“The blending of the natural world into one great monoculture of the most aggressive species is … a blow to the spirit and beauty of the natural world.”

— Bruce Babbitt, former Secretary of the Interior

The year was 1997. I’ll tell you right off what our tally was. Of white pine, red oak, and slippery elm, one each. Two each of basswood, big tooth aspen, hop hornbeam, beech, and sugar maple. Four, five, and six respectively of witch hazel, hemlock, and black cherry. Eight black walnuts. Ten white ash. Fourteen chestnut oaks.

Those 14 tree species were the natives, and together they stood 60 strong.

Now for the other three — the invaders. Crowding the sunny verge along the walk, a couple dozen buckthorns. In one section of woods at least 50 seedling ailanthus, commonly known as tree of heaven.

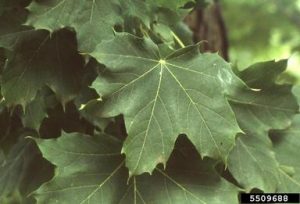

And scattered throughout, 238 Norway maples.

What’s the context? I had asked Robert Wesley, botanist and Natural Areas Manager at Cornell Plantations (as it was then named*), to walk with me through Fall Creek Gorge in the City of Ithaca, checking for invasive non-native tree species. We met at a suspension bridge that spans the gorge, where a casual look a few months before had inclined me to think that green and inviting as the gorge seemed, something might be amiss.

And it was. True, our count was informal. Most of the Norways were saplings; many won’t make it to adulthood. But even now — for an undisturbed forest, six to one is not your usual ratio of “exotic aliens” (as these invasives are often called) to native tree species. After all, this was no vacant town lot, where you’d expect urban trees to seed in. And while the slope near the top may once have been open pasture, Wesley thinks it’s unlikely that the gorge itself was ever logged, creating openings for opportunistic tree species.

“It’s just too steep for logging,” he says. “Most likely these exotics — especially the Norway maples — came to dominate here because their canopies are so dense that they shade out the young of every other tree in the forest.” Those 14 gorgeous chestnut oaks, for example — big mothers all — represent the last of their kind in that place. We didn’t see a single seedling.

After habitat loss, invasive species are the greatest threat to biodiversity in North America. For in addition to whatever particular biological advantage each invasive species enjoys by nature, collectively they benefit from one added advantage: most of the predatory organisms that kept them in check in their home ecosystems — in Europe, say, or Asia — didn’t come over with them.

At the time this was written in 1997, data from the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management indicated that every day another thousand acres (perhaps as many as 4,500) of open land succumbs to nasty non-native weeds.

How has this happened?

Well, take me, for example. Ten years of intensive gardening from 1987 – 1997 (I’m talking a 1,000-plant plus backyard Eden) I inadvertently introduced at least 10 lovely but invasive plants to my property. Most I eradicated as soon as I knew my error, but one may have proved beyond diligence. A couple more continue to push the bounds. Come a year when I get tired, I can easily imagine the garden as the epicenter of an altered local ecosystem.

Indeed, plant collecting — that delightful Victorian occupation — is hardly passé. Every year dozens of professional and amateur enthusiasts scour still-remote regions of the planet, searching out the rarest, the most stunning, and the truly bizarre for a burgeoning domestic market newly keyed in to novelty. As I was, not that long ago.

Of course, big as it is, the nursery industry accounts for only a fraction of the potential for loss. Still, our gardening and landscaping habits provide a great jumping-off point for a conservation ethic that weds theory and practice.

“Informing ourselves is key,” says Wesley. “We shouldn’t fall prey to every enticing ad we see. If we’ve got nuisance plants in our gardens, we should dig them out, but we shouldn’t then dump them in the woods or along the roadside. Or if we dig up pretty flowers from the roadside, we’d best know what they are first, and did they get where they are because they’re invasive?

“And I don’t think anyone should plant a Norway maple — but if they do, they should place it far from hedges or woodlots where it could easily seed in. In the middle of a wide lawn that will be carefully mowed for the next three hundred years or so would be ideal.”

Invasives are everywhere. What can we do about it? NYS IPM’s invasive species conference on July 17 brings together a wide range of speakers to address the scope of the problem. Join us. Also check out NYSIPM’s publications on invasive species at home or on the farm. Most county Cooperative Extension offices also provide information on invasives. Look them up online.

*Cornell Plantations has a new moniker: Cornell Botanic Gardens — learn how they cope with invasive species.

Originally published in the Finger Lakes Land Trust newsletter.