Michele Hamill

Due to the rise of digital photography, photographs are being shared faster and in unprecedented volume than ever before. To learn more about your digital photographs, this Library of Congress resource is a good place to start.

Due to the rise of digital photography, photographs are being shared faster and in unprecedented volume than ever before. To learn more about your digital photographs, this Library of Congress resource is a good place to start.

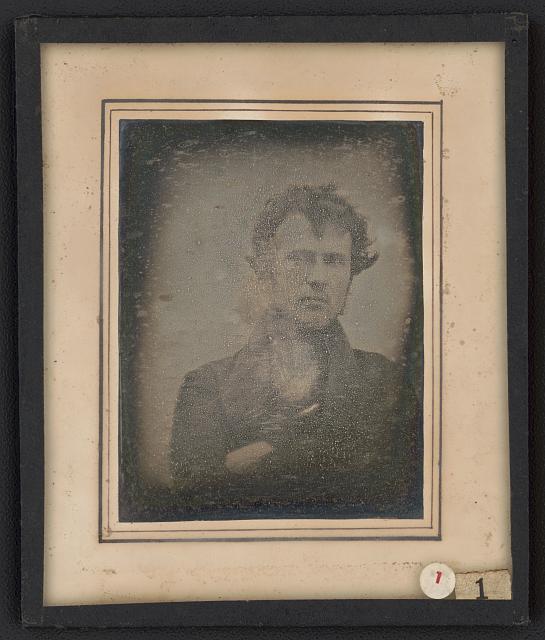

Some credit the first selfie to Robert Cornelius who took a daguerreotype self-portrait in October, 1839. This image, courtesy of The Library of Congress, is believed to be the earliest extant American portrait. Learn more about the fascinating effort currently underway to document Cornelius’ photographs here.

Some credit the first selfie to Robert Cornelius who took a daguerreotype self-portrait in October, 1839. This image, courtesy of The Library of Congress, is believed to be the earliest extant American portrait. Learn more about the fascinating effort currently underway to document Cornelius’ photographs here.

In addition to the plethora of digital photographs, family collections include prints, snap-shots, and studio portraits that form the pictorial history of generations of family members. Let’s take a look today at some of the types of photographs in family collections. (And, by the way, an interior closet on the main floor of your home, is a great place to store your family photographs since it tends to maintain a stable temperature and humidity.)

A daguerreotype (1839-1865), like the Cornelius self-portrait, is a treasure in a family collection. It is one of the earliest types of photographs and was most popular from the early 1840s to 1860. Daguerreotypes are comprised of a silver-coated copper plate housed in a sealed package behind glass. The sealed package sits in a protective hinged case made of wood covered by leather, cloth, or paper. Daguerreotypes have a highly polished, mirror-like surface and are often hand-colored with pigments. They are complex, unique objects that deserve special care.

A daguerreotype (1839-1865), like the Cornelius self-portrait, is a treasure in a family collection. It is one of the earliest types of photographs and was most popular from the early 1840s to 1860. Daguerreotypes are comprised of a silver-coated copper plate housed in a sealed package behind glass. The sealed package sits in a protective hinged case made of wood covered by leather, cloth, or paper. Daguerreotypes have a highly polished, mirror-like surface and are often hand-colored with pigments. They are complex, unique objects that deserve special care.

An Ambrotype, most popular in the late 1850s, is another type of cased photograph, but they differ from daguerreotypes because the emulsion containing the silver image is coated on a sheet of glass rather than metal. Ambrotypes were a popular means of portraiture and were an economical alternative to daguerreotypes, but were largely replaced by tintypes, which were even cheaper, faster, and easier.

An Ambrotype, most popular in the late 1850s, is another type of cased photograph, but they differ from daguerreotypes because the emulsion containing the silver image is coated on a sheet of glass rather than metal. Ambrotypes were a popular means of portraiture and were an economical alternative to daguerreotypes, but were largely replaced by tintypes, which were even cheaper, faster, and easier.

Tintypes were popular from the start of the Civil War until the 20th century. They were less expensive than cased photographs, and they were made on coated iron, not tin. They were placed in paper mats or albums, or left loose, as in this example. Tintypes are most commonly found in the carte-de-visite size (approx. 2 ½” × 4″ to 4 ¼”). Because they often have no protective covering, tintypes are frequently dented, scratched, or rusted.

