J.M.Iacchei Cornell University Library curators build our rare and distinctive collections to enhance strengths, expand subject areas, and respond to instruction and research needs. Laurent Ferri, curator of pre-1800 collections, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Kroch Library, has had a long scholarly and personal interest in Japan and the equine subject area. He has added a few important equine manuals and scrolls to the collection, which complement Cornell’s equine strengths, like the Cornell Vet School, Equine Hospital, and Equine Park. For example, Laurent recently acquired this Japanese equestrian arts scroll from a family of New York-based booksellers. Assessing, stabilizing, and rehousing new acquisitions are a priority area of responsibility for the Conservation Lab so new collection items can be safely made available for use, instruction, and research.

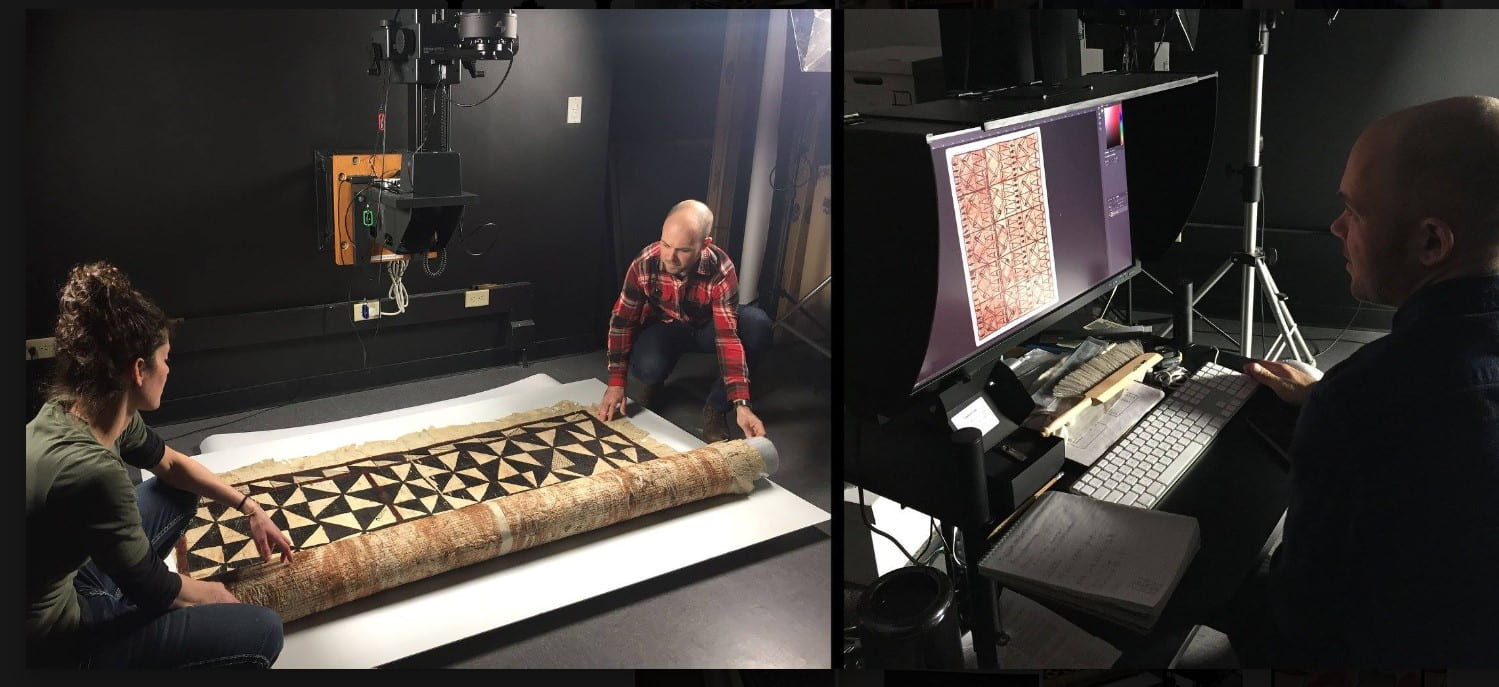

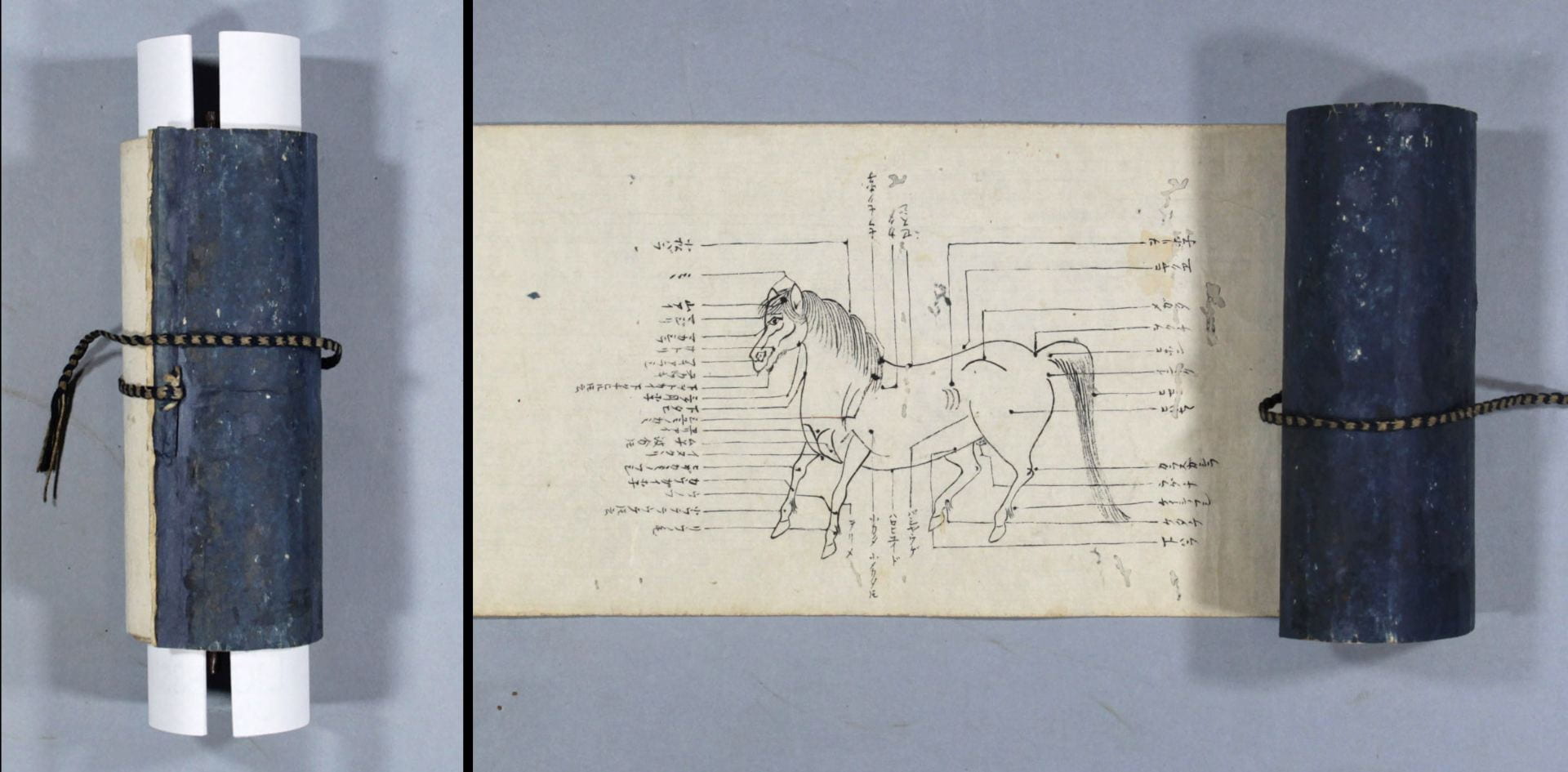

Cornell University Library curators build our rare and distinctive collections to enhance strengths, expand subject areas, and respond to instruction and research needs. Laurent Ferri, curator of pre-1800 collections, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Kroch Library, has had a long scholarly and personal interest in Japan and the equine subject area. He has added a few important equine manuals and scrolls to the collection, which complement Cornell’s equine strengths, like the Cornell Vet School, Equine Hospital, and Equine Park. For example, Laurent recently acquired this Japanese equestrian arts scroll from a family of New York-based booksellers. Assessing, stabilizing, and rehousing new acquisitions are a priority area of responsibility for the Conservation Lab so new collection items can be safely made available for use, instruction, and research.

