by Mary Carol Presutti, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

The ruby-throated hummingbird flew into the porch door window and lay lifeless on the ground. Not ten minutes ago, she had been darting around the yard, along with another female, sipping the necter from my coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) and giant hyssop (Agastache sp.). The two of them had been there on and off all summer, so it’s not like she didn’t have the lay of the land. I could only assume the two girls had been fighting over the honeysuckle, as they are wont to do in a race to put on winter weight, and I guess it got out of hand.

I thought about the little bird now laying lifeless on the ground, it would never make it to wherever she would have spent the winter. Thinking about it, I didn’t know where she would have headed to. Or the route, or the time taken to get there, or if she would eat along the way, or well…anything about her journey.

The remaining bird was sitting on the fence near the honeysuckle looking in my direction. She perched there for maybe five minutes then flew away, and I never saw the bird again.

So, as the little ruby-throated began the first day of her winter journey, I sat down in front of my laptop and began to learn as much as I could about what she would be doing in the days and weeks ahead.

So, as the little ruby-throated began the first day of her winter journey, I sat down in front of my laptop and began to learn as much as I could about what she would be doing in the days and weeks ahead.

After leaving my yard in New Windsor, she would have traveled southwest to somewhere along the Gulf of Mexico. She would fly during daylight, just over the treetops in constant search for food. During most of the flight she had to make sure that her weight stayed high by eating flower nectar, insects, sugar water provided by birders, and interestingly, the sugary and protein laden contents of yellow-bellied sapsucker holes. Her normal weight is between 3 and 4 grams, about the weight of a penny. To prepare for her trip she had to double her weight while she was in New York.

Once she reached the Gulf, there was a final push across the water as she flew nonstop for 500 miles until she reached land. Young and older birds may fly along the coastline into Mexico to reach their destination. My bird may have had the good fortune to alight on a passing boat or possibly an oil rig for a short rest. It is an amazing journey for such a tiny bird.

Once she reached the Gulf, there was a final push across the water as she flew nonstop for 500 miles until she reached land. Young and older birds may fly along the coastline into Mexico to reach their destination. My bird may have had the good fortune to alight on a passing boat or possibly an oil rig for a short rest. It is an amazing journey for such a tiny bird.