Tintypes were popular from the start of the Civil War until the 20th century. They were less expensive than cased photographs, and they were made on coated iron, not tin. They were placed in paper mats or albums, or left loose, as in this example. Tintypes are most commonly found in the carte-de-visite size (approx. 2 ½” × 4″ to 4 ¼”). Because they often have no protective covering, tintypes are frequently dented, scratched, or rusted.

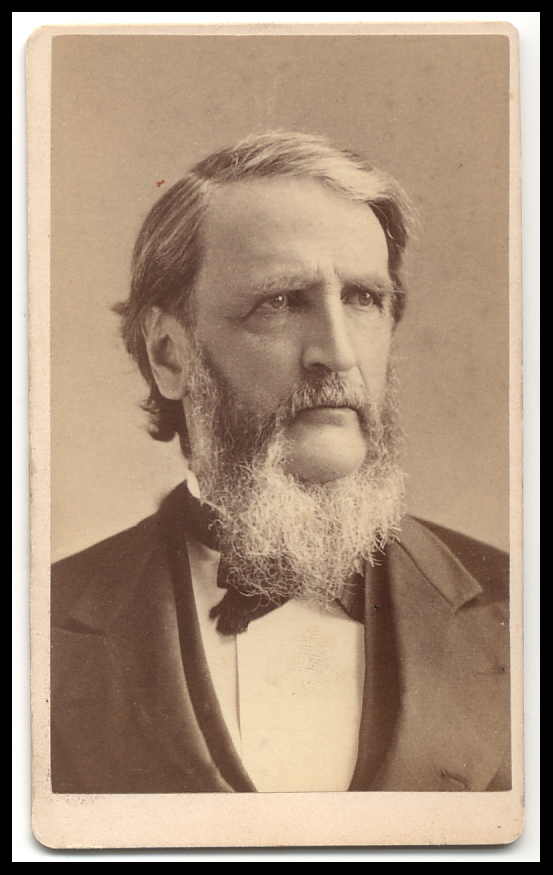

Albumen photographs were most popular from 1850-c. 1895. They have a silver image in an albumen emulsion coated on thin paper, like this cabinet card portrait. Albumen, the white part of an egg, was the most common emulsion for 19th-century prints. To make them studier, most albumen photographs were mounted to a secondary support or card. Cabinet refers to the format used to present the image, not the photographic process used to create the image. Cabinet cards measure approximately 4 ½ by 6 ¼ inches and often have information about the photographer or studio which is useful for dating and identifying images. Albumen was gradually superseded by gelatin and collodion printing-out papers around 1885.

Albumen photographs were most popular from 1850-c. 1895. They have a silver image in an albumen emulsion coated on thin paper, like this cabinet card portrait. Albumen, the white part of an egg, was the most common emulsion for 19th-century prints. To make them studier, most albumen photographs were mounted to a secondary support or card. Cabinet refers to the format used to present the image, not the photographic process used to create the image. Cabinet cards measure approximately 4 ½ by 6 ¼ inches and often have information about the photographer or studio which is useful for dating and identifying images. Albumen was gradually superseded by gelatin and collodion printing-out papers around 1885.

Another format of the albumen print is the carte-de-visite – which, at 4 ¼ by 2 ½ inches, is smaller than a cabinet card and about the size of calling cards or modern-day business cards. They were an enormously popular form of presentation for 19th-century portraits.

Another format of the albumen print is the carte-de-visite – which, at 4 ¼ by 2 ½ inches, is smaller than a cabinet card and about the size of calling cards or modern-day business cards. They were an enormously popular form of presentation for 19th-century portraits.

Printed-out photographs, such as this 19th-century cabinet portrait, have a warm brown-purple image rather than a neutral tone, because the silver image was formed from “printing-out” in daylight, not from chemical development. Printed-out photographs can look similar to albumen prints but have a major difference. Printed-out photographs have a very white baryta layer between the paper support and the emulsion. Emulsions for printed out photographs can be either gelatin or collodion. Many glossy collodion prints exhibit a subtle iridescent effect on their surface.

