This has been a tough year for trees. On top of drought conditions, Gypsy moth caterpillars, also known as Lymantria dispar dispar (LDD) caterpillars, have been defoliating trees throughout our region, including Northern New York, Vermont, and Southern Canada. Our St. Lawrence County Extension garden hotline , “the Growline” (SLCGrowline@gmail.com) has received many calls and emails from homeowners distressed at the damage they are witnessing. Some have sprayed with little or no effect as the caterpillars munch their way through their ornamentals and large shade trees.

The situation may seem dire, but the six Master Gardener Volunteers who serve as Growline moderators have distilled some great resources that can help us understand and manage the LDDs this year and in future years. This article covers the background and life cycle of this invasive species, tips for dealing with caterpillars and egg masses, and how to support affected trees through this stressful time.

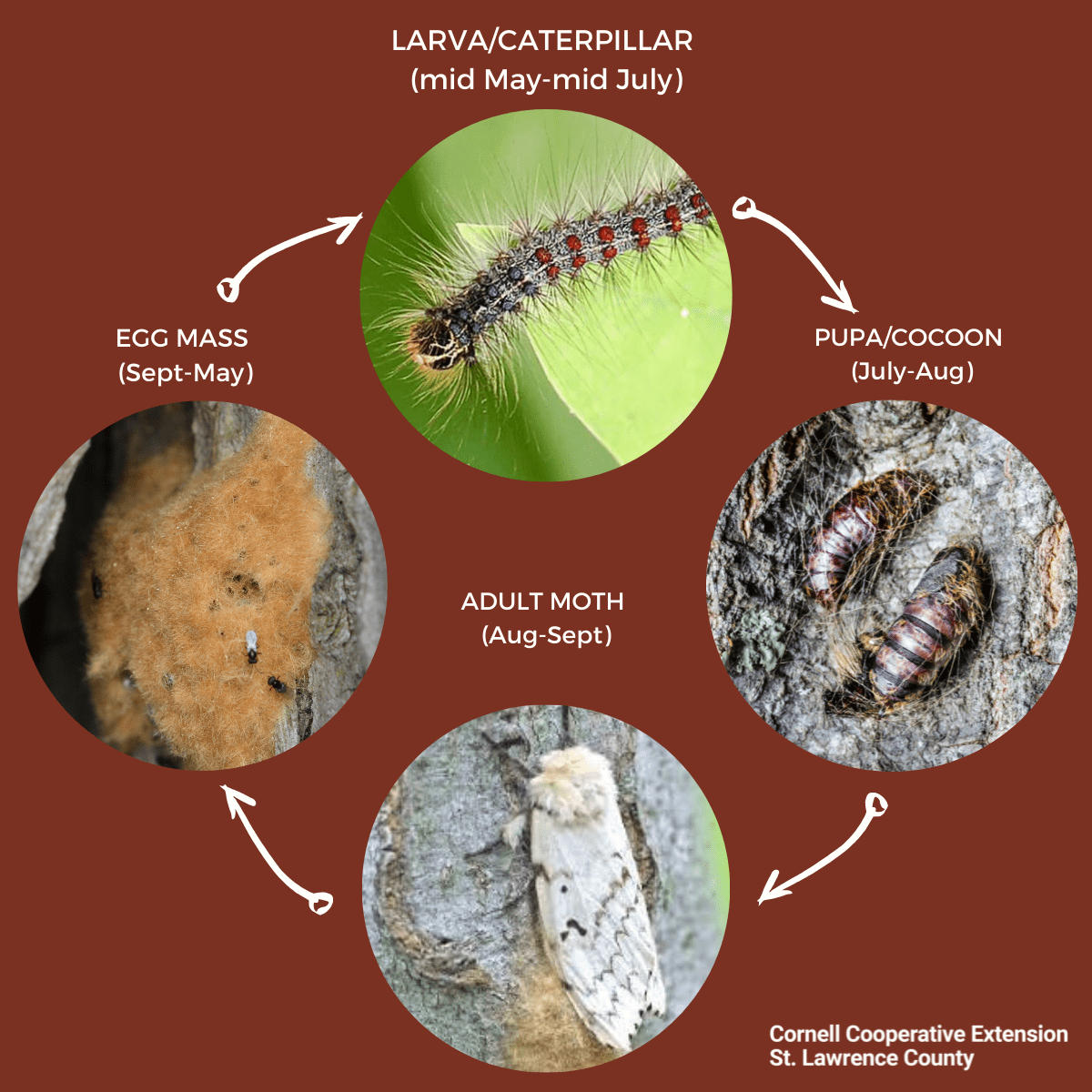

Timeline

LDD caterpillar populations rise in years with mild winters and dry springs, and decline in wetter years due to a fungus called Entomophaga maimaiga that can spread through the population and keep them in check. Our current “moderate drought” and rising winter temperatures have played a major role in the current outbreak which began in 2019, grew in 2020, and is set to exceed 2020’s damage this summer. Despite this fungus, viruses and many other natural enemies, significant outbreaks have occurred in 1985, 1991 and 2002.