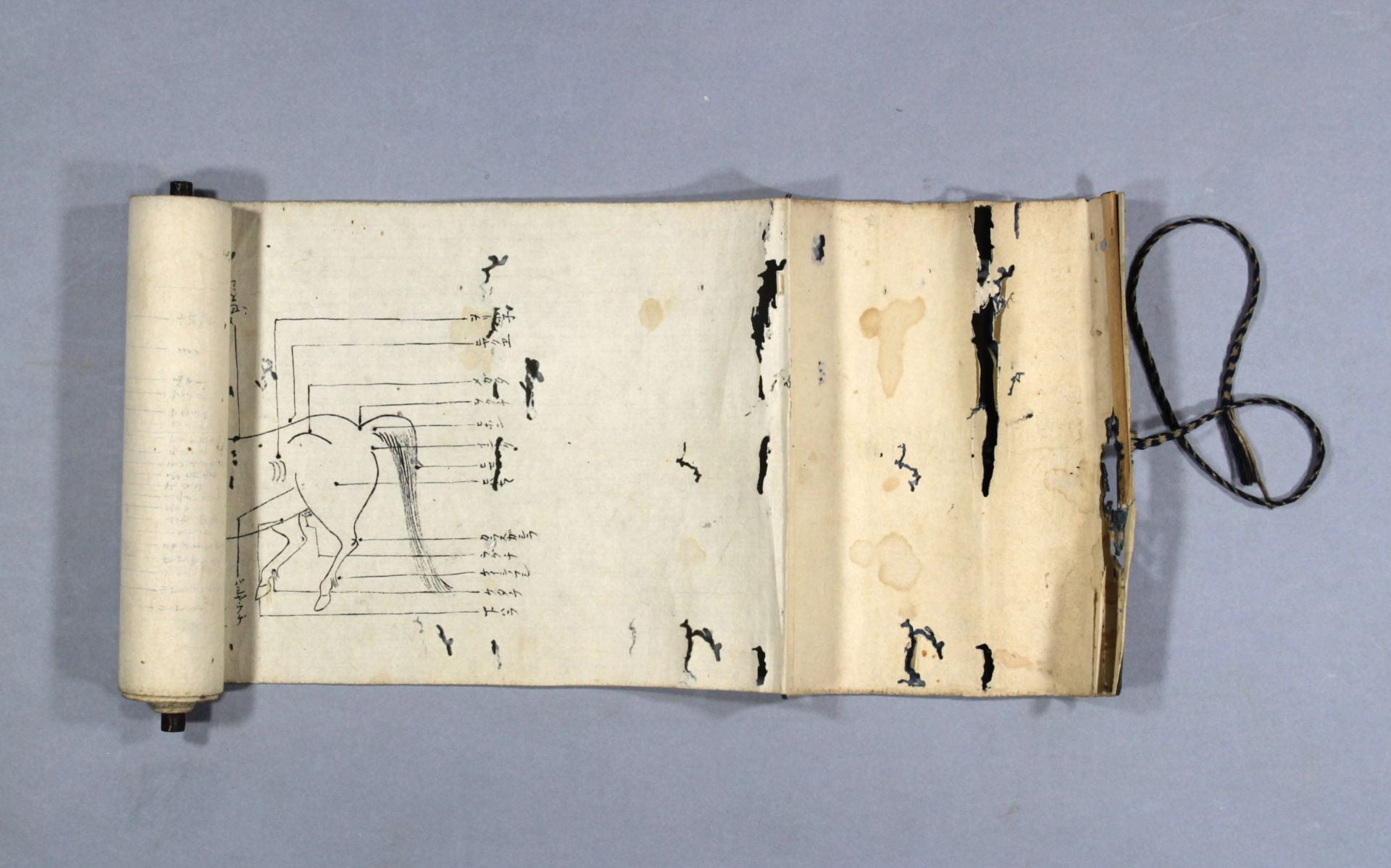

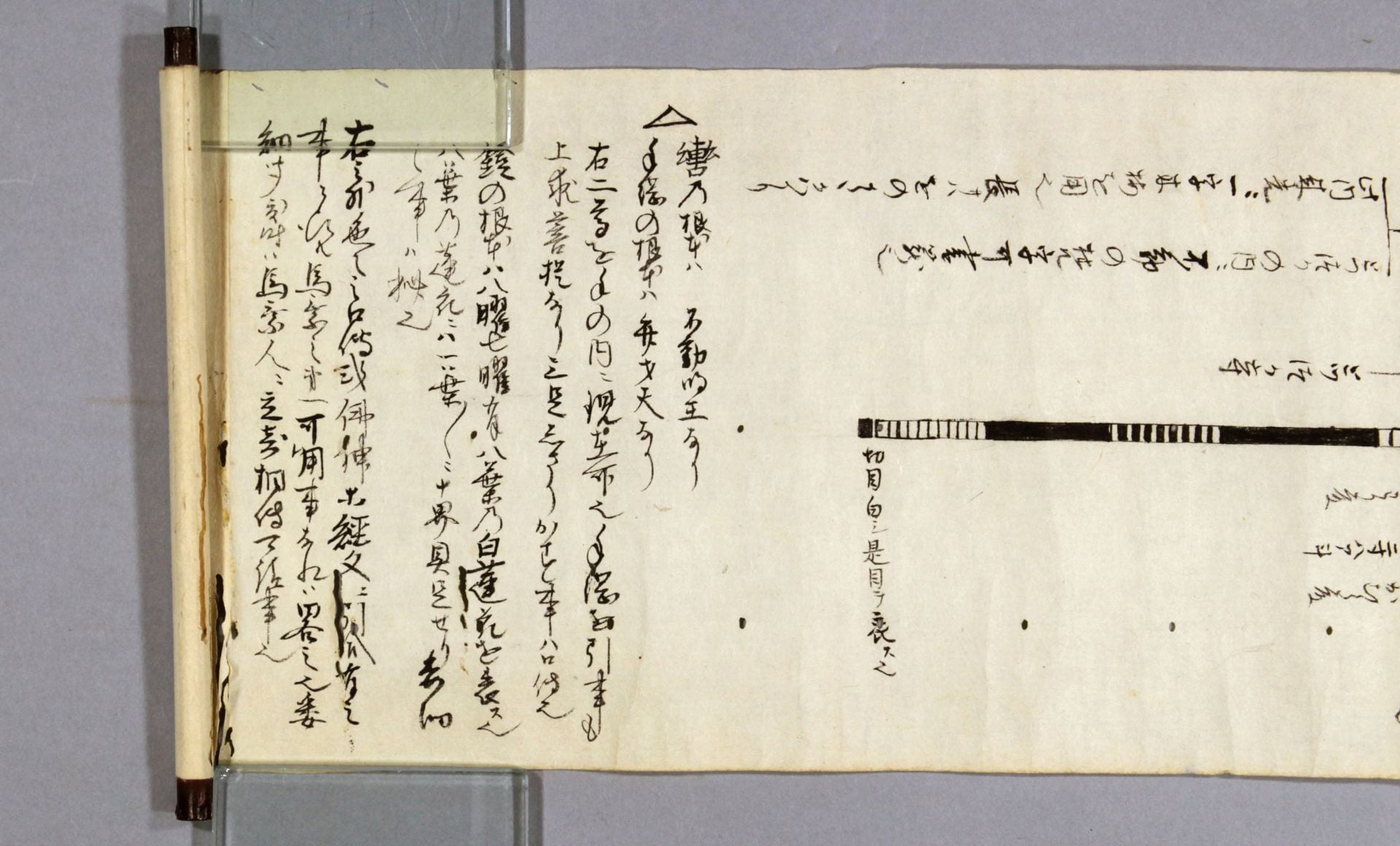

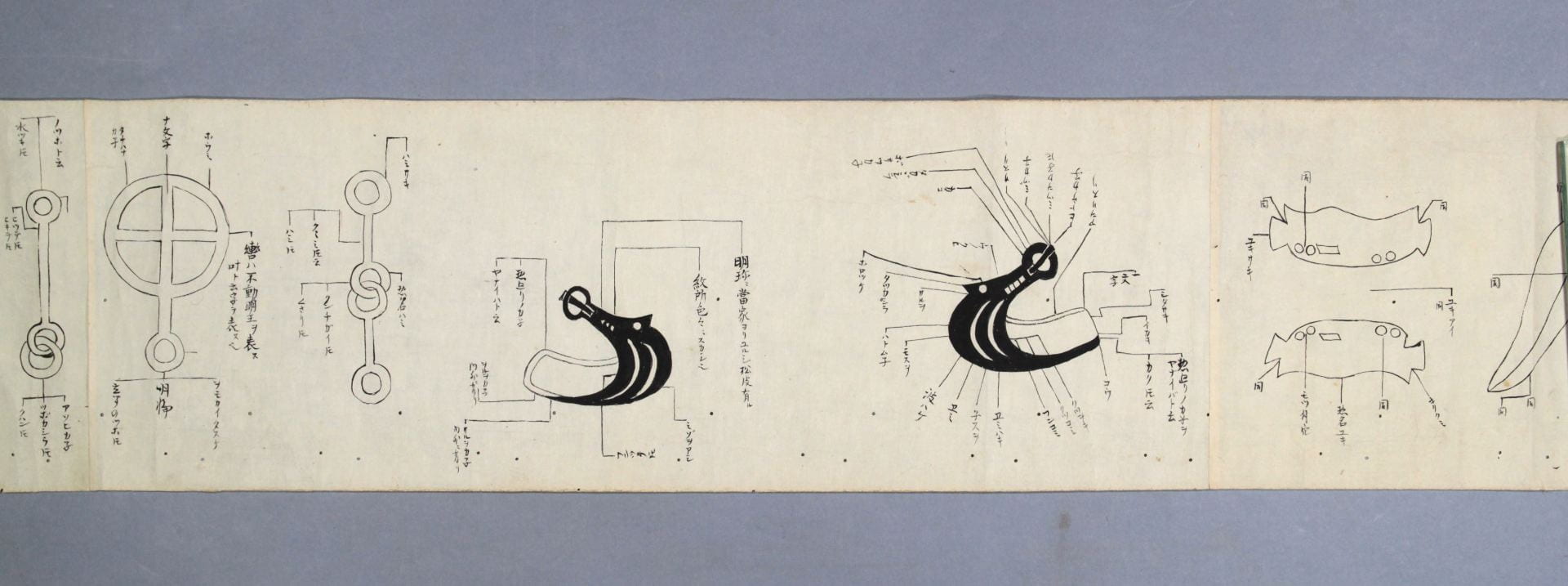

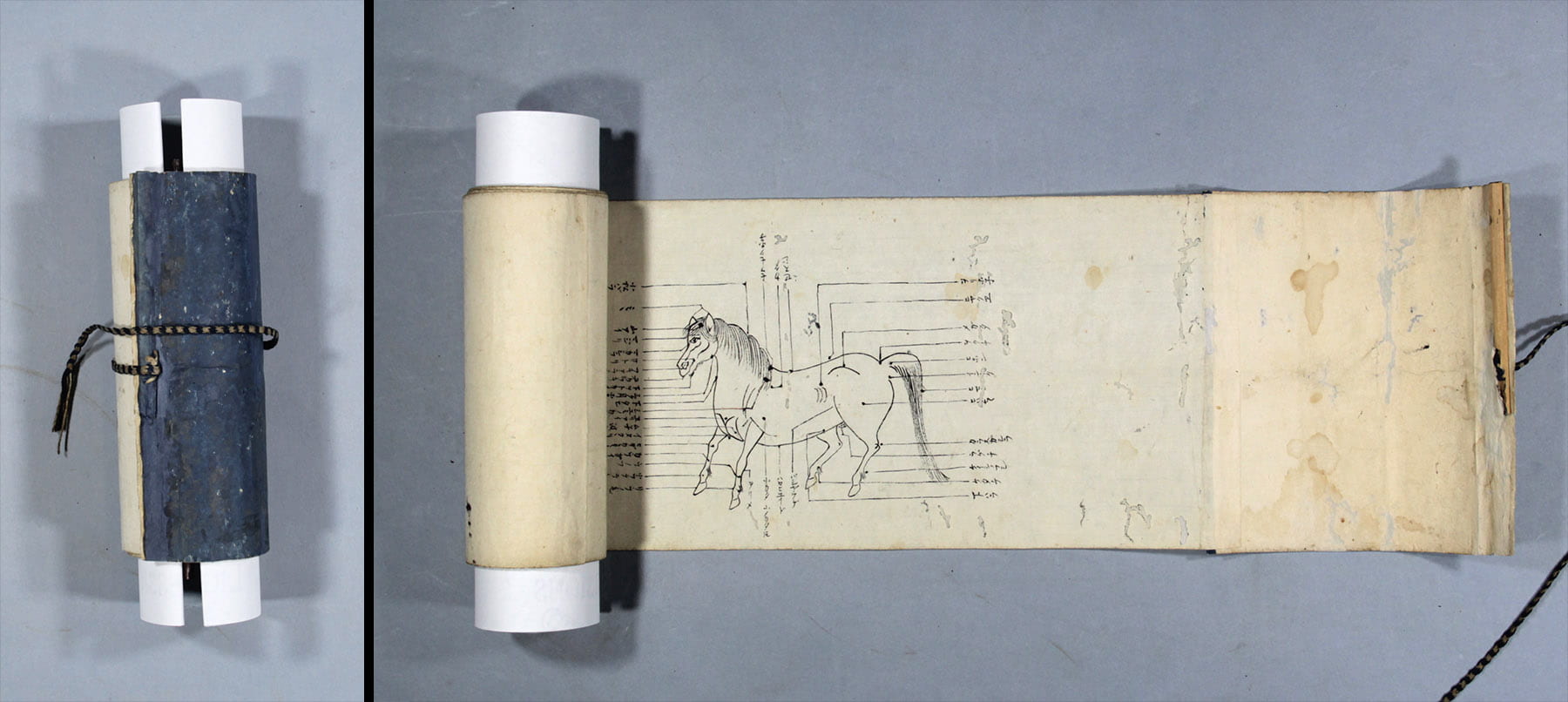

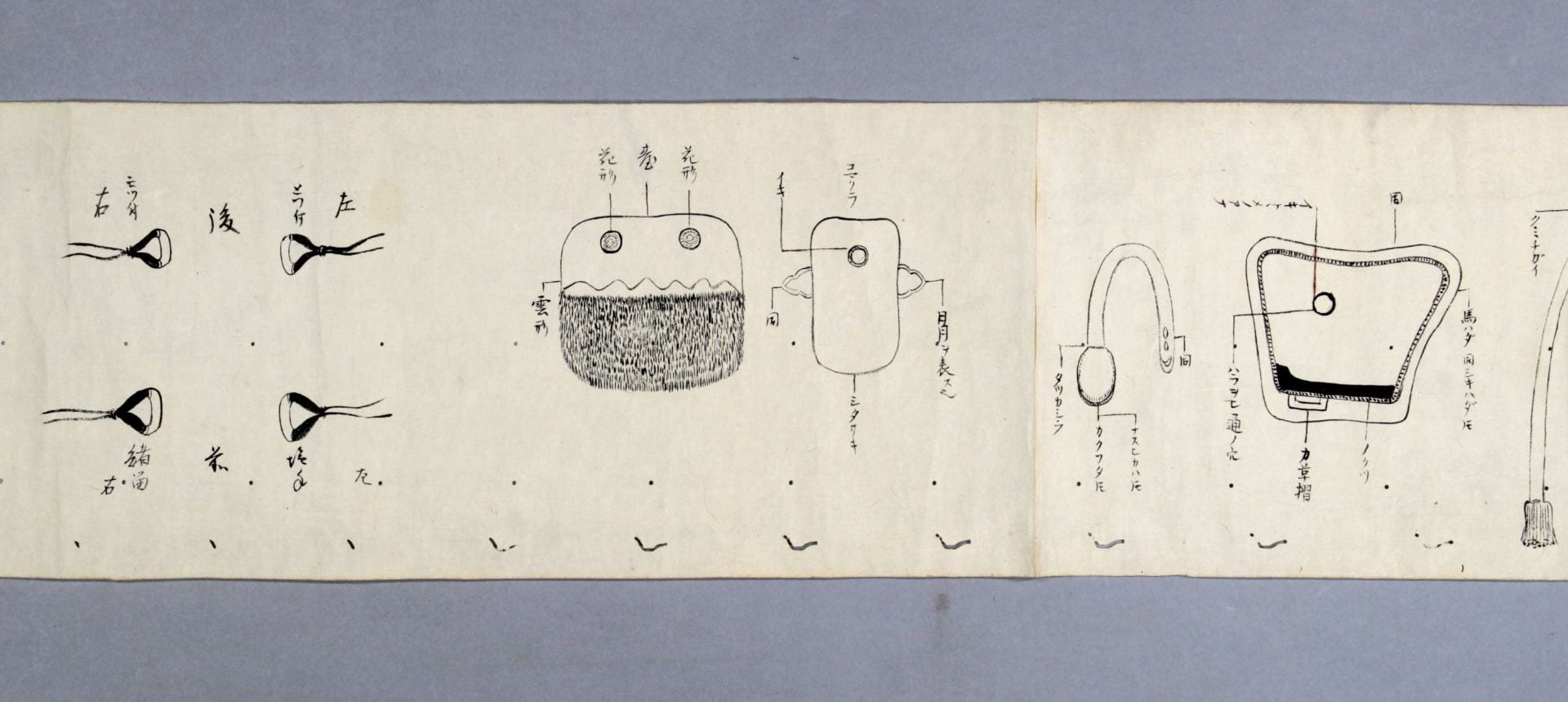

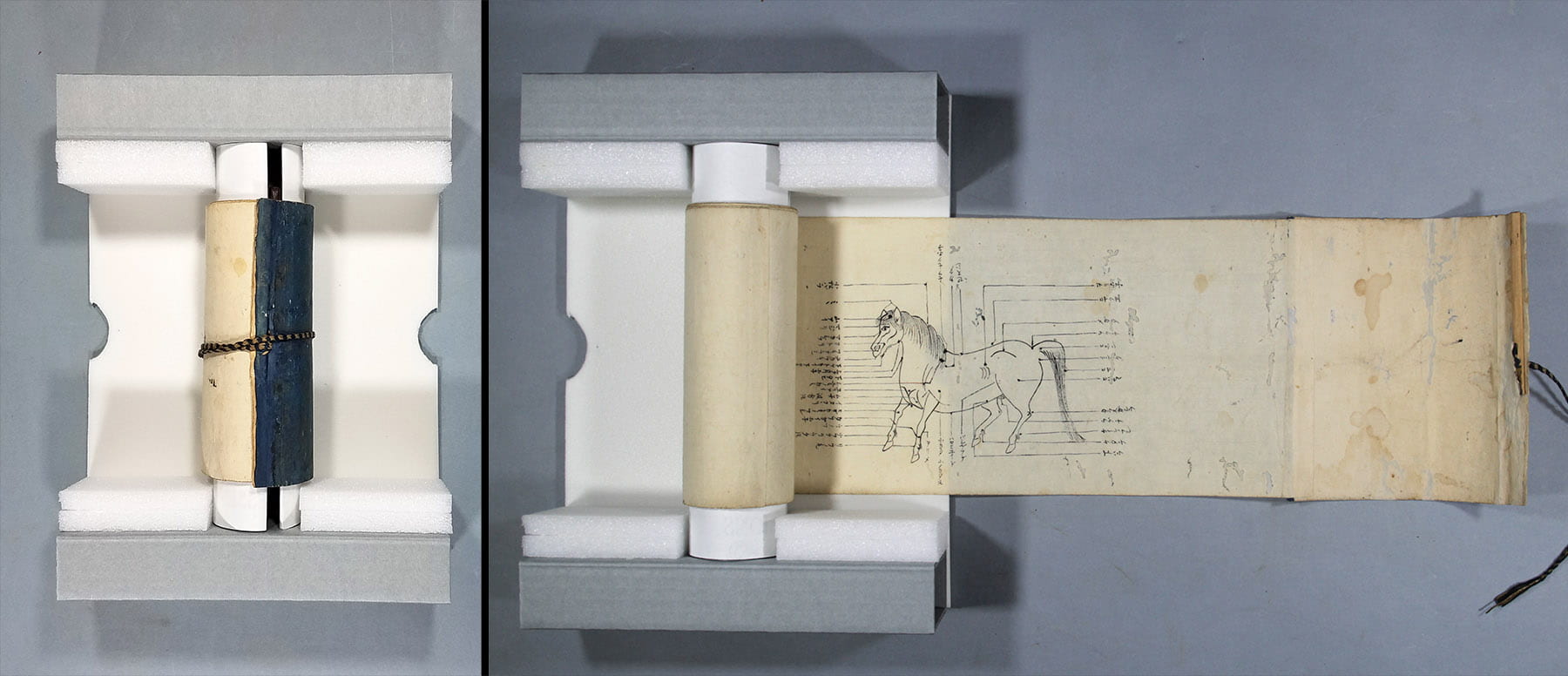

The scroll is a zusetsu, or “graphic dictionary.” It is undated, but thought to be from the 19th century. Our Japanese Bibliographer Daniel McKee, from the Asia Collections, Kroch Library, provided additional insight about the scroll’s content noting that the imagery throughout the scroll is focused on horseback riding with the accompanying text giving detailed names to the parts of the horse and equestrian accessories– saddle, the stirrups, the cinch, the bridle, etc. He explained that in the high court culture of Japan, detailed naming was a way of asserting specialized knowledge and control. On our scroll, this detailed naming went so far as to include the term for the hairs on the back of the horse’s legs.