Printed-out photographs, such as this 19th-century cabinet portrait, have a warm brown-purple image rather than a neutral tone, because the silver image was formed from “printing-out” in daylight, not from chemical development. Printed-out photographs can look similar to albumen prints but have a major difference. Printed-out photographs have a very white baryta layer between the paper support and the emulsion. Emulsions for printed out photographs can be either gelatin or collodion. Many glossy collodion prints exhibit a subtle iridescent effect on their surface.

Cyanotypes, most popular from 1880 to the 1920s, are readily identified by their distinctive blue color, which results from using iron rather than silver as the image material. Family collections often contain cyanotypes, because their low cost and easy processing appealed to amateur photographers.

Cyanotypes, most popular from 1880 to the 1920s, are readily identified by their distinctive blue color, which results from using iron rather than silver as the image material. Family collections often contain cyanotypes, because their low cost and easy processing appealed to amateur photographers.

Crayon portraits, popular from the 1880s to the 1920s, were enlargements that could be life-size. They were made using a weak photographic base extensively hand-colored with pastels and charcoals, among other artist materials. Crayon enlargements were sometimes mounted to cloth and often placed in decorative frames. This 19th-century crayon enlargement shows the line of discoloration in the upper right corner where the cracked glass of an old frame let in atmospheric pollutants. It also shows overall darkening from damaging light exposure. The edges were protected from light exposure by the frame. Crayon enlargements can be brittle and are best stored in shallow boxes.

Crayon portraits, popular from the 1880s to the 1920s, were enlargements that could be life-size. They were made using a weak photographic base extensively hand-colored with pastels and charcoals, among other artist materials. Crayon enlargements were sometimes mounted to cloth and often placed in decorative frames. This 19th-century crayon enlargement shows the line of discoloration in the upper right corner where the cracked glass of an old frame let in atmospheric pollutants. It also shows overall darkening from damaging light exposure. The edges were protected from light exposure by the frame. Crayon enlargements can be brittle and are best stored in shallow boxes.

