By Marina Santos

Slums are part of the physical, economic, and social landscapes of many cities. Planners, architects, and governments have created plans and programs, through redevelopment, renewal, and clearance, to address the issues of slum settlements. In Calcutta, during the the 1970s, “basti improvements took a major focus of the government resources…however, [the] self-help concept was not [a] major strand of housing policies advocated” (Sengupta 2010).

Self’-help housing is a bottom-up approach to city building and development. The term (and practice) of “aided self-help” was born in Washington D.C.; however, countries across the world have implemented similar strategies. “Self-help was a reaction to the inadvertent negative outcomes of urban renewal and the loss of confidence and formal planning and architectural orthodoxy” (Ward 2012, 289). It is characterized by individual home-owners’ efforts to rebuild their homes by gradually replacing shack materials with permanent additions, as well as the collaboration between homeowners to improve neighborhood amenities and services with joint resources.

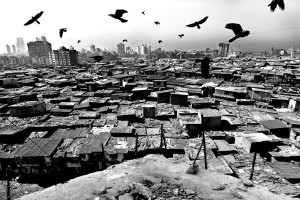

Metropolitan Calcutta is home to 14 million people, with a third of the population living in slums (Ramaswamy n.d.). According to the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Agency (KMDA), the housing need in Calcutta in the year 2000 was estimated to be 70,000 units; however, the average annual building rate was estimated to be only 15,000 to 20,000 units annually (Sengupta 2010). The lack of housing has made housing in the city less affordable and ultimately inaccessible for the urban poor.

The housing policy in Calcutta has shifted from slum improvement from the late 1940s, to slums clearance in the 1950s, to public private partnerships, public rental housing, development of new townships, and neo-liberal housing reforms in recent years (Sengupta 2007). Self-help housing, as a housing policy and an instrument, has received little attention in Calcutta due to concerns about public money being spent with no chance of cost recovery and the lack of replicability (Sengupta 2010). The economics of self-help housing policy is a major hurdle for the Indian government– it has proven unable to provide financial aid, receive tax revenue, and implement nationwide standards for self-help housing.

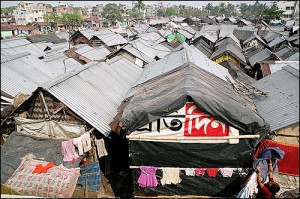

Gorcha & Panditya Bastis in South Calcutta. Home to over 150,000 people and a small-scale recycling industry, these slums will be demolished due to redevelopment initiatives. Souvid Datta.

Promises of Self-Help Housing

Advocates for self-help housing believe that self-help is “an appropriate response by the urban poor to the incapacity of both governments and the formal housing market to provide housing at an affordable price and on a large scale” (Ward 2012). In the case of Calcutta slums, it is a housing policy that the government should consider and support. Through self-help, residents would be able to implement incremental changes to their homes, bettering their homes and lives over time.

Residents are better informed than the government of their immediate needs, and more aware of the intricacies of life in the slums. Therefore, they are better suited to addressing problems facing their homes and neighborhoods than planners, architects, and engineers trying to implement solutions from the outside. Through self-help, slum dwellers can balance their needs and priorities with their resources and capabilities, before implementing the course of action that they desire. The bottom-up approach of self-help housing enables the most disenfranchised to enact the change and the improvements they most need.

Pitfalls of Self-Help Housing

Critics of self-help housing policies argue that self-help glosses over the “some of the high social costs of living and raising a family under conditions of high insecurity, without adequate services, and in poor hazardous dwelling conditions” (Ward 2012). Self-help housing in Calcutta faces these types of challenges. Neither the government nor the slum dwellers have the resources and the funds to create and sustain a self-help housing policy that would pass and abide by social and governmental standards for the quality of a home (Sengupta 2010). The government cannot provide adequate aid, and the slum dwellers themselves cannot afford construction costs and materials. Slums dwellers must first pay for their commute to work, water and electricity, rent, drains and sewers, food, and all other expenses that life entails before they can think about upgrading their homes. Self-help policies require a certain amount of financial assistance; without it, self-help initiatives will fail.

In terms of security, slum dwellers in Calcutta are “illegal occupiers who lack…security and tenure” (Sengupta 2010). The lack of tenure disenchants and discourages slum dwellers from investing in their homes due to the fear of eviction and overall temporary status in the slums. Without tenure, slum dwellers will not have the incentive or desire to improve their lot.

Another potential issue of slum assistance and self-help policy might is that this form of aid might increase migration into the slums, further increasing the housing demand in the city. This migration could also create denser slums and pose new challenges in urban housing and slum settlements.

Self-help housing is a policy and a tool that must be considered in the housing context of Calcutta and cities throughout the world. Like all solutions to complex urban problems, self-help housing has its promises and pitfalls. The bottom-up and localized approach of self-help housing initiatives must be combined with government aid and support in order for self-help to achieve success. Slums are an inevitable part of a city, and it must be accepted that they are here to stay. Instead of demolishing slums, governments and planners must recognize their inevitability and work with the slums. The government can provide the slums with basic and adequate services and let the slum dwellers use their own entrepreneurial skills and self-ingenuity to improve their homes and neighborhoods from the bottom up.

Part II: Slum Upgrading: Basti Improvement Programme

———————————

Works Cited

Ramaswamy, V. “Renewing the City: Efforts to Improve Life in Calcutta’s Urban Slums.” Asia Society. http://asiasociety.org/policy/social-issues/human-rights/renewing-city-efforts-improve-life-calcutta%E2%80%99s-urban-slums (accessed November 17, 2013).

Schenk, W. Collin. “Slum Diversity in Kolkata.” The Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies 1, no. 2 (2010): 91-108.

Sengupta, Urmi. “Housing Reform in Kolkata: Changes and Challenges.” Housing Studies (Routledge) 22, no. 6 (November 2007): 965-979.

Sengupta, Urmi. “The Hindered Self-Help: Housing Policies, Politics, and Poverty in Kolkata, India.” Habitat International 34 (2010): 323-331.

Ward, Peter M. “Self-Help Housing Ideas and Practice in the Americas.” In Planning Ideas That Matter: Livability, Territoriality, Governance and Reflective Practice, edited by Bishwapriya Sanyal, Lawrence J. Vale and D. Christina Rosan, 283-310. Cambridge, 2012.