Herd Mentality in the Cessation of Smoking Habits

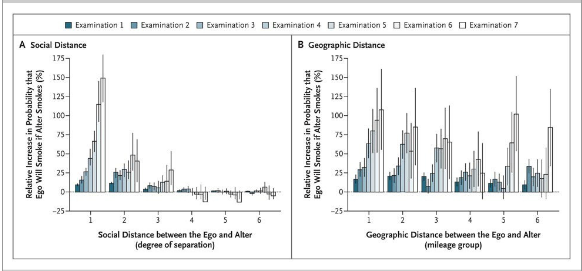

The place of cigarettes in society has changed greatly in a span of 2 score. The prevalence of smoking in the United States has reduced from 45% to 21% in the past 4 decades. Research studies conducted by Dr. Nicholas A. Christakis and Dr. James H. Fowler track the manner in which the cessation of smoking has spread throughout social networks. For a period of 32 years from 1971 to 2001, smokers and their social networks were observed for the initiation and cessation of smoking. A common phenomenon in the networks was the presence of strongly tied clusters of smokers as well as clusters of non-smokers. The risk of smoking among contacts of a subject who was a smoker was 61% higher than risk of smoking observed in a random network. Similarly, a contact of that contact, 2 degrees of separation from the subject, also had a 29% higher chance of being a smoker. Even at 3 degrees of separation from the smoker subject, the effects of the smoker cluster were still felt.

The presence of these smoking clusters could be explained by the idea that subjects may choose to associate with people with similar smoking behaviors. It has been seen that since 1971, social networks have become more polarized. There are more clusters of smokers and nonsmokers and fewer ties between these separate groups in 2003 than there were in 1971. The presence of these separate smoker and non-smoker clusters could also be because subjects and their contacts are all exposed to similar environmental factors that may lead them into smoking. Another explanation for these separate smoking and non-smoking clusters is the possibility that contacts have induced subjects to adopt their own smoking behaviors.

It was hypothesized that the strongest behavioral influences would be caused by mutual friendships, followed by subject perceived friendships. Contact perceived friendships were hypothesized to cause the least influence in the subject’s behavior. This hypothesis was proved true. When a contact in a mutual friendship ceased smoking, the subject was 46% less likely to also cease smoking. When a contact in a subject perceived friendship stopped smoking, the probability of the subject being a smoker decreased by 36%. However, when a contact in a contact-perceived friendship ceased smoking, there was no noticeable effect in the subject’s behavior.

This data demonstrates the herd mentality found among smokers. If one’s friend stops smoking, it may be because the friend has learned new information. For example, when the study first began in 1971, all the dangers of smoking were not nearly as commonly known as they are now. It is entirely possible that the initial spread of the cessation of smoking through a network began as one person learned new information and spread it to his or her friends. As everyone else in one’s friend group stops smoking, one may be influenced to do the same, thinking that there is some new information that has caused everyone else to cease their smoking habits. In this way, the spread of the cessation of smoking through a network could have been caused by an indirect benefit that others know information that the subject may not have himself known.

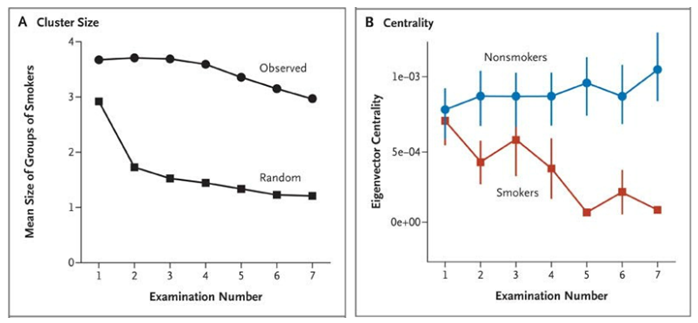

On the other hand, there are also direct benefits in the cessation of smoking. Regardless of the immense health and economical benefits from stopping smoking, there is also a direct social benefit to ceasing smoking if one’s social network begins to trend away from smoking. It was seen in Christakis and Fowler’s studies that as more and more people in one’s social network stopped smoking throughout the years, smokers moved toward the periphery of their social networks. They were less accepted by their peers as their friends all began to stop smoking. This can directly cause the subject to cease smoking in an attempt to fit in better. The study shows that in 1971, there much higher number of smokers in comparison to now. Back then, the frequencies of smokers and nonsmokers in the center of components were about equal. However, now as smoking becomes less common, the frequency of smokers in the center of a social network component is less than that of nonsmokers. It was found that smoking seems to decrease centrality, however centrality does not cause one to decrease smoking. This seems to say that if one is already in the center of a component, there is no added social benefit by quitting smoking. However, if one is more toward the periphery of a network, there can be a higher social incentive to cease smoking and hopefully become more accepted.

This herd mentality in the cessation of smoking can also be corroborated by the occurrence of local smoking cessation cascades. It was observed that whole connected clusters stopped smoking at roughly the same time. This implies that decisions to quit smoking are not individual choices. Rather, whole groups of people with up to three degrees of separation all tend to act under collective pressures to stop smoking. This is possible because these people are exposed to a similar environment and may experience something that may inspire them to quit smoking, like the illness of a common smoker friend.

Christakis and Fowler also recorded the effects on a subject’s behavior caused by contacts that were geographically distant from the subject. It was seen that geographical distance did not dilute the effect of a contacts behavior on the subject.

This seems to show that simply copying behaviors is not the only effect contacts can have on subjects if physical proximity is not even needed for the phenomenon to spread. To that effect, it seems that the actions of a subject’s contacts actually changes that subject’s view of social norms about smoking. If all the subject’s contacts are smoking, it will seem the social norm for the subject to pick up smoking. In contrast, this study saw that as the subject’s contacts stopped smoking, this seems to give the subject an indirect reason to stop smoking. The subject will view it as a social norm to cease smoking and will join in the trend, perhaps thinking that his friends know something he does not.

In behaviors such as choosing to cease smoking, the decision is often wrapped up in societal pressures and ideas. The actions of a subject’s contacts can have a large effect on the subject himself. The subject tends to follow the behavior of contacts for many direct and indirect reasons. Indirectly, the changing views of his friends may cause his own views of the social norm to change. The subject may be swayed to change his behavior if he believes his contacts have changed their behaviors based off of extra information that he himself may not be privy too. The act of ceasing smoking can also come about due to direct benefits. For example, as one’s social network becomes increasingly intolerant toward smoking, it is mist socially beneficial to the subject for him to also cease smoking in order to fit in better with his social network.

-pb

References:

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa0706154#t=articleResults