We are still seeing continued emergence of Apple Maggot adult fly (AM), Rhagoletis pomonella. The rains on August 21st accumulated 0.75″ with no rain since that date. Despite the flush of flies, effective applications made after the 21st of August in the mid-Hudson Valley will likely control the egg laying by flies moving into September.

Employing a generic IPM and Resistance Management approach is essential for the majority of researchers and growers who see resistance management (RM) as an important and foundational concept in retaining control of our primary insect pests. If we look at the potential of specific insects to acquire insecticide resistance, we should place them into categories of potential risk to better understand how best to use our tools to maintain the control of the insect pest complex.

The separation of pest groups with regards to resistance development and management can be looked at by assessing insect habitat and ecology. Insect pests that seem most likely to acquire insecticide resistance include those that have multiple generations, those that are endemic (stay in a local ‘orchard’ environment) with constant exposure to tree fruit host and insecticides, those that are less mobile and thus limited in exposure to highest level of residual activity, those that have limited or local migratory capacity.

However, its very interesting to note that major insects such as plum curculio and apple maggot have not been documented to have acquired insecticide resistance to the principle insecticides used for the past 50 years such as phosmet (Imidan) and azinphos-methyl (Guthion).

One of the ecological habits of these insects include a host range outside the orchard that provide populations for mating of individuals that have not been exposed to pest management tools. These individuals are capable of diluting their genetic base, through mating with susceptible individuals, to maintain levels of susceptibility to pest management tools. This does not preclude the development of resistance but plays an important role in limiting and postponing insecticide resistance development.

by multi-coloured Asian lady beetle.

The use of Assail 30SG has and continues to be an important tool for use against the apple maggot. It’s late season activity against the AM also provides excellent management of late season rose and white apple leafhopper, that can reduce harvest efficiency in high numbers as an annoyance pest to fruit pickers.

Assail will also control the late season aphid complex. These insects can become problematic if late season rains promote flush growth. New growth provided resources for development of abundant green (GAA) and spira aphid (SA) that feed on new stems and leaves causing sooty mold development on fruit. Very high populations can move to fruit and cause both fruit injury and at harvest, presence of the fruit going in and out of storage.

High GAA/SA promote high ladybird beetle larval populations that may pupate on fruit, causing holes from larva mouth parts that embed on the fruit surface.

It is an excellent material against 3rd generation oriental fruit moth and codling moth when present while providing some suppression of San Jose scale if a 3rd generation appears in mid-late September.

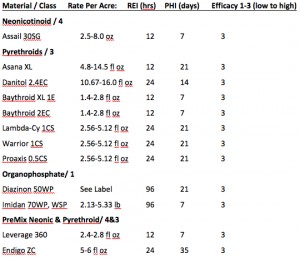

That said, the labeled constraints that direct the use of Assail 30SG label limits the use to :

* 4 applications per season.

* 12 day reapplication interval.

* 7 days before harvest

* Total of 0.60 lbs. active ingredient (32.0 ozs. product) per acre per growing season.

The guidelines for resistance include avoiding making more than two (2) consecutive applications of ASSAIL 30 SG Insecticide before rotating to an alternative mode of action insecticide.

Although I agree with this consideration for all aphids, scale, codling moth, I don’t agree with this ‘suggestion’ for apple maggot for the reason stated above. As stated earlier in the text, AM flies migrating from alternate hosts outside the orchard are likely to arrive with other adults with susceptible genetics, not having been exposed to insecticides during previous generations. With a single generation per season and occupation of alternate host on a yearly basis, its unlikely that AM, migrating from outside the orchard will develop insecticide resistance to Assail.

Its important to note that making multiple successive applications against this insect upon trap threshold within a single generation is in line with resistance management strategies for other pests in need of this strategy. Skipping a single spray and alternating insecticide classes during a single generation does nothing for RM.

Rotation should occur yearly for AM using a different class of insecticide, given the single generation of this insect. One approach might be the use of Assail (IRAC Class 4) in 2016 followed by another classes used in 2017 and still and third in 2018, returning again to Assail in 2019.

With regards to neonicotinoids, they differ greatly in their direct toxicity to honeybees. The use of Actara during petal fall has the greatest negative impact to honeybees given the presence of orchard floor plants in bloom. Calypso had the least level of toxicity with other neonic’s falling in somewhere in-between.

The use of Assail late season for AM management will most likely have a lower level of impact then earlier applications given the lower population of flowering on the orchard floor and perimeter. Most honeybee colonies and solitary bee populations will have rebounded with robust presence by mid-July.