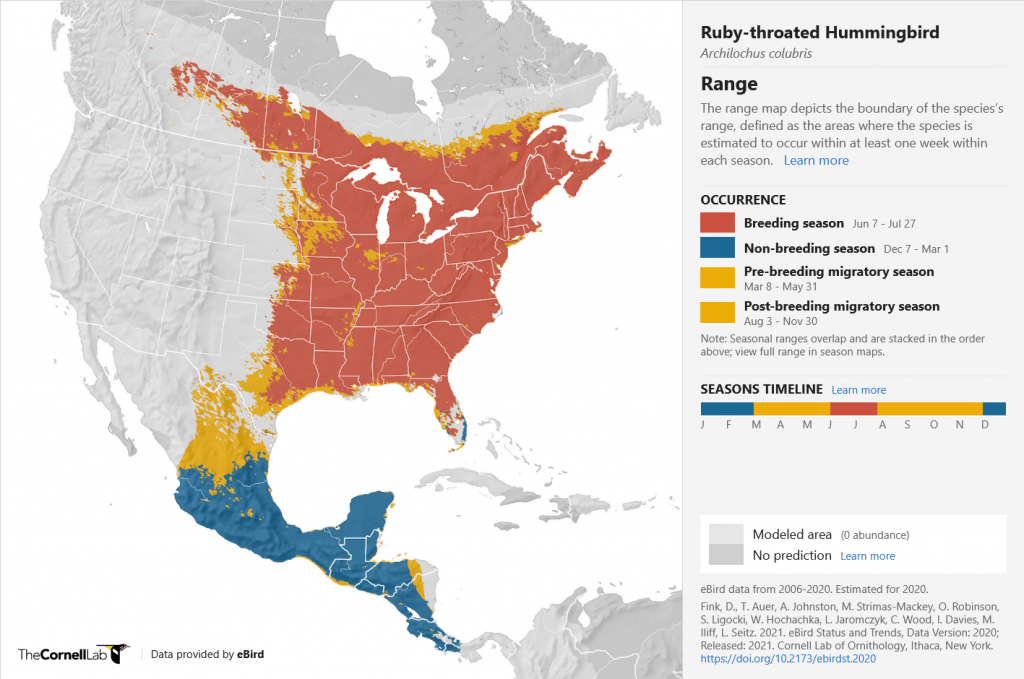

It is now December so the ruby-throated hummingbird who, in September, perched on the fence watching me, has by now made the long 1600 mile or more trip to one of a few locations in Mexico and Central America. However, there is a chance that she may be wintering in one of the southernmost states. In the last 25 years with the temperature change, the ruby-throated hummingbirds’ range has expanded 200 miles north of its traditional southernmost range.

Sometime in March the trip back north will begin and by the end of April to mid-May she will arrive close to where she was born, ready to find a suitable mate, raise her chicks, and prepare for another fall flight.

Interesting Facts about Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

-

Male ruby-throated hummingbird Research indicates that a hummingbird can travel as many as 23 miles in one day. They fly by day and use tail winds to help conserve energy.

- In eastern part of the United States the ruby-throated hummingbird is the only breeding hummingbird around. Males arrive in New York a few days before females to set up territories

- Bird banding projects show that when ruby-throated hummingbirds head south, they will follow almost the exact route they took a few short months ago when they were heading north to their breeding grounds. Young birds will return to the location in which they were hatched.

-

Juvenile red-throated hummingbird Several species of hummingbirds including the ruby-throated hummingbird follow yellow belly sapsucker woodpeckers to feed on the remaining sap and bugs left over from the holes the sapsucker drills into trees.

- Hummingbirds eat between 60 and 80% of their protein a day in insects. That’s about 330 fruit flies a day!

- Ruby-throats will occasionally hybridize with black-chinned hummingbirds where the ranges of the two species overlap.

-

Female ruby-throated hummingbird on nest Hummingbird feet are poorly developed, so if they want to move a few inches while perched they must fly.

- A group of hummingbirds is called a charm, but you will seldom see a group of hummingbirds gather willingly outside of backyard hummingbird feeders. Hummingbirds are territorial and can be aggressive when food is involved. The dominant male controls which hummingbirds feed in his territory. He sits nearby the feeding area and will attack any other males or females that dare to attempt to feed in his territory. Female hummingbirds that are sociable towards the dominant male are allowed to feed unscathed.

More Information about Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

Attracting Hummingbirds – Penn State Extension

Central America Bird Feeder Live Feed – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Hummingbird Migration – Hummingbirds.net

Hummingbird Sightings – Journey North

Ruby-throated Hummingbird – National Audubon Society

Understanding Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and Enhancing Their Habitat – University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Mock orange shrub (Philadelphus virginalis): This late-blooming deciduous plant provides a stunning citrus fragrance and can be used in groups as screening or as a stand-alone specimen. They also make excellent cut flowers indoors. It’s not a true orange, and its name supposedly derives from the fragrant white flowers which in some varieties resemble that of orange blossoms.

Mock orange shrub (Philadelphus virginalis): This late-blooming deciduous plant provides a stunning citrus fragrance and can be used in groups as screening or as a stand-alone specimen. They also make excellent cut flowers indoors. It’s not a true orange, and its name supposedly derives from the fragrant white flowers which in some varieties resemble that of orange blossoms. Phlox (Phlox paniculata): This native American wildflower is also known as garden phlox and summer phlox. They are sun-loving perennials with a long flowering season. Phlox are tall-eye-catching plants with large clusters of pink, lavender or white flowers, called panicles. They bloom for several weeks in summer and make excellent cut flowers.

Phlox (Phlox paniculata): This native American wildflower is also known as garden phlox and summer phlox. They are sun-loving perennials with a long flowering season. Phlox are tall-eye-catching plants with large clusters of pink, lavender or white flowers, called panicles. They bloom for several weeks in summer and make excellent cut flowers. Goldenrods (Solidago spp.): A native to the United States,

Goldenrods (Solidago spp.): A native to the United States,