Got ticks on your mind? Your questions. Our answers:

How common are tick-borne diseases — and who is at risk?

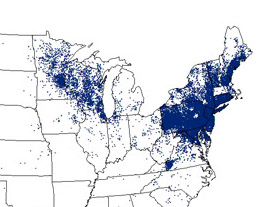

Lyme disease is the second most common infectious disease in the entire U.S. But over 96% of all cases come from only 14 states. Now that’s scary, because New York and the Northeast are at dead center for tick trickery.

Indeed, Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the entire United States — and the second disease most commonly reported to the Centers of Disease Control, aka the CDC. (It comes right after chlamydia and before gonorrhea—both sexually transmitted diseases that could strike most anywhere.)

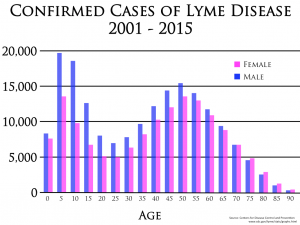

Each year, the CDC gets reports of about 30,000 cases of Lyme disease. But most likely that’s just a fraction of the number of cases. The CDC estimates that each year between 300,000 and 400,000 people are infected with the bacteria causing Lyme — and children ages 5 to 9 have the greatest risk. Parents, check your kids for ticks every day. Make it as mandatory as brushing teeth. “Oh, they were outside for only 10 minutes” or “Oh, but we live in a big city. How could there ticks possibly be here?” — trust us, these aren’t reasons to skip.

No, you don’t have to be an outdoor adventurer to be exposed to disease. People can chance upon ticks in all sorts of places. Pushing a friend on the swings, gardening, picnicking at the park, taking a shortcut through a vacant lot, raking leaves—any perfectly normal activity could put you or your kids on the wrong side of a tick.

What diseases do ticks transmit?

Lyme disease is hardly the only pathogen ticks carry. They can also carry anaplasmosis, babesiosis, erhrlichiosis, Powassan virus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, and Borrelia miyamotoi—a bacteria related to the agent of Lyme disease. (More info: Lyme Disease by the Numbers.)

Naturally, different kinds of ticks transmit different disease-causing pathogens — and the list of tick-borne pathogens continues to grow. Plus ticks can transmit more than one pathogen at a time. Example? The blacklegged tick (aka the deer tick) can transmit Lyme disease, anaplasmosis and babesiosis all at once. Here’s the short list:

- Blacklegged tick: Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus

- Lone star tick: ehrlichiosis, southern tick associated rash illness (STARI), tularemia

- American dog tick: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia

Does every tick convey disease-causing pathogens?

No. Ticks don’t share a common destiny. Not every tick carries the pathogens that make us sick. Here in the Northeast, three ticks transmit pathogens—the blacklegged, lone star and American dog ticks.

Larval ticks, the stage that hatches from eggs with only six legs (nymphs and adults have eight legs), aren’t thought to play a major role in disease. But if larval ticks take their first blood meal from an infected animal, well—they’re infected too. Once they morph into nymphs, they can transmit whatever pathogens they took on.

Note: it’s possible that Powassan virus, carried by the blacklegged tick, can be transmitted from a female to her offspring — and that larval blacklegged ticks can transmit Borrelia miyamotoi, a type of relapsing disease. And what’s a relapsing disease? It’s when signs and symptoms of disease return after it seemed the disease was gone.

Blacklegged nymphs cause the most disease—partly because

- they’re roughly the size of a poppy seed—not easy to see, and …

- they’re active in spring when people aren’t thinking about ticks — though it’ll be summer before symptoms show.

Some nymphs and adults never acquire pathogens. Not every tick is infected. The rate of infection differs throughout the region. No common destiny there.

If I find a tick crawling on me, am I at risk for disease? And … how do they transmit disease?

Ticks transmit pathogens only while they’re attached and feeding. So no, a tick can’t infect you while it’s still looking for a place to feed. Once it’s fed, it’ll drop right off. That said:

- if you find a tick crawling on you, don’t squish it

- brushing ticks off your clothing is no guarantee they’ll stay off.

But if you keep a small vial of rubbing alcohol in your backpack or bag, you can quickly kill ticks by dropping them in. And that’s one less tick in your neck of the woods.

How do they make you sick? Ticks pick up pathogens from one organism (make that the mouse rummaging around under the shrubbery) and transmit them to another (make this one your kid). Here, not for the faint of heart, is how it works:

Larval ticks slide their mouthparts into the mouse — their soon-to-be host — and begin sucking blood. (Those mouthparts might seem a poor excuse for a head, but they get the job done.) At the same time, their saliva enters that mouse’s bloodstream — and yes, the saliva might be carrying pathogens. The time required for pathogens to pass from tick to host is variable. While viruses such as Powassan virus can be transferred within minutes, bacteria appear to take longer. (Just how long is open to debate, so we won’t get involved in that one.)

Need to remove a tick? Learn how here: Its tick season. Put away the matches.

We’ve got a couple of other posts in the pipeline, so we won’t return to this riveting topic until early or mid-July. But do stay tuned.