By Eileen Cuevas

NOTE: This post builds off of a previous post. Please read this post before continuing.

Thanks to Le Corbusier, Chandigarh is known as a bold experimentation of planning. While the history of the city is important, how does modernity affect Chandigarh? To what extent does Le Corbusier’s influence positively or negatively affect the city? Do the residents even care about the tremendous influence Le Corbusier had on the city, or is it just an afterthought? When considering modernity as a Western “bundle of social, ideological, and political phenomena,” it is evident to what extent Le Corbusier’s planning had on Chandigarh (Cooper 2005, 113).

The average meaning of modern would be described as “that which is new, that which is distinguishable from the past,” (Cooper 2005, 113). Because of the city’s radical separation from tradition, its residents have had little interest in brining change to it. Throughout the city’s history, the city itself has seen very little change. Sarin notes that “even after thirty years, development of the road network is dominated by the abstract statements of principle made by Le Corbusier,” (Sarin 1982, 98). Change throughout the city is hindered by Le Corbusier’s work. Also, because of Le Corbusier’s influence on the city, the Town Planning and Architecture departments have “retained a dominant position in influencing major policy decisions,” (Sarin 1982, 98). Not only has the city changed relatively little, the citizens themselves are not content with the way Chandigarh has progressed over the years.

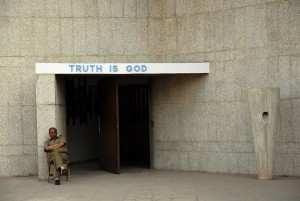

Citizens have described the structures located in the city in various ways, all of which leaves a negative impression of the city. The limits, or failings, of Chandigarh come not only from its explosive, unplanned growth, but also from the design decision that separated its major complex from the city (Fitting 2002, 79). The Secretariat and High Court have been compared to walking inside a “morgue,” and its other buildings have been criticized for using materials that were not indigenous (Kemme 1992, 67). Critics have voiced various negative opinions on the city itself—calling the ideas Le Corbusier built this city on as “alienating,” as well as “highly impractical,” (Fitting 2002, 74). The absence of life on the streets of Chandigarh leaves critics with a sour taste as well (Fitting 2002, 74). Kalia even describes Chandigarh as “safe and yet boring, unIndian and yet an inspiration for Indian architects,” (1987, 74). This view is taken even further as she describes the city as something that had potential, but fell short:

“Chandigarh was meant to be something beyond a new state capital. But it lacks a culture. It lacks the excitement of Indian streets. It lacks bustling, colorful bazaars. It lacks the noise and din of Lahore. It lacks the intimacy of Delhi. It is a stay-at-home city. It is not Indian. It is the anti-city,” (Kalia 1987, 74).

Even the choice of making Le Corbusier the head planner for the city has been questioned by recent citizens, claiming that Le Corbusier “was a good town planner, but he didn’t really understand how Indians live, or what the climatic conditions were,” (Kemme 1992, 67). Residents of Chandigarh also believe that, because of its design, there is no clear “center” of the city (Kemme 1992, 67).

However, at the same time, there has been an increased interest in the city. Because of its position as a city planned by Le Corbusier, many planners and architects had set their sights on seeing what such a city could achieve. As Kalia describes, the rest of the world “closely watched the development of a planned city and the results it would bring,” (1987, 152). In India the city became “an educating experience for India architects and planners, who rushed to other parts of the country to duplicate the features of Chandigarh,” (Kalia 1987, 152).

Overall, Le Corbusier’s influence has had its upsides and downsides. While the city may be an inspiration to some, to its citizens it is merely an eyesore. Little consideration for the Indian way of life had been taken by Le Corbusier, and the city now suffers because of it.

References

Takhar, Jaspreet, and Vandana Babbar. Celebrating Chandigarh. Chandigarh: Chandigarh Perspectives in association with Mapin Pub, 2002.

Cooper, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Fitting, Peter. 2002. “Urban Planning/Utopian dreaming: Le Corbusier’s chandigarh today.” Utopian Studies 13, no. 1: 69-93.

Kalia, Ravi. Chandigarh: In Search of an Identity. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987.

Kemme, Guus. Chandigarh: Forty Years After Le Corbusier. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura, 1992.

Moulis, Antony. 2012. “An Exemplar for Modernism: Le Corbusier’s Adelaide Drawing, Urbanism and the Chandigarh Plan”. The Journal of Architecture. 17, no. 6: 871-887.

Prakash, Aditya. Reflections on Chandigarh. New Delhi: B.N. Prakash, 1983.

Sarin, Madhu. Urban Planning in the Third World: The Chandigarh Experience. London: Mansell Pub, 1982.