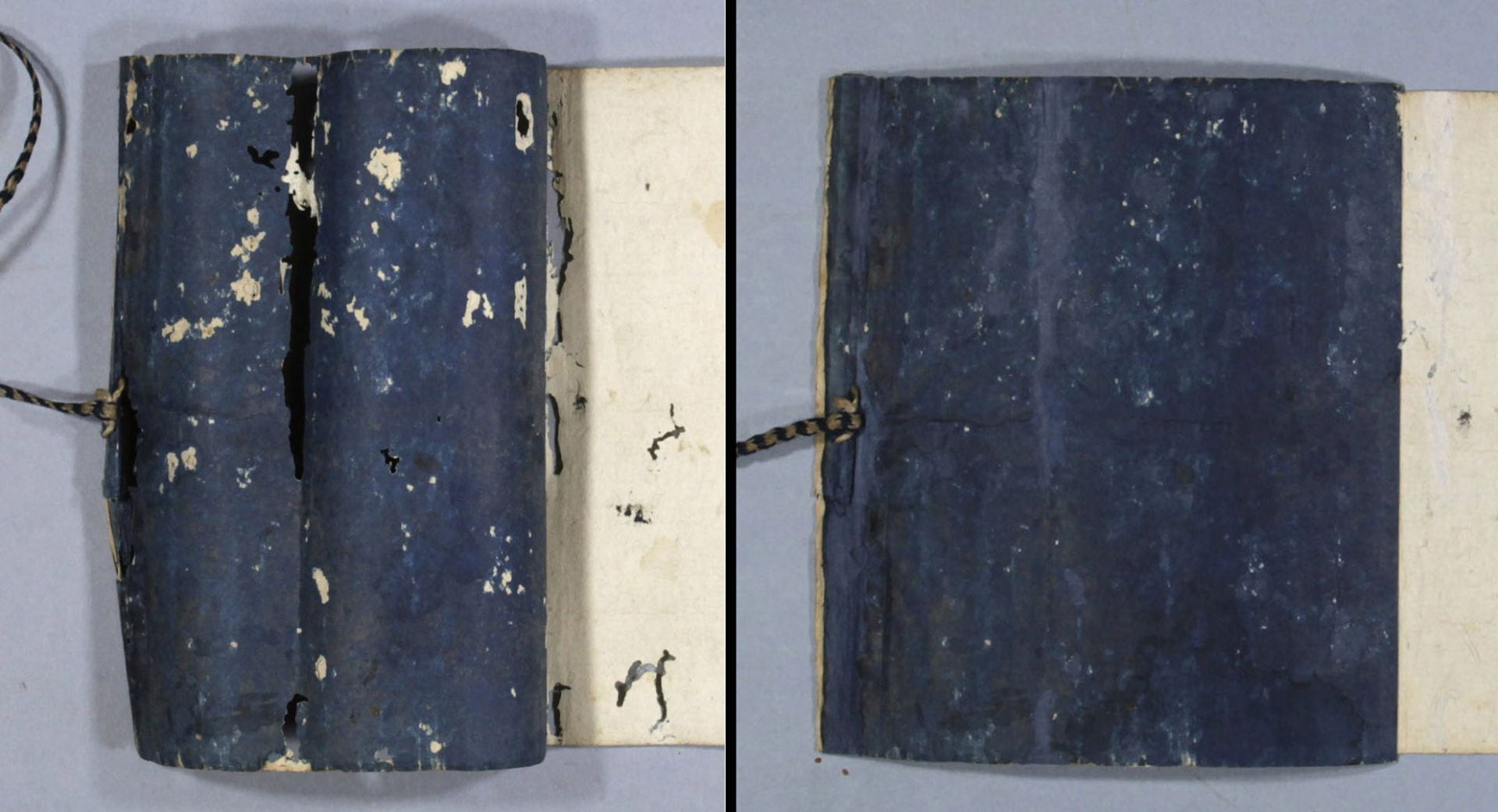

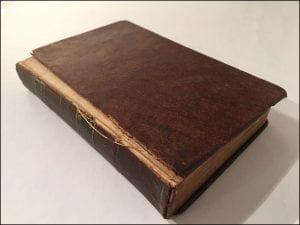

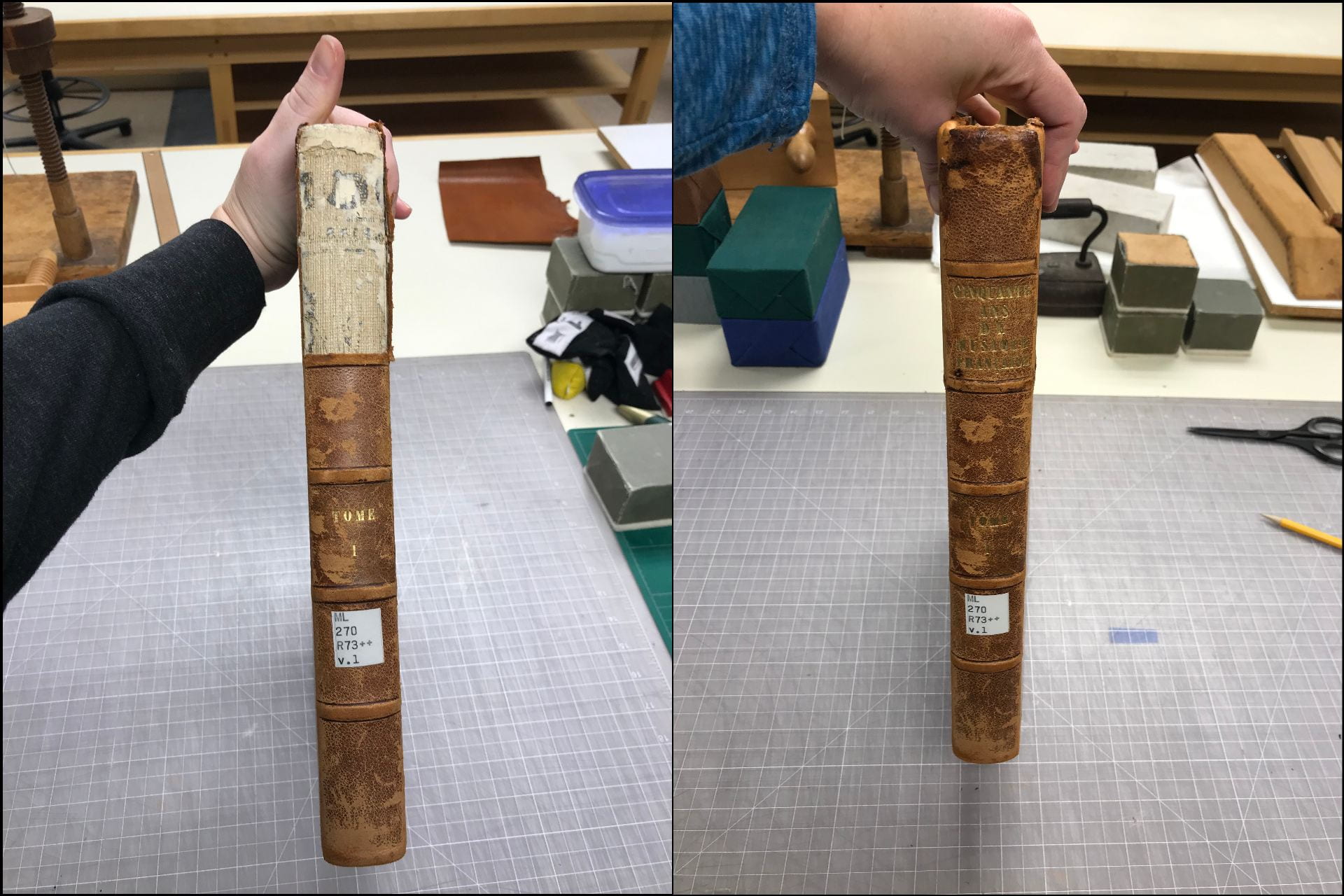

The scroll is composed of six smaller sheets of handmade Asian paper joined together at their edges producing a full length of over 10 feet with a width of approximately seven inches. Attached at the beginning of the scroll, a blue colored leader wraps around to protect the remainder of the scroll. It is uncertain if the blue color of the leader is dyed with indigo; however, the color evokes the past tradition of using indigo dye to denote high status and class.

The scroll is rolled on a thin wooden dowel. A dark blue and tan woven cord attached through a thin wooden slat at the end of the leader helps to further secure the scroll while rolled.

The images and manuscript notations on the scroll are hand drawn in carbon black ink. The condition of the black ink media is very good, with crisp detail and rich black color.