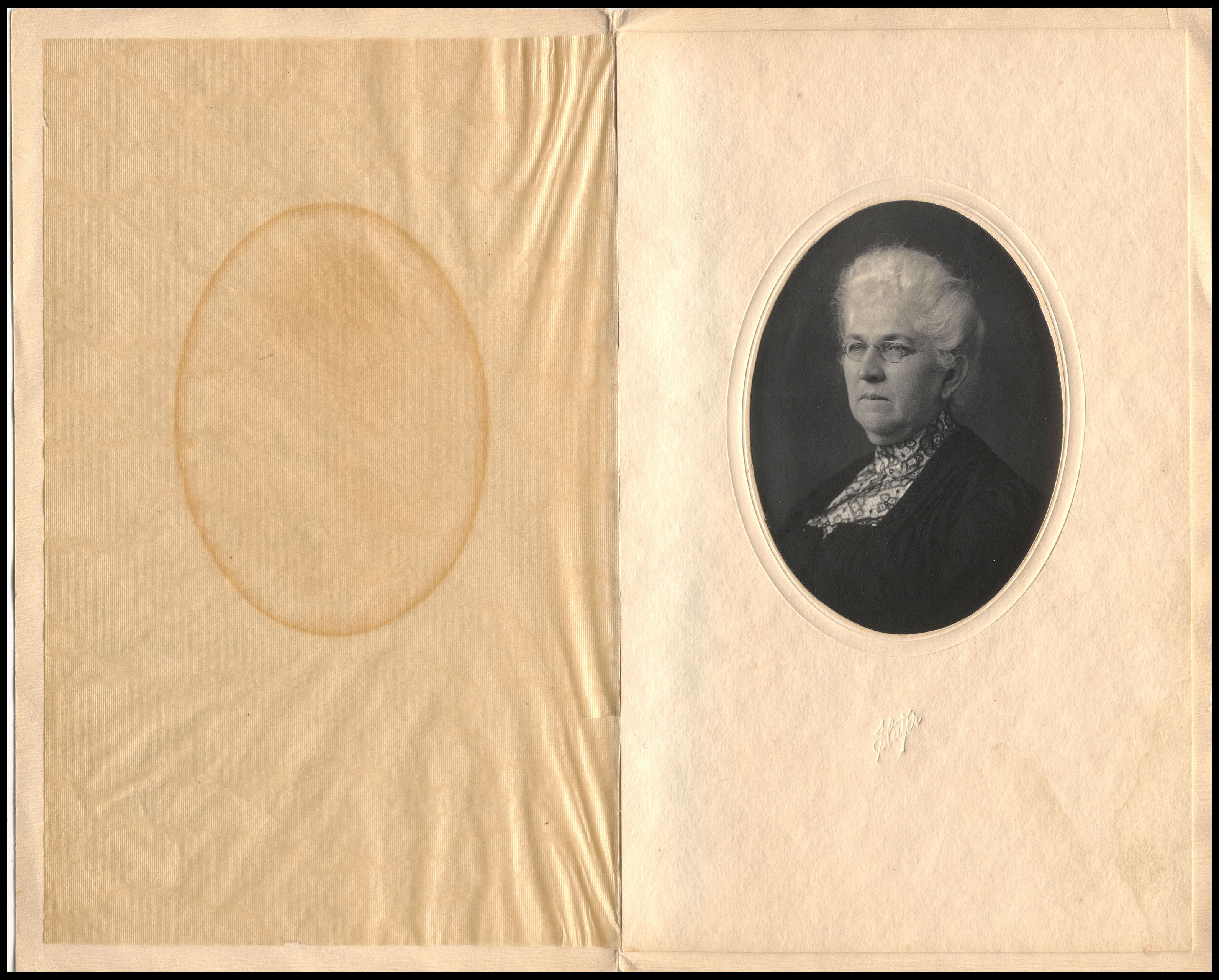

Platinum prints (1880-1930), in which platinum and not silver is the image material, have rich details, a velvety black color, and good image stability with no fading. Platinum prints were often used for studio portraits presented in a folder format. The characteristic image transfer of a ghost-print to the paper folder helps identify this print as platinum.

Platinum prints (1880-1930), in which platinum and not silver is the image material, have rich details, a velvety black color, and good image stability with no fading. Platinum prints were often used for studio portraits presented in a folder format. The characteristic image transfer of a ghost-print to the paper folder helps identify this print as platinum.

