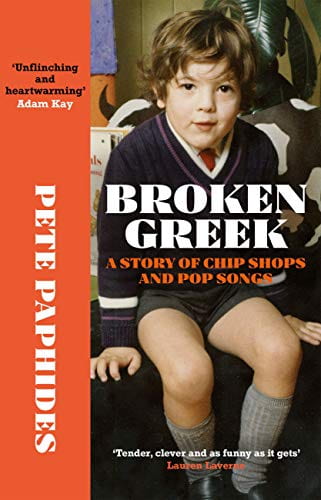

Acclaimed music critic Pete Paphides’s autobiography is a vivid account of a life illuminated by music.

“Do you sometimes feel like the music you’re hearing is explaining your life to you?” Broken Greek, by acclaimed British music journalist Pete Paphides, is a love letter to the magic of those electrifying, heart-rending and profoundly cathartic moments. In equal parts an autobiography and a pop music retrospective, Paphides assembles glittering fragments of daily life – his cross-cultural upbringing, scrappy schoolyard games of English football, the wonders and anxieties of boyhood and the music illuminating it all – into a kaleidoscopic diorama of growing up in the 1980s in Acocks Green, Birmingham. With unfailing wit, candour and compassion, Paphides pays homage to the pivotal role of music in our lives and how the personal is deeply intertwined with the larger cultural moment.

Paphides’s debut novel is about his halting, broken greek, his displacement from the cultural world of his immigrant parents, his gruff Cypriot father, Christakis Paphides, and his doting Greek mother, Victoria Paphides, and the yawning chasm between the family dinner table and the world beyond his front door a young, skittish Paphides had to cross. But this is more than a tale of insufficiencies. Over the ten years the book covers, we watch Paphides emerge from his four year long spell of selective mutism to venture into the unpredictable, technicolour the world beyond, and find the confidence to take his place in it.

In spite of the book’s weighty subject matter – marital rifts, cultural displacement, the history of pop music itself – Paphides is undeniably hilarious. Despite the associations of long-windedness a 600 page debut novel tends to confer, Paphides’s writing is taut with insight and humour. Testament to his journalistic training, his writing marries character with concision, interspersing the profound and even the heartbreaking with zingers on his childhood escapades. Surging from one quip to the next, Paphides hurtles over large swathes of narrative ground, his readers in tow.

51-year old father of two though he may be, Paphides is phenomenal at inhabiting the headspace of a 7-year old. He is resonant on the fears and foibles and guileless wonders of childhood, no matter how far into their past that may be for some readers. As someone with scattered memories at best of anything that happened before I was 10, I am in awe of his childhood powers of recollection and the sheer amount of detail he marshals. He captures the almost irrational but deeply intuitive way children react to music and the world around them, recalling how at age 7, the forlorn crooning of a Greek song his father enjoyed, “Cloudy Sunday” (Sinefiasmeni Kiriaki), shrouded him in a pallor of “imminent peril,” compounded by the disquieting sense that the pagan sun on the record sleeve was staring at him. The book narrates the series of anxieties the timid but winsome younger Paphides cycled through, ranging from the inane, like children’s television star Jimmy Osmond, to the morbid, such as his parents’ abandonment. Paphides also pays homage to the enduring role of music as “a periscope into (the adult) world,” a thrilling gateway of discovery for children. With minor adjustments, the scene he recounts of himself and two others whipped into an exhilarated frenzy by cameos of entry-level expletives in “Greased Lightnin’” could have been plucked from any reader’s childhood.

Paphides leaves no room to doubt his journalistic credentials. Wielding the language of cultural critique with panache, he traces the arc of various musical styles and their accompanying aesthetics, bursting into and trailing out of vogue, and the intricate webs of calls and responses woven throughout the pop ecosystem. Paphides is in his element writing about pop music, authoritatively capturing the zeitgeist of a musical era in the turn of a phrase. Of the 1980s English 2 Tone and ska revival bands, he writes that they were “unified by an aesthetic that felt like the logical third act in the wake of the nihilism of punk and the crafted ennui of new wave.” Even when outside the remit of his musical expertise, Paphides is cogent on the historical and musical context of his father’s favoured Greek music. He narrows the cultural gulf by highlighting the parallels to British pop, giving us a glimpse into his multicultural upbringing where these two cultures were different, but not separate.

Though Paphides is separately competent as an autobiographer and a music journalist, what distinguishes Broken Greek is his marriage of the two. He lifts the latch on his innermost world where the chorus of ABBA’s “Money, Money, Money” coloured the silhouette of his father, bent over a chip fryer, toiling to provide for his family, strains of David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes” curled themselves into the locks of his mother’s hair, splayed against the pillow of a hospital bed, and Leo Sayer’s “When I Need You” spoke for him in his petrified silence, wracked by guilt for his mutism.

Rather than unravelling an imperial history of British pop music, developments in pop are told first through the eyes of Paphides the younger as a shortlist of potential adoptive parents from the Top of the Pops’, BBC’s weekly music chart show, to be tapped on if and when his parents abandon him. Paphides narrates the history of pop through the lens of what these songs meant to him. He describes how artists lent him the words and melodies for his nascent meanings as he navigated familial tensions and struggled with his perpetually dismal position in the schoolyard pecking order. Over the years, the varied artists gracing the radiowaves and record player were simultaneously chilling soothsayers presaging his fears for the future, spokespersons for his desires, and cooler, more confident versions of himself. Paphides pinpoints the impalpable yet powerful sense of communion we share with our music, declaring that music does not amplify our emotions, but that reality “(authenticates) the sentiments of the song.”

He is a faithful scribe not only to his own relationship with music, but also the musical obsessions of the people around him. He chronicles his brother and friends’ adolescent evolution accompanied and led by music. Writing about his brother Aki’s obsession with The Teardrop Explodes and neighbour Emily’s devotion to Adam Ant, he underscores how music could be an epiphany, a revelation not just about what music could sound like, but how you could dance, dress or talk. Who you, a hungry teenager facing the wilds of the world to come, could be. Even if Paphides does not inhabit his parent’s cultural universe, he reimagines their reality with compassion and patience. “For them music didn’t exist to enhance the present. It was a means of temporarily obliterating it” he writes. His parents’ indifference to the British pop juggernauts and his father’s insistence on Greek music are presented not as wilful ignorance, but reflections of the gruelling realities of supporting a family as immigrants cut loose from existing support structures.

Broken Greek held my attention even though I am barely literate in the pop music canon of the 1970s and 80s, not an immigrant to the United Kingdom experiencing cultural displacement, or a fifty-something primed to gush with nostalgia by sepia-toned childhood recollections because Broken Greek was not written by Paphides the Greek-Cypriot immigrant or Paphides the music critic, but Paphides the music lover. As intimate and ephemeral as the relationship between a listener and their music is, it is also a familiar shared experience. By grounding the book in this experience, he anchors readers who might otherwise be swept away by the barrage of unfamiliar references or disoriented by the world of 1970s Birmingham.

Paphides’s focus on the inner world of his childhood and his experience of music means that a good portion of the book is devoted to his thoughts and feelings. The events of the book’s ten years are riveting, but do not command seismic degrees of drama. It can be argued he should have covered more ground, like the histrionics of late adolescence. At times the level of detail felt excessive given the repetitiveness and banality of the school-going routine he chronicles, especially in the blow by blow accounts of schoolyard soccer matches. But the authentic retelling of a life is perhaps less about communicating the sequence of events which occurred, than it is about parsing what they meant to the subject. By that standard, Paphides has authored a faithful and insightful account of his early childhood.

But this begs the question – examining cultural eras populated by some of the most colourful public figures in recent memory, why should we care about the individual’s experience of music? Much ink has been spilt detailing the development of pop music and putting the lives of its icons under the microscope, rather than invoking them only as accessories to an individual’s bildungsroman. Yet, why is there still magic in Paphides’s worm’s eye view account?

In spotlighting the subjective experience of music, Paphides reveals how music is embedded in deeply personal realities. His most evocative writing on music is an act of imagination, rather than a dogmatic narration of the music’s factual provenance. He conjures these musicians from an age past with his childhood self’s vivid imagination, for instance asserting British pop group Racey’s Richard Gower’s “perpetually needy expression was somehow discernable merely by listening to his pleading delivery of the vocals.” Through these conjectures he locates the emotional core of the music, taking him closer to the heart of what earned artists like Bowie and The Clash pride of place in the pop pantheon for a generation of listeners than what a factual recapitulation could achieve.

Conversely, when Paphides fails to balance factual details and his emotional relationship to the music, his critique can come across as ponderous. The anecdotal nuggets are necessary intermissions for those not intrinsically enthused by the biographical minutiae of ABBA. My attention wavers when he jumps into two page long close readings of songs, though to his credit he is discerning about which songs he spotlights. His trenchant critique and droll asides are elevated in the moments when music and autobiographical elements intertwine, speaking uncannily to each other across time and space through the tinny speakers of the household radiogram.

But more than that, the unique, subjective experience of music Paphides hones in on is precisely what makes up a cultural era. A pop cultural moment is only as powerful as its personal resonance. The cultural significance of ABBA of the Sex Pistols doesn’t derive from the millions album sales or number of weeks spent at number one on the charts. The magic of the pop phenomenon is located in living rooms and record stores, school fields and radios. It is in the raucous schoolyard debates of U2 versus Echo & the Bunnymen, a needling sibling rivalry because this was your band, so obviously your younger brother couldn’t be a fan too, in the flash of illumination, a teenager in a bedroom, listening to what feels like the anthem of his life. So why should our understanding of cultural history be limited to the bird’s eye view, looking down from the top of the chart or across the rolling expanse of the broader musical narrative? Pop has always been the music of the people, the elastic boundaries of the genre constantly shifting in response to the audience it is written for, defined only by the singular ability to resonate throughout the population; the grand narrative of pop would be incomplete without the account of the listeners at its heart. Broken Greek is not an autobiography accessorised by music, it is a sliver of musical history itself.