Featured image: Players from Team Canada and the Iroquois Nationals during the final game of the 2015 Federation of International Lacrosse World Indoor Lacrosse Championship. Photo courtesy of Darryl Smart.

Lacrosse. A sport played with sticks and a ball. A sport that many Americans wrongly perceive as belonging to upper-class prep school boys. A sport that spread from Indigenous North America to countries around the world (Kolva 2012). In 2015, lacrosse came home: the Federation of International Lacrosse World Indoor Lacrosse Championship (FIL WILC) took place in New York State. Yet despite the location, the United States did not host the championship. Instead, some of the original players of the game did. This year’s host was the Iroquois Nationals, a team representing the Haudenosaunee.

The Haudenosaunee are an Indigenous confederacy in New York State and Canada, more commonly referred to by the outsider name “Iroquois.” We have played lacrosse since before European contact. We would play to resolve conflict, to bond with each other, and to honor the Creator (Kolva 2012). When the Iroquois Nationals put in a bid to host the 2015 WILC, they did not expect the championship to choose them as the host (Jemison 2015). The championship was centered at the Onondaga Nation’s reservation because it serves as the capital for the six nations that make up the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Hosting the WILC served as a great opportunity for the Haudenosaunee to assert our sovereignty and to construct a new community center, and we were able to do so while avoiding the complications often associated with hosting large sporting events because of the unique dynamics of hosting on a Native American reservation. On the other hand, some Onondaga community members and leaders took issue with the exorbitant spending, arguing that spending to improve housing or to improve cultural and language revitalization programs should be a priority (Jemison 2015). The 2015 WILC is a great example of strong, successful Indigenous planning, a topic which the literature too often overlooks.

Members of various Haudenosaunee communities danced and shared the Creation Story at the opening ceremonies. Photo courtesy of Bailee Hopkins.

In order to understand the planning process and the significance of the championship, I spoke with Ansley Jemison, the executive director of the Iroquois Nationals. He explained that the championship centered on the Onondaga Reservation, and the Iroquois Nationals’ staff oversaw the planning efforts while working with the Onondaga Nation. The Iroquois Nationals were responsible for hiring Honeysweet Productions, a company that helps plan events. This included deciding what will happen, who to hire, and what kind of equipment and infrastructure is necessary. For this championship, Honeysweet Productions helped create a temporary site for vendors and events in the center of the reservation. This was done by using tents (“Event Schedule” 2015).

Immunity to the “Mega-Event Syndrome”

The use of temporary structures is one way in which the 2015 WILC avoided what Müller has termed “the mega-event syndrome” (Müller 2015: 6). The mega-event syndrome occurs when mega-events—often sporting tournaments—cause more damage than good to the host community (Müller 2015). One potential remedy that he proposes is to create temporary structures if it is unclear whether permanent structures would be reused or maintained following the event (Müller 2015). In the case of the 2015 WILC, the Onondaga saw no need to invest money in creating permanent structures designed for vendors and events since such construction is not currently in demand. The Iroquois Nationals were likely able to avoid the mega-event syndrome because of the small size of the Onondaga Nation. They did not have to go through multiple levels of government in order to plan the championship, which would have made the process more complicated and would have posed the risk of inefficient use of resources (Müller 2015). Their one big project—an indoor lacrosse arena—had a purpose in mind for after the championship, which is one of Müller’s suggestions to make mega-events more efficient. Lastly, the championship was not centralized in the sense that not all of its events took place in one area. Games were played in four arenas, two of which were on the Onondaga Reservation and two of which were in Syracuse. This is beneficial in preventing the mega-event syndrome because it reduces traffic to one area (and thus, new transportation infrastructure is less necessary), and because it prevents a concentration of same-use stadia in one location, where they are not likely to be used after the championship (Müller 2015). Problems such as gentrification following the event—for example, people being relocated so that the area around the event becomes a wealthy district—seem irrelevant because other than the arena, nothing new was constructed, and the arena is not likely to draw in new residents or businesses. The 2015 WILC is a good model of a sporting event that avoided creating many of the problems associated with similar events. Build small, build temporary, and use what already exists: these are the lessons from the 2015 WILC’s built environment. In contrast, Brazil built, remodeled, and rebuilt 12 stadia for the 2014 FIFA World Cup, many of which are now either unused or underused. Hosting the FIFA World Cup had a price tag between $11 billion and $14 billion, which is unfortunate when Brazil’s hospitals and schools would benefit from more funding. Between 250,000 and 1.5 million people had to relocate due to the new construction, usually without compensation. From a planning standpoint, Brazil’s expenditures were not worthwhile in the long run because they further deepened inequality in the country and will not generate revenue in the long run (Mitra 2015).

Was it Worth the Price?

