J.M. Iacchei

In Part I of this blog series I introduced barkcloth, gave a brief historical and cultural overview, described methods of production, and concluded with the importance of conservation and preservation efforts. Part II continues with highlights from the treatment of the 12 pieces of barkcloth from the Cornell Costume and Textile Collection. “Less of you; more of my ancestors.” These were the words of guidance shared by a colleague when I inquired about treatment for this collection. I wanted to be certain that an appropriate level of treatment was provided without compromising the historic integrity of these ethnographic items. Because many of these pieces of cloth were oversized, they would need to be rolled both for final storage, and for transport to and from the digitization studio. This would mean needing the strength to withstand numerous rollings and unrollings during the imaging process, as well as afterwards in use in instruction and research.

“Less of you; more of my ancestors.” These were the words of guidance shared by a colleague when I inquired about treatment for this collection. I wanted to be certain that an appropriate level of treatment was provided without compromising the historic integrity of these ethnographic items. Because many of these pieces of cloth were oversized, they would need to be rolled both for final storage, and for transport to and from the digitization studio. This would mean needing the strength to withstand numerous rollings and unrollings during the imaging process, as well as afterwards in use in instruction and research.

In addition to this stability concern were the inherent causes of deterioration rooted in the items’ history, extending from the time of manufacture and the processes involved to use, and the environmental conditions of previous and present storage.

Before discussing the causes of deterioration, it is worth noting that some parts of the manufacturing process actually inherently strengthened the quality of the cloth produced. Steps taken during the pre-beating processes, and the nature of the beating and drying processes each involve aspects that facilitate the longevity of the cloth.The practice of soaking or steeping the bark for several hours prior to beating encourages a stronger and more flexible cloth. As a result of this process, bacteria and fungi from fermentation cause the plant cell wall material to break down, allowing the pectin and hemicelluloses that normally stabilize the cell walls of the living plant to solubilize and redistribute. Because of this redistribution, the resulting cloth is more flexible. The pectin and hemicelluloses that remain in place add strength to the fibers and consequently, also to the cloth.[1]

During beating, the grooves on the face of the beater spread the fibers and alter their parallel orientation to one that is angled and interlocking as well as allow excess water and air to escape. This interlocking, rather than parallel orientation, is stronger and less prone to lateral tears that most often occur parallel to the grain of the cloth’s fiber.[2] In the drying process, the barkcloth is stretched out in the sun. The high UV content of the tropical sun stunts the growth of micro-organisms.[3]

It is the following stages of decoration, use, and storage conditions that most contribute to deterioration. Just as environmental factors affect paper materials, mechanical stresses, light exposure, fluctuations in relative humidity, biological agents, and pollutants each contribute to further deterioration of barkcloth; the effects of which can be seen in color changes, staining, insect damage, mold growth and weakening of fibers.

The traditional methods of island storage were not preservation-minded. Typically, large pieces of barkcloth were stored in rolls among the rafters of the home, often in areas affected by cooking smoke. While the cooking fire kept the cloth dry and free of mold and the aldehydes in the wood smoke acted as a preservative against bio-deterioration, the exposure to smoke allowed for the collection of soot, an environmental pollutant which will overtime lead to deterioration.[4]

