I’m an urban entomologist with expertise in pest management, so you might think my house is free from pests. Not true. My recent adventure confirmed the importance of addressing an issue at the onset. Otherwise, things can get pretty ugly.

The Situation

A small portion of my basement is a dirt floor crawl space. When I moved in (August 2014) it was clear that this was not only a raccoon latrine, but mice had been nesting in the insulation above, so the dirt floor was covered in droppings and old cached food items. I sealed the exterior foundation from future intrusion and installed 5-mil thick plastic over the soil to reduce moisture and provide a good surface to crawl on for other projects that needed my attention.

My Mistake

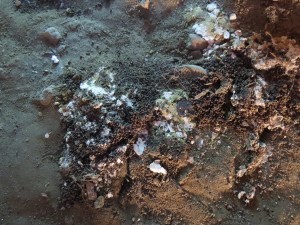

In the fall of 2015 I noticed a few meal moths (Pyralis farinalis) fluttering around the basement, which seemed pretty odd. Something made me look under the plastic and I saw that where there had been organic matter was now mold. Caterpillars were feeding in this area on the organic debris, leaving behind their pellet-shaped frass and head capsules. (Frass is caterpillar poop.)

And head capsule? Remember that caterpillar skin doesn’t grow along with the caterpillar. It needs to molt as it grows. The first thing it sheds is the skin around its head — the head capsule.

But back to my story. I decided that the mold was probably a bigger concern than the moths, so I kept the plastic down and decided I’d tackle the issue later.

Beginning this spring, the number of moths in the basement rose steadily. When it warmed up, I decided to open the windows, pull up the plastic, and dry out the soil. Big mistake. For every moth flying around, there were a dozen more under the plastic. I had unleashed a blizzard of insects. Entomologist dream come true? Nope, not really.

What I Did

I removed moths from the walls with a handheld vacuum. Meanwhile I noticed two things about them:

- they aggregate in certain areas, likely due to the presence of a female emitting pheromones

- they’re negatively phototactic; they avoid light

This meant I could crawl in my dimly lit space to suck up dozens of meal moths at a time, reducing mating opportunities. Wearing the right gear — a HEPA mask, goggles and gloves — I turned the soil, opened the windows and used a box fan to keep the space dry. Even if more adults emerged (which they did), the larval food source was eliminated, preventing more breeding.

What I Should Have Done

As soon as I saw the first moth and found the source, I should have addressed the issue – the breeding material. The ideal solution was (and is) to remove the contaminated soil that holds frass and other organic material, then take it outdoors where it will degrade over time. Covering up a problem doesn’t make it go away but makes it worse.

The Lesson

If you come across a pest problem, attend to it right away. Identify and remove sources of food, especially breeding sites. It is much easier to deal with a small, confined population than a large dispersed one.