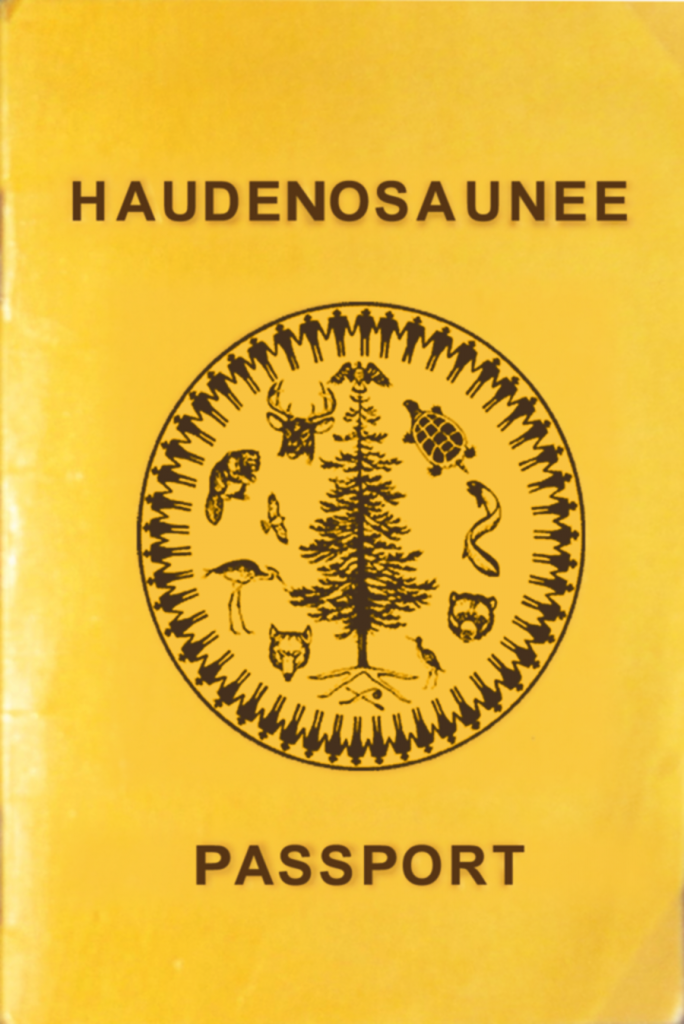

Unfortunately, like Brazil, one issue that the Iroquois Nationals could not avoid was the expense. Ansley heaved a sigh as he told me that the championship cost $10.5 million. On the one hand, that $10.5 million was an investment. It allowed the championship to take place on the sport’s homelands. This is inherently an act of asserting sovereignty because lacrosse originated in Indigenous lands now occupied by a sovereign nation within a nation. Too often, Americans forget that Native peoples have their own governments, their own policies, and federal recognition of their sovereignty. The fact that the Haudenosaunee hosted an international event reinforces that the Haudenosaunee are their own nations separate from the U.S. (Jemison 2015). They even stamped the passports of all team members from other countries as they entered Onondaga territory (Moses 2015). This was a major affirmation of sovereignty considering what happened to the creators of lacrosse when they went to England for the 2010 WILC. Upon arriving in England, the Iroquois Nationals were denied entry due to their Haudenosaunee passports, which were deemed inadequate (Alfonso 2010). The team was barred from their own game because they used their own passports instead of American and Canadian passports. This in itself seemed like England—one of the countries that colonized the Americas and damaged Native lifestyles—was once more denying Native sovereignty. By having their own passports, the Haudenosaunee are reaffirming that they are their own nation separate from the U.S. and Canada. Fortunately, the issue seems to have been primarily one of technology. The British said that the passports didn’t meet encryption standards. However, the U.S. didn’t say whether they would let the Haudenosaunee back into the country on their passports following this conflict because they neither wanted to recognize the passports’ validity nor overtly ignore that the Haudenosaunee have a stronger claim to American soil than mainstream Americans (Hill 2015). An international lacrosse tournament managed to cause a huge debate about Indigenous sovereignty.

The cover of the Haudenosaunee passport, which has been met with controversy when Haudenosaunee people attempt to travel abroad.

Source: Matthew G. Bisanz on Wikimedia Commons

From a physical standpoint, the money created a new arena, which is now being converted into a community center. This is a great investment because the community center will bring people together, thus strengthening social ties, as well as provide a fitness center to promote good health. Jemison sees this as an investment for the youth because they are the ones who will reap the benefits. They will have a center where they can continue to learn about their culture, where they can interact with others, and where they can maintain good health.