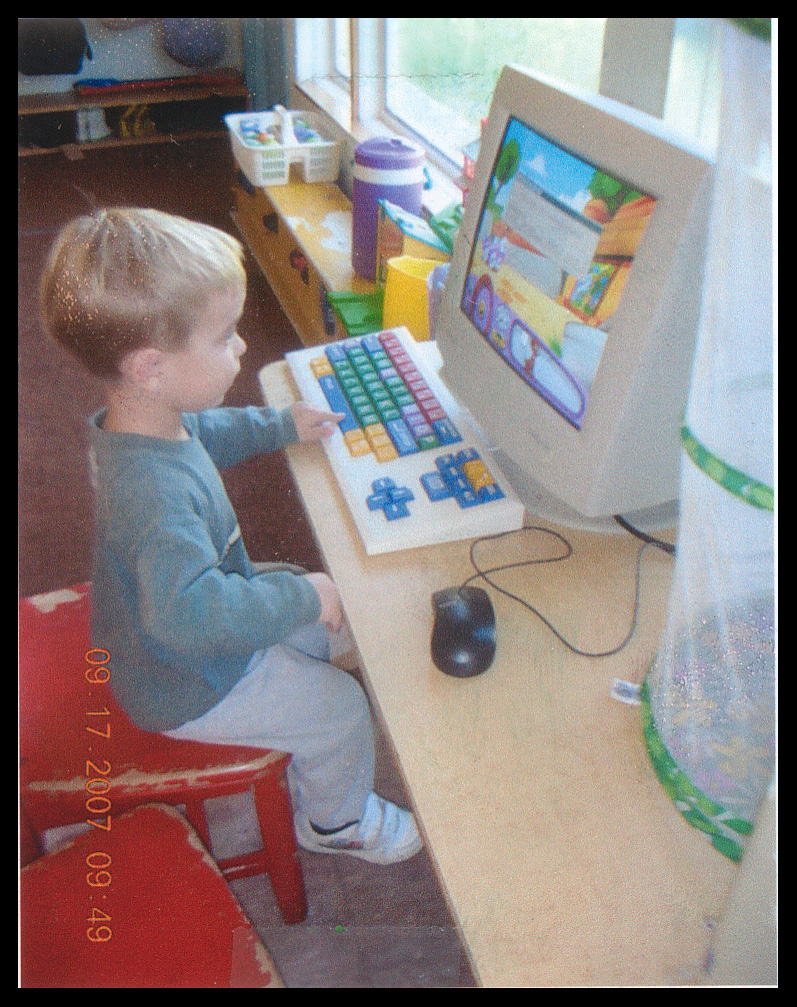

This 20th-century, silver gelatin, black-and-white snapshot shows one of photography’s popular themes: children. People, pets, weddings, and vacations are common subjects. The image is made of silver suspended in a gelatin emulsion, the most common emulsion used for photographic prints in the 20th century. Remnants of the black paper corners are not harmful and can remain. This wedding portrait was well-processed and remains in superb condition.

This 20th-century, silver gelatin, black-and-white snapshot shows one of photography’s popular themes: children. People, pets, weddings, and vacations are common subjects. The image is made of silver suspended in a gelatin emulsion, the most common emulsion used for photographic prints in the 20th century. Remnants of the black paper corners are not harmful and can remain. This wedding portrait was well-processed and remains in superb condition.

