministère de l’Habitat, de l’Urbanisme et de la Politique de la Ville [Ministry of Habitat, Urbanism, and Urban Policy]. “Programme Villes sans Bidonville” [Cities Without Slums Program]. 2004. <http://www.mhu.gov.ma/Pages/Habitat/Programme%20Villes%20sans%20bidonvilles.aspx>

Rabinow, Paul. “France in Morocco : technocosmopolitanism and middling modernism” in Driss Maghraoui, ed. Revisiting the Colonial Past in Morocco. London: Routledge, 2013.

Sebti, Abdelahad. “Colonial experience and territorial practices” in Driss Maghraoui, ed. Revisiting the Colonial Past in Morocco. London: Routledge, 2013.

von Osten, Marion. “In colonial modern worlds” in Avermaete, Tom, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion von Osten, eds. Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past–Rebellions for the Future. London: Black Dog, 2010.

Wright, Gwendolyn. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Zemni, Sami, and Koenraad Bogaert. 2011. “Urban Renewal and Social Development in Morocco in an Age of Neoliberal Government”. Review of African Political Economy. 38, no. 129: 403-417.