On the other hand, many community members and leaders argued that the money spent on the tournament could have been spent on other projects. They reasoned that if the Onondaga Nation, with contributions from the Seneca Nation and private donors, could raise $10.5 million, they could have raised that money sooner and used it to improve living conditions on the reservation (Jemison 2015). Ansley mentioned that homes for the elderly are lacking, and he feels conflicted about whether the benefits to sovereignty and the creation of the community center were worth it when there are Haudenosaunee people who would benefit from more investment in housing and infrastructure. Other uses for the money suggested by the community were cultural revitalization and language revitalization programs (Jemison 2015).

In the end, no money was diverted to improve housing or infrastructure, nor to fund revitalization programs (Jemison 2015). Citizen participation seems to have been at a level of “placation” on Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation, which means that planners and other officials listened to all voices without guaranteeing that their desires would be fulfilled (Arnstein 1969). Davidoff, the planner who came up with the idea of advocacy planning, would probably argue that this is improper and that the planners—in this case, the Iroquois Nationals and the Onondaga Nation—should have listened more to the community so that the community as a whole would be better off. Ideally, the planners would have proposed multiple concepts for the championship and then chosen the plan with the most community support (Davidoff 2012). If the Iroquois Nationals had drafted a plan that included making improvements to housing, for example, and the residents of the Onondaga Reservation preferred this plan over the plan that was actually adopted, then hosting the WILC would have had more lasting benefits. Even from the perspective of the Iroquois Nationals, improvements to the Onondaga Reservation would be beneficial because some members have connections to that reservation, it would show gratitude toward the Onondaga for allowing the championship, and it would strengthen the community in the eyes of the international guests. Planning for a sports tournament has the potential to improve the community, so why not distribute the money accordingly?

A Unique Construction Process

That is not to say, however, that hosting the WILC was a poor use of money. As mentioned earlier, the new lacrosse arena, which the Onondaga Nation spent $6.5 million on, will serve as a community center. The current Onondaga Nation Arena is fully utilized at times, so having another facility for community and sporting events will be beneficial to the Onondaga. Because its design reflects local knowledge and culture, its future use is not the only positive aspect. Named Tsha’ Thoñ’nhes, which means “where they play ball” in Onondaga, the arena resembles a longhouse, the type of buildings traditionally used by the Haudenosaunee. The architect and project manager are both members of the Onondaga Nation, and they wanted to incorporate Haudenosaunee principles in their design. This is why they used natural construction materials such as wood and stone (Moses 2015). After all, longhouses would be constructed out of wood, not a building material such as concrete or plaster.

Using local knowledge as a fundamental part of the planning process often leads to social and environmental justice and resilient communities since even often-marginalized voices are incorporated into the planning vision (Innes and Booher 2010). In this case, local knowledge created a community center that will preserve community bonds and culture. The social impacts of using local knowledge in the design of this arena is that it serves as a reminder that the Haudenosaunee have their own architecture and their own beliefs about natural resources that are unique from the mainstream American view. Because the professionals are a part of the local community, one can argue that the arena was designed by the community, for the community.

Tsha’ Thoñ’nhes, the new lacrosse arena built for the 2015 WILC. The building, which is long and narrow, made of wood, and has skylights reminiscent of smoke holes, resembles a longhouse. Photo courtesy of the Onondaga Nation.

Source: @OnondagaNation on Twitter

The actual process of approving and constructing the arena is interesting because of its short time frame. Discussions began at the beginning of 2015, and construction took less than five months. This is because the planning process on reservations is subjected to different rules. Otey Marshall, the project manager for the construction company in charge of the arena, said that such a project would have taken twice as long if it were being built off of reservation land. However, because the Onondaga Nation has independent control over its land, and because they provided most of the funding, the planning process did not have to go through reviews by multiple government boards (Moses 2015). This was efficient for the Iroquois Nationals, but one wonders about the importance of the bureaucratic review process that the United States faces. Is this review process efficient and worthwhile, or does it just slow down and complicate the planning process? Could this arena potentially have problems that a government agency would have caught?

The fact that the Onondaga Nation does not need any U.S. approval (federal, state, or local) reflects that they are a sovereign nation. In the past, Native nations have struggled to retain control over their land as federal policies limited their autonomy and made them dependent on the government for development (Zaferatos 1998). In this instance, it seems that federal policies of stepping back to allow self-governance were effective because the Onondaga Nation could easily construct a community center that reflects their needs, without dealing with the bureaucracy of another nation.

That’s Great, But What’s the Bigger Picture?

Examining the planning process and lasting impacts of the 2015 WILC reveals that Native nations can assert their sovereignty and plan with their community’s unique needs in mind. The planning process differs from the planning process that most American cities use because Native nations are independent. Planning literature tends to neglect planning processes that take place on Native American reservations and in Native American communities, despite the uniqueness and significance of these processes. Native Americans are among the most underrepresented group in planning processes within the borders of the U.S., which is in part responsible for the underdevelopment of many Native communities. Effective planning by Native American communities takes into consideration the nation’s history and past experiences while incorporating objectives that further Native claims to sovereignty (Zaferatos 1998). The Onondaga Nation’s planning efforts are successful in this aspect because they used culture and past denials of sovereignty (i.e., the passport dilemma) in order to create an event that strengthens the community as one emancipated from U.S. control.