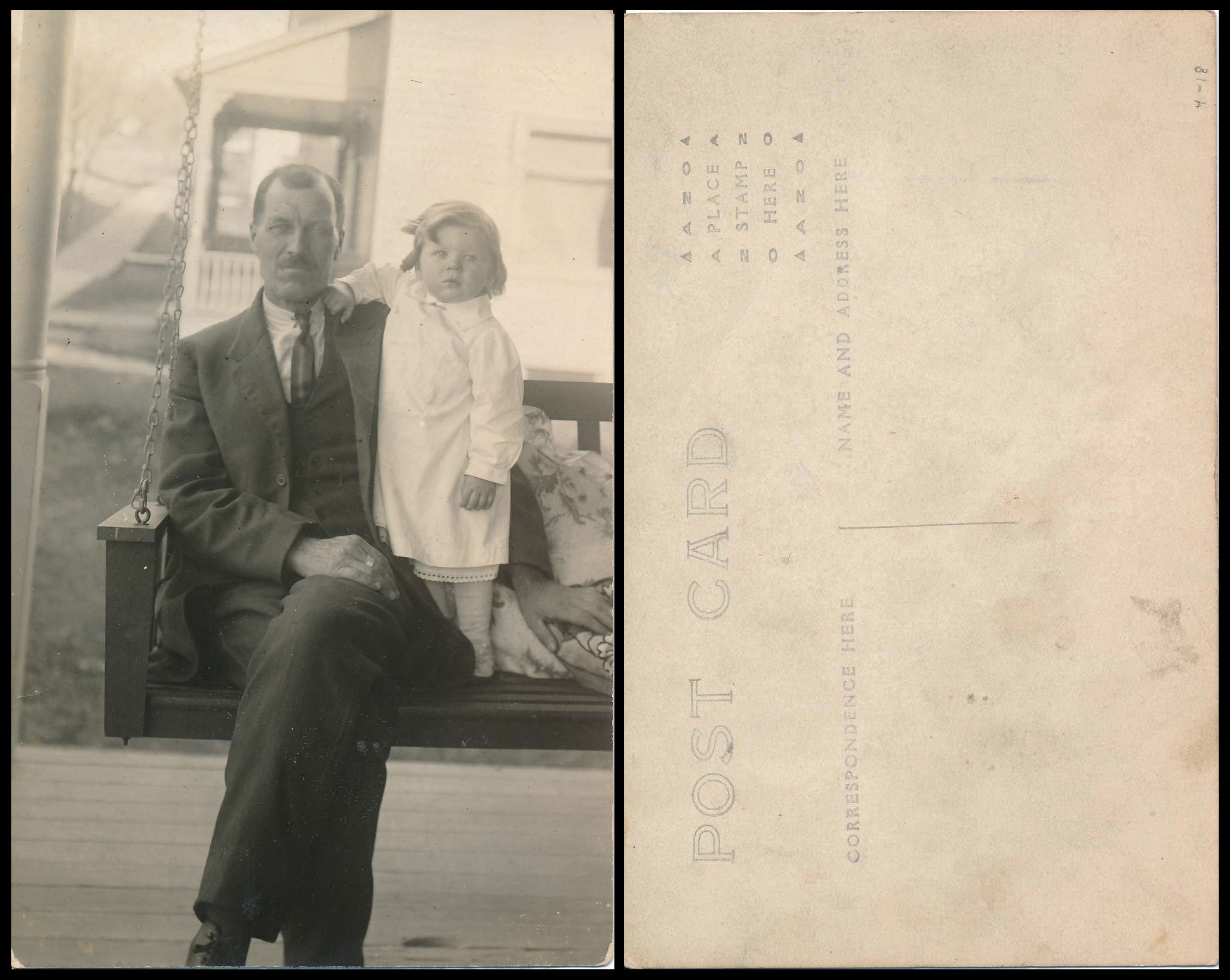

Most postcards were made using ink printing process, like lithography. However some postcards are true photographs, or “real photo postcards”, with a postcard back, such as this silver gelatin postcard. There are many resources to learn more about the history of postcards and for dating the stamp box found on real photo postcards.

Most postcards were made using ink printing process, like lithography. However some postcards are true photographs, or “real photo postcards”, with a postcard back, such as this silver gelatin postcard. There are many resources to learn more about the history of postcards and for dating the stamp box found on real photo postcards.

Sepia-toned silver gelatin photographs, like this portrait in its complementary brown presentation folder, were created by toning 20th-century black-and-white photographs to a warm brown or “sepia” reminiscent of the 19th century. Sepia-toned photographs are very stable and show little image deterioration or fading. Because the brown folder is the original presentation for this photograph and is not causing damage, the folder and photograph can remain together.

Sepia-toned silver gelatin photographs, like this portrait in its complementary brown presentation folder, were created by toning 20th-century black-and-white photographs to a warm brown or “sepia” reminiscent of the 19th century. Sepia-toned photographs are very stable and show little image deterioration or fading. Because the brown folder is the original presentation for this photograph and is not causing damage, the folder and photograph can remain together.

Hand-colored silver gelatin photographs, like this example from the 1940s, were an early attempt to bring color to black-and-white photographs using artist’s materials. For this 1940’s print, dyes (which readily fade) were used to color the image.

Hand-colored silver gelatin photographs, like this example from the 1940s, were an early attempt to bring color to black-and-white photographs using artist’s materials. For this 1940’s print, dyes (which readily fade) were used to color the image.

Color photographs formed the largest segment of the snapshot market, beginning in the 1960s. Dyes used in color prints are prone to fading, exacerbated by light and heat. Early color photographs often show fading, or a shift in color, where one color predominates. Improvements in the 1990s resulted in longer-lasting color images. These 3 color photographs show fading (left), color shift (middle), and modern color (right).

Color photographs formed the largest segment of the snapshot market, beginning in the 1960s. Dyes used in color prints are prone to fading, exacerbated by light and heat. Early color photographs often show fading, or a shift in color, where one color predominates. Improvements in the 1990s resulted in longer-lasting color images. These 3 color photographs show fading (left), color shift (middle), and modern color (right).

Polaroids, most popular in the 1970s and 1980s, often have a distinctive white border as in this example. They were a form of instant photography with do-it-yourself appeal because they did not require processing in a darkroom. Polaroids are one-of-a-kind images, because no negative is created in the process, so they may be unique images in a family collection. They can suffer from stability problems, including fading, cracking, and delamination.

Polaroids, most popular in the 1970s and 1980s, often have a distinctive white border as in this example. They were a form of instant photography with do-it-yourself appeal because they did not require processing in a darkroom. Polaroids are one-of-a-kind images, because no negative is created in the process, so they may be unique images in a family collection. They can suffer from stability problems, including fading, cracking, and delamination.

Digital prints can be made using a variety of processes, including ink-jet (the most common printer used at home), electrophotography (office color printers), digital