While each LDD infestation is different, with different areas bearing the brunt, the progression of defoliation through the spring and summer closely follows the life cycle of the LDDs. Tiny caterpillars hatch within “egg masses” on trees in May. According to DEC Forester and Arborist Rob Cole, who hosted a June 25th webinar on LDD caterpillars, “The defoliation becomes noticeable late May/early June and then it hits its peak the last week of June or so. Once those caterpillars reach their largest larval stages they’re eating a lot of leaf material, a square foot or more a day.” By mid-July the caterpillars pupate, marking the end of the defoliation. The adults emerge in August as moths that mate and lay eggs.

Because we are now at the tail end of the defoliation stage of the infestation, controlling the caterpillars is not realistic, but we can monitor trees for egg masses this fall, and support affected trees through this stressful time.

Identification

In order to scout for and control LDDs in any stage, it’s important to do some identification. Many of our callers assume they are seeing tent caterpillars, and have never heard of LDD (or the more common name, Gypsy moth) caterpillars.

This is a helpful graphic that simplifies the identification of three common hairy caterpillars, each of which eats tree leaves. Note that only the LDD has a yellow head with black markings and sets of spots along their backs in blue-grey, then reddish-brown further from the head. They do not create silk tents, and their preferred meals come from apple, oak, aspen, birch, maple and willow, though they have been known to feed on hundreds of other species once their top choices are bare. Larger caterpillars will even feed on conifers like pine, hemlock, and cedars. Using reliable websites or emailing the Growline with a good picture are both good places to start if you’re seeing caterpillars on your trees.

Where did LDDs come from?

Lymantria dispar dispar moths haven’t always wreaked havoc in our northern forests. LDDs are in fact native to Europe and Asia, and were accidentally released in Massachusetts in the 1860s by astronomer and amateur entomologist Étienne Trouvelot, who wanted to test their potential for manufacturing silk. Their range has expanded considerably over the last 150 years and infestations now affect about half of U.S. states with severe ones occurring every 10-15 years and usually lasting 1-3 years.

Management techniques

While small caterpillars can be managed using a product called Btk or Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki, large trees are not easily treated by homeowners and even a modest amount of spraying can be cost-prohibitive. Without coordinated and widespread aerial spray programs many people are left to watch as the trees around their homes are denuded.

One management technique feasible on a small scale is making burlap traps by tying a band of burlap around affected tree trunks at about chest height. The caterpillars like the shade and hide underneath during the day, or get caught in the layers when returning to the canopy at night after spending the day on the ground. Picked them off (with gloves on!) at least once a day and drop them into a bucket of soapy water. Continue to monitor for pupae in their cocoons, or light brown egg masses, which appear later in the summer and into fall/winter. Use the same soapy water method if squishing caterpillars or eggs makes you squeamish.

Note: the hairs on these caterpillars can be irritating, causing itchy bumps on the skin, so use gloves or tools rather than bare hands, when picking up, brushing off, or crushing gypsy moth caterpillars.

The outlook for our trees and how we can help

While a healthy, leaf-bearing tree can survive a year of defoliation and may even leaf out a second time in late summer with smaller leaves, most trees can not endure multiple years of defoliation. In addition to the diminished capacity to make and store energy, trees weakened by summer defoliation are more vulnerable to pests, diseases, or even competition from invasive plants around their base. If possible, give them extra care by watering deeply in dry conditions, weeding around the trunk, mulching properly with 1-2 inches of organic material, and monitoring for egg masses in fall/winter. Do not fertilize the tree until next spring. Doing so now can cause a flush of new growth that will not have time to harden off and go dormant before the first frosts.

According to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, “If your tree lost ALL its leaves and does not grow any new ones in the next two months or so, watch it in the spring. If it still does not leaf out next spring, it has died.” You should contact an arborist if you have concerns about a sick or damaged tree, especially if it could endanger a house if it were to fall.

Keep in mind that many of the large shade trees around us have survived previous caterpillar infestations. With extra support, our trees may survive this stressful time and regain their health.

More information

- St. Lawrence County Extension garden hotline: SLCGrowline@gmail.com

- St. Lawrence County Extension Gardens and Grounds page

- The University of Wisconsin Extension has a helpful calendar of recommended LDD controls for homeowners

- More LDD lifecycle and control methods from the NY DEC

Erica LaFountain is Community Horticulture Educator and Master Gardener Coordinator for St. Lawrence County. She has a background in organic vegetable farming, gardening, and orcharding and has a homestead in Potsdam, NY.