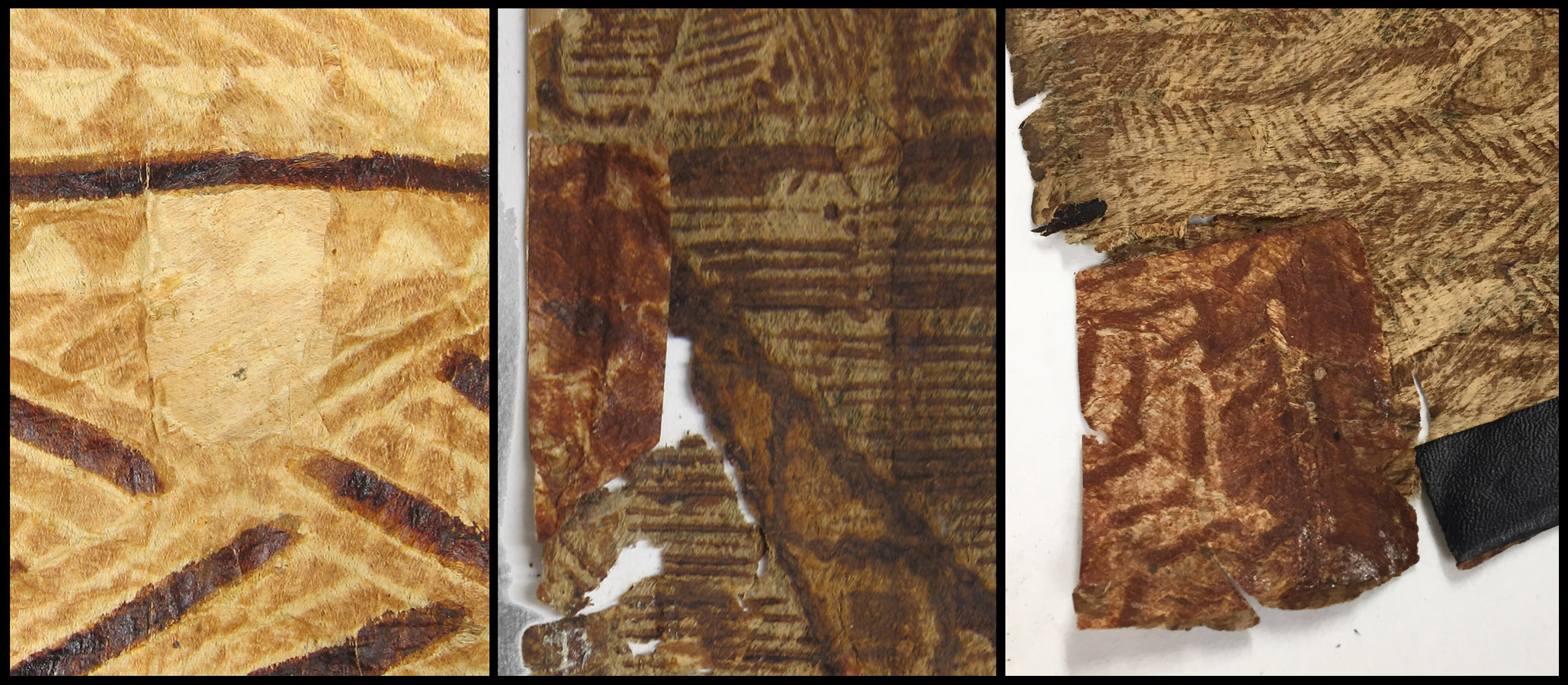

The dyes, pigments, resins, gums, paints, and oils used to decorate and finish barkcloth over time can deteriorate – becoming faded, brittle, and flaking. Consequently, the cloth below the colored area will also become brittle and stiff, causing breaking, tearing along folds, or separating along the grain, leaving holes.[5]

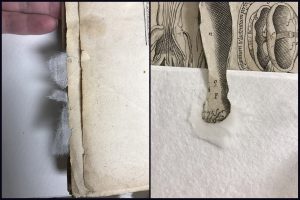

In this collection, the main concerns were the stubborn folds incurred from previous storage, and the embrittlement of the dyes used to apply designs to the cloth.

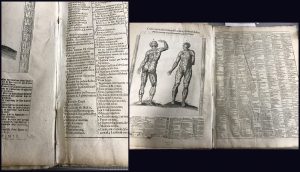

Eleven of the twelve items were stored together over long periods of time in a box resulting in stubborn horizontal and vertical folds. The stubborn folds were a concern both for quality of image capture and for compression overtime which leads to tears.

Overtime, dyes begin to become brittle and flake, and/or cause the fibers below to become brittle resulting in loss.

Numerous small lateral splits in the barkcloth, areas of loss, and areas of potential loss presenting instability needed to be addressed before these items could be safely transported on a roll to the digitization studio. Before these concerns could be remedied, surface soil that would contribute to further deterioration or that would otherwise embed into the fiber of the cloth when moisture was introduced during humidification first needed to be removed, and the folds reduced.

Each piece of barkcloth was vacuumed through a screen with a Nilfisk HEPA vacuum, lightly humidified to relax the fibers of the cloth, and dried under weight. Very light weight was used so as to not affect the inherent textured quality of the cloth- just enough to reduce the stubborn folds.