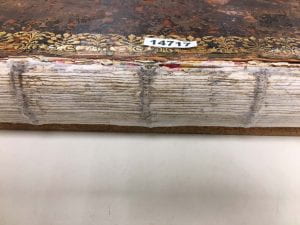

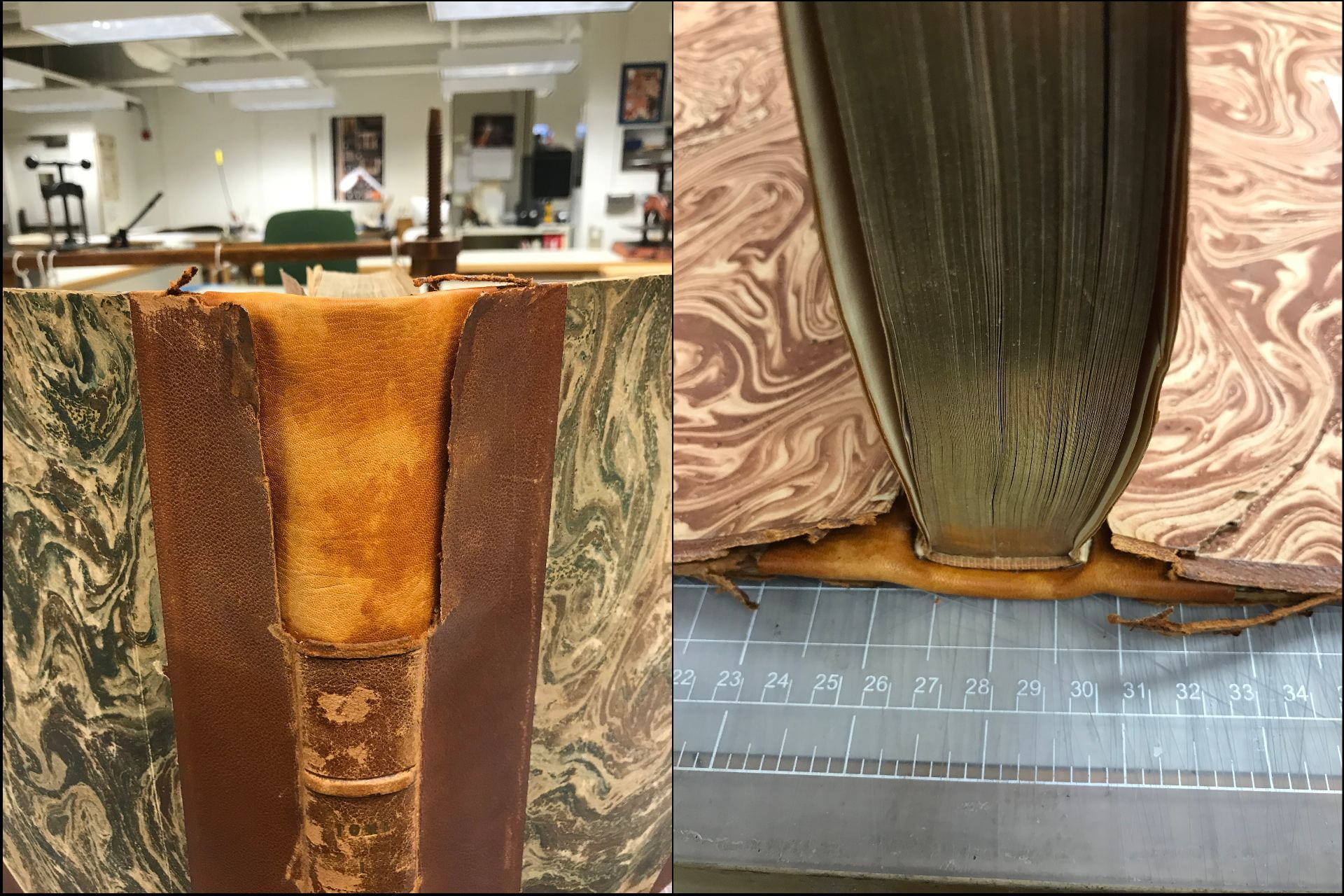

In the past, the scroll was damaged by insect activity while it was rolled leaving portions in poor condition. Insects are attracted to organic materials like the cellulose found in wood and paper. They find nourishment in the proteins and carbohydrates that are found in sizing used to make paper less permeable to ink and the starches found in adhesives. The insect left its mark throughout the scroll in the form of irregularly shaped, yet nearly replicated contours, as it tunneled through the layers of the scroll. This is most evident in the leader and at the end of the scroll where the final section is adhered to the wooden dowel.

Irregularly shaped, nearly replicated contours, seen on the lower edge, tunnel through the layers of the scroll resulting in numerous losses across the scroll.

The paper leader is composed of three layers of Asian paper laminated together, likely with a plant based starch adhesive. The laminated paper layers of the leader are not the same composition as the paper of the scroll. The leader paper layers are thinner and show embrittlement and discoloration while the scroll, aside from the insect damage, remains flexible, showing only some darkening along the edges where it would have been exposed to the environment.

The insect damaged paper with the associated recurrent losses, plus the separation of the paper layers in the leader due to insect damage, made this scroll very fragile to handle and at risk of further damage when used in research or instruction. The goal of conservation treatment was to stabilize the damaged areas and construct a custom housing to provide support and protection.

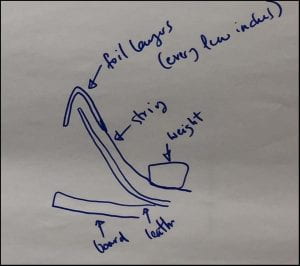

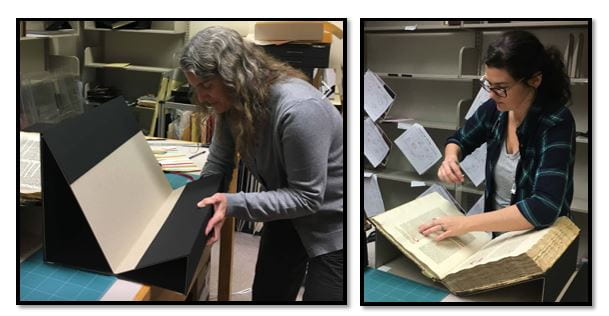

Due to the composition and current condition of the leader, it was not possible to stabilize the fragile areas from the verso, our preferred method. A light table was used to illuminate the area of loss. A protective piece of polyester was placed between the surface of the scroll and the Japanese mending tissue. This allowed the tissue to be precisely shaped to bridge the loss with minimal extension onto the surface of the blue layer.

The small losses found throughout the scroll were mended in a similar manner. The light table was again used to create a precisely shaped tissue to bridge the loss. An additional, slightly larger, mending tissue was placed over the initial mend for a double layer to help match opacity and thickness of the paper. Once mended, the length of the scroll was humidified between felted Gore-tex and dried under weight. Due to the length of the scroll, this was done in two sections. While the first half was under humidification and being flattened, the other half was rolled around an archival tube.

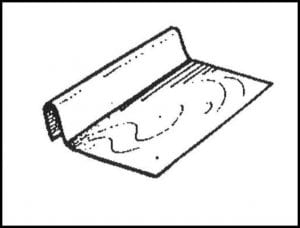

Once treated, the scroll also needed a housing solution that would keep it securely stored as well as provide a mechanism for safely unrolling and re-rolling during use in research and instruction. A channel, just wide enough to accommodate the width of the wooden dowel, was cut into an archival tube to provide support to the scroll, and the scroll then rolled onto the tube. The rolled scroll was placed within an archival box custom fit with a removable tray. The slotted bumpers of the tray securely hold the scroll. This construction allows the scroll to be supported within its storage box while also allowing it, or the tray, to be removed and safely unrolled for viewing.

Viewing the scroll within the tray by manually rolling and unrolling. This construction helped to keep the scroll aligned while re-rolling.

This was a unique item to come into the lab. It provided the opportunity to reach out to colleagues and conservation experts, and to look to existing literature in order to learn more. Many thanks to all those who contributed to the treatment of this scroll and to the writing of this blog, especially Yoshi Nishio at the NEDCC for his insights about the scroll and conservation treatment, and to Michele Hamill, Laurent Ferri, and Daniel Mckee for providing clarity and context about this item and its significance to Cornell’s rare and distinctive collections. Now treated and safely accessible, our equestrian scroll is available to students, faculty, and researchers.

You can read more about Japanese scrolls, their construction, and the unique challenges they present from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Chester Beatty Library.