By Marina Santos

Part I: Self-Help Housing in Calcutta

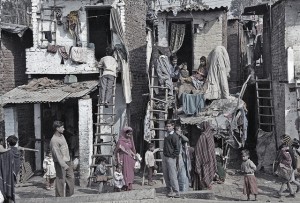

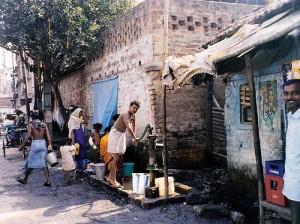

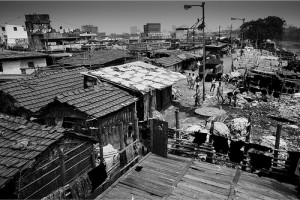

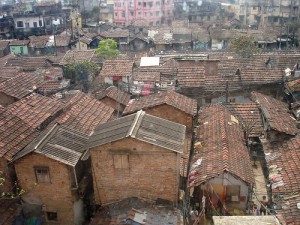

In Calcutta, the term “slum” can refer to both bastis (or bustees) and squatter settlements. Bastis are characterized by huts made of brick, earth, and sticks– usually with tiled roofs. Basti slums are distinct from squatter settlements in that laws against public demolition provide land security and a sense of permanency to residents (Schenk 2010). However, most bastis also have inadequate water, sanitation, and waste disposal services (Ramaswamy n.d.). Due to grave concerns about public safety and health in the slums of Calcutta, a basti upgrading program was established in the early 1970s.

A typical basti settlement, characterized by tiled roofs and brick walls. Galaria d’ Meenakshee, Flickr.

The Basti Improvement Programme (BIP) was introduced in the 1970s by the Calcutta Metropolitan Organization with the urging of the World Health Organization and the support of the Ford Foundation. The primary catalyst for the project was a cholera outbreak that killed hundreds of people in Calcutta slums (Ramaswamy n.d.). The mission was to provide sanitary toilets and drainage systems, implement better waste disposal practices, and construct safer roads with streetlights; moreover, the program concentrated on upgrading, redeveloping, and maintaining existing structures and services in the slums rather than demolishing and rebuilding (Ramaswamy 2008).

An integral part of the BIP was the transferring of tenure rights from private landowners to hut owners. The pre-BIP basti was characterized by a three-tier tenancy system with exploitative landowners at the top of the hierarchy, hut owners one step below the landowners and the rest of the slum dwellers at the bottom. The Thika Tenancy Act of 1981 attempted to remedy landowner cruelty by allowing the government to acquire the basti lands. The removal of the landowners from the hierarchy allowed the hut owners to avoid exploitation and pay the government directly. However, though the hut owners were saved from the landowners, the slum dwellers were not saved from unscrupulous hut owners. Program critics agreed that the “government could not exercise any control over the [hut owners],” a situation that resulted in an increase in rent prices and the “large-scale eviction of poor tenants” (UN Habitat 1993).

The Basti Improvement Programme did succeed in the provision of water and sewage systems, lighting, and roadways. Along with the improvement of public health and welfare the BIP strove “to build a community that could sustain the[se] improvements, and [to devise] a way to overcome the issue of private land” (Schenk 2010). While the BIP succeeded in its goal of upgrading services, it failed in its goal of improving land security, as the BIP and the Thika Tenancy Act “resulted in a sharp rise in bustee rents and land values, and the displacement of bustee-dwellers” (UN Habitat 1993).

Promises of Slum Upgrading

The BIP is an example of a slum upgrading plan that aimed to improve blighted areas by improving services in entire neighborhoods. The promise of a successful outcome were clear: ameliorating basic services and life needs would greatly benefit the basti and basti dwellers. The upgrading of existing infrastructure, which included water circulation and sanitation, storm drainage and electricity, roads and street lamps, would greatly improve the standard of living in the bastis.

Moreover, the BIP aimed to improve public health and welfare without clearing and demolishing the already existing bastis. The hope was that the slums could be made more secure and livable without complete redevelopment. Alternative options, such as slum clearance and relocation, would have been costlier plans that uprooted slum dwellers from their homes. In addition, clearance and relocation often do not work because many slum dwellers feel the need to return to the city where their jobs are located. Redevelopment is an option that improves the physical and health environments of slums; however, most redevelopment schemes involve high-rise developments which do not allow for the entrepreneurial activities that take place in ground-level settlements. The BIP, a slum upgrading scheme, was a pragmatic approach which focused solely on the provision and maintenance of services and security, allowing slum dwellers to stay in their homes while encouraging home maintenance and improvements. Slum upgrading is “not only an affordable alternative to clearance and relocation but it minimizes as well the disturbance to the social and economic life of the community” (The World Bank Group 2001).

Pitfalls of Slum Upgrading

Along with the promises of slum upgrading, the BIP also had its pitfalls. One negative impact of the upgrading of basti settlements was the displacement of former inhabitants. The redevelopment of the slums resulted in higher rent prices for residents. Basti dwellers were low income laborers living on marginal existence, and simply couldn’t afford to stay.

Despite the unsanitary conditions and the welfare concerns that characterize bastis, these slums serve a function to the urban landscape not only in Calcutta but also in many cities throughout the world. These low income settlements provide affordable housing for the urban poor, act as reception centers for urban migrants, provide employment within their neighborhoods, promote entrepreneurial enterprises, and enable mobility through the close proximity of dwellers’ homes and employment opportunities (Rosser 1972). Slums are a natural outcome in the framework of our cities, and slum upgrading is a clear option in improving the living conditions of slum dwellers. Slum upgrading has its promises and pitfalls, but in the end, great care must be given to ensure the well being of slum dwellers. The provision and upgrading of basic needs and services are necessary for these people, but planners must be wary of the resulting eviction and displacement that can be caused by slum upgrading programs like these.

——————————–

Works Cited

Ramaswamy, V. “Basti Redevelopment in Kolkata.” Economic & Political Weekly, September 20, 2008: 35-26.

—. “Renewing the City: Efforts to Improve Life in Calcutta’s Urban Slums.” Asia Society. http://asiasociety.org/policy/social-issues/human-rights/renewing-city-efforts-improve-life-calcutta%E2%80%99s-urban-slums (accessed November 17, 2013).

Rosser, Colin. “Housing and Planned Urban Change The Calcutta Experience.” In The City as Centre of Change in Asia, by Denis John Dwyer, 179-190. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1972.

Schenk, W. Collin. “Slum Diversity in Kolkata.” The Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies 1, no. 2 (2010): 91-108.

The World Bank Group. What is Urban Upgrading? 2001. http://web.mit.edu/urbanupgrading/upgrading/whatis/index.html (accessed November 18, 2013).

UN Habitat, United Nations Centre for Human Settlements. National Trends in Housing Production Practices. Vol. 1. Nairobi, 1993.