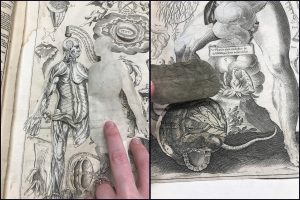

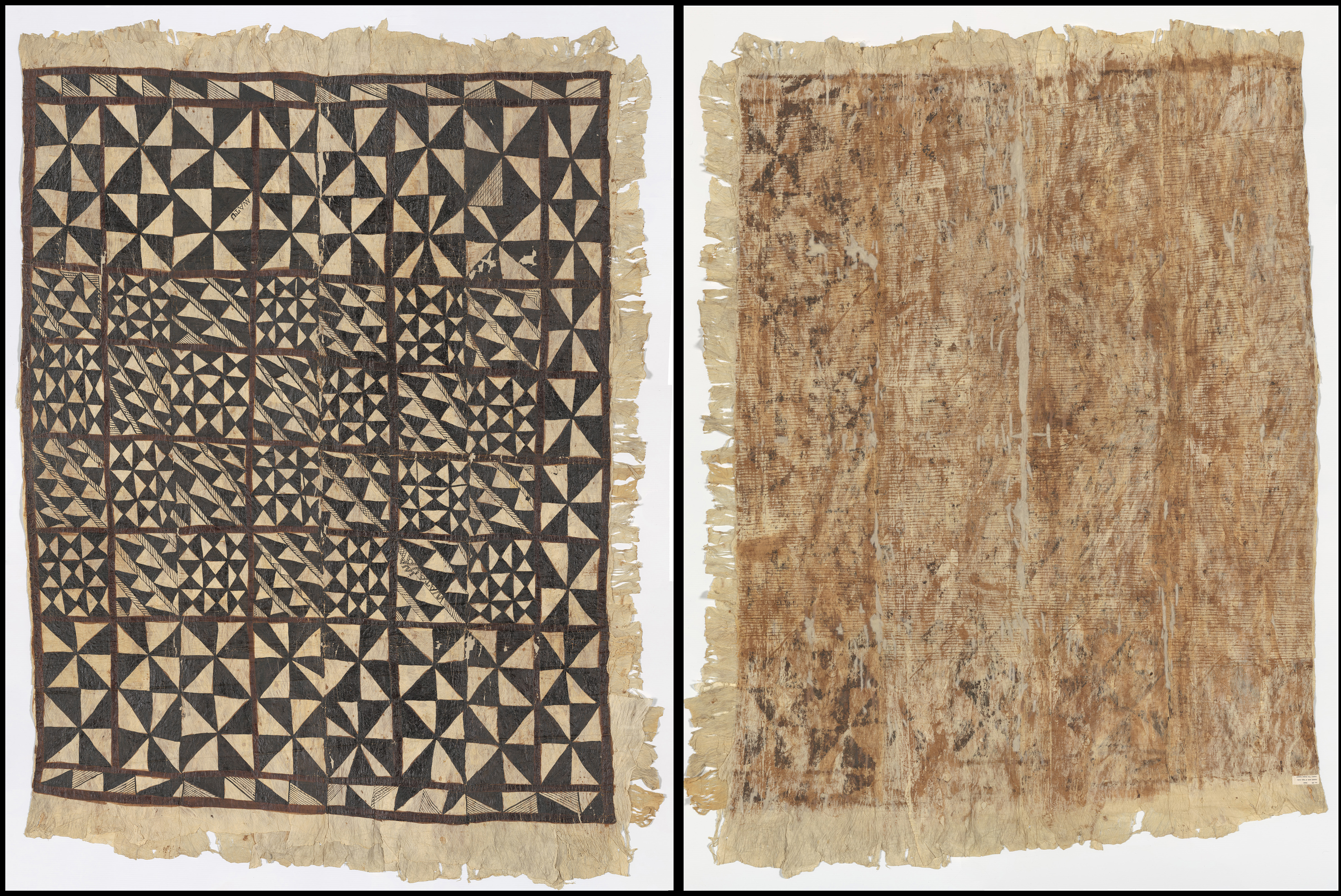

(Left) Holes that occurred at the time of manufacture during beating were patched with small pieces of barkcloth. (Center and Right) Similarly, later repairs were made with recycled pieces of barkcloth. In these instances, the previous repair was left. The black tape shown in the rightmost image above however, was removed.

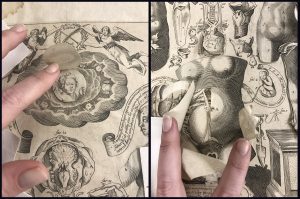

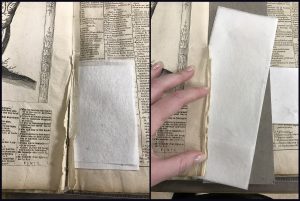

Areas of instability, like the ones shown below, were addressed by mending with a stable Japanese tissue of an appropriate tone and weight (to blend with the natural color and thickness of the cloth). Wheat starch paste was chosen as an adhesive. In previous testing, it proved to be the most compatible with the texture and finish of the cloth. Other adhesives, methyl cellulose for example, seemed to leave a shiny finish.

Significant tears and loss required a different approach. The barkcloth shown below had a central vertical tear extending nearly the entire length (just under 8 feet). The dyes were brittle and flaking; the cloth on either side of the tear was also brittle, shredded, and mangled. Temporary reversible bridge mends were applied on the front to ensure that the design was aligned correctly. The cloth was then rolled, unrolled to have the underside face up, and mended on the verso (back).

(Left) Vertical tear extending nearly the full length of the cloth; (Center:top) Aligning areas along the tear prior to mending on the verso; (Center bottom and right) Temporary reversible bridge mends to hold cloth in position

Once treated, each item could be safely transported for digitization. Each side of each item required multiple shots (12-15 shots per side) that would then be stitched together using the camera software.

Simon Ingall, Digital Imaging Assistant, expertly facilitates the maneuvering and successful image capture of the oversized pieces of barkcloth.

Ideally, if space allows, barkcloth should be stored flat. Among this collection, those that fit in folders were stored flat in archival paper folders in flat file map cases. The remaining oversized pieces were rolled on archival tubes covered with ethofoam (for cushioning) and a Mylar cover (a barrier between the barkcloth and the ethofoam). The barkcloth was rolled face up with Hollytex interleaving (spun polyester web), labeled with thumbnail image and catalogue information, and returned to The College Human Ecology, Department of Fiber Science and Apparel Design for use in instruction and research.

While this treatment included practices commonly used in paper conservation treatments – utilizing the same materials and stabilization techniques, working with laminate structures, and navigating over-sized items there are inherently unique qualities about barkcloth that required research, collaboration, and skills from allied conservation specialties. We are very grateful to our international colleagues at The Smithsonian Institution, Te Papa Museum, NZ, Bishop Museum, HI, and University of Glasgow for sharing their knowledge and expertise that only comes from the experience of working directly with these materials.

While this treatment included practices commonly used in paper conservation treatments – utilizing the same materials and stabilization techniques, working with laminate structures, and navigating over-sized items there are inherently unique qualities about barkcloth that required research, collaboration, and skills from allied conservation specialties. We are very grateful to our international colleagues at The Smithsonian Institution, Te Papa Museum, NZ, Bishop Museum, HI, and University of Glasgow for sharing their knowledge and expertise that only comes from the experience of working directly with these materials.

Below is a short video highlighting the treatment process of these items:

[1] Rowena Hill, “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea: materials, production and conservation,” in Barkcloth: Aspects of preparation, use, deterioration, conservation and display, ed. Margot M. Wright (London: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2001), 33.

Due to the partial fermentation that occurs “activity from invading bacteria and fungi acquired during wetting and soaking, leads to a partial breakdown of the cell wall material helping to liberate pectin and hemicelluloses which normally cement the cells together ‘in vivo.” Thus dispersed, some of these binding chemicals get washed away, reducing the overall stiffness of the cloth. Those which remain ‘in situ’ help to thicken the fibers and bond them together in their newly aligned positions thereby strengthening the cloth.”

[2] Hill, “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea: materials, production and conservation,” 34.

[3] Hill, “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea: materials, production and conservation,” 35.

[4] Hill, “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea: materials, production and conservation,” 35.

[5] Hill, “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea: materials, production and conservation,” 41.