Zaferatos argues that another way for Native nations to gain representation in the planning field is through participating in planning actions taken by non-Native governments. This way, Native nations can make claims to the land and advance their own goals by gaining power and rights from the outside (Zaferatos 1998). In a way, the Iroquois Nationals did this by partnering with Syracuse to host the lacrosse matches. They were able to use unseated Onondaga land for the championship by collaborating with a non-Native government, which serves as a reminder that Syracuse was once Onondaga territory (Jemison 2015).

Often, non-Native governments do not take Native voices into consideration; they ignore local knowledge. Innes and Booher developed three reasons why local knowledge is ignored, all of which are relevant to Native voices in the mainstream. These are epistemological anxiety, which results from discomfort with ways of thinking outside of the mainstream; anxiety about difference in the way one looks, acts, speaks, or in values; and anxiety about uncertainty because Western thought is grounded in certainty and absoluteness, while others may understand that change and development are natural and inevitable (Innes and Booher 2010).

If planners became more comfortable with Indigenous ways of thinking, which are often rooted in place, they are likely to find solutions to make cities more sustainable in the long run and to make cities more socially equitable. As the 2015 WILC demonstrates, Native Americans are capable of planning in a sustainable manner. In the future, planners will hopefully incorporate Native voices when planning the American communities seated on their homelands. After all, if Natives can plan sustainably for themselves, they can surely help other communities on their homelands with their planning endeavors.

The Iroquois Nationals team waves their flag, which is a cloth representation of what was originally a wampum belt representing the original five nations constituting the Haudenosaunee Confederation. Behind the flagbearers march two players holding the Two-Row Wampum Belt, which is a treaty between the Haudenosaunee and all settlers, promising a policy of peaceful coexistence. Photo courtesy of Fredrick Blaisdell.

Source: @FredBlaisdell on Instagram

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend a huge nya:weh to Ansley Jemison for giving up an hour of his time to discuss the WILC with me, as well as for providing me with photos taken by Darryl Smart. I can’t thank him enough! I would also like to thank the Onondaga Nation, Bailee Hopkins, and Fredrick Blaisdell for giving me permission to use their photos in this article. Finally, I would like to thank Professor Minner, Raquel Blandon, and Victoria Neenan for their feedback on this article!

Works Cited

Alfonso, Fernando, III. “Passport Dispute Halts Iroquois Lacrosse Team’s Trip to World Competition in England.” Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group, 10 July 2010. Web. 11 Nov. 2015.

Arnstein, Sherry R. “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35.4 (1969): 216-24. Taylor & Francis. Web. 10 Nov. 2015.

Davidoff, Paul. “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning.” Readings in Planning Theory. Ed. Susan F. Fainstein and Scott Campbell. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2012. 191-206. Print.

“Event Schedule.” FIL World Indoor Lacrosse Championship 2015. WILC 2015, 2015. Web. 11 Nov. 2015.

Hill, Sid. “My Six Nation Haudenosaunee Passport is Not a ‘Fantasy Document.’” The Guardian. Guardian Media Group, 30 October 2015. Web. 25 November 2015.

Innes, Judith E., and David E. Booher. “Using Local Knowledge for Justice and Resilience.” Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. New York: Routledge, 2010. 170-95. Print.

Jemison, Ansley. “Behind the Scenes of the 2015 World Indoor Lacrosse Championship.” Personal interview. 10 Nov. 2015.

Kolva, Brian. “Lacrosse Players, Not Terrorists: The Effects of the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative on Native American International Travel and Sovereignty.” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 40 (2012): 307+. Business Insights: Essentials. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Mitra, Arjyo. “An Ethical Analysis of the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil.” Law and Business Review of the Americas21.1 (2015): 3-19. ProQuest. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

Müller, Martin. “The Mega-Event Syndrome: Why So Much Goes Wrong in Mega-Event Planning and What to Do About It.” Journal of the American Planning Association 81.1 (2015): 6-17. Taylor & Francis. Web. 10 Nov. 2015.

Moses, Sarah. “Onondaga Nation Builds $6.5M Arena in Record Time for Lacrosse Championship.” Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group, 11 Sept. 2015. Web. 10 Nov. 2015.

Smart, Darryl. Lyle Drives. 2015. N.p. By Iroquois Nationals.

Zaferatos, Nicholas Christos. “Planning the Native American Tribal Community: Understanding the Basis of Power Controlling the Reservation Territory.” Journal of the American Planning Association 64.4 (1998): 395-410. Taylor & Francis. Web. 11 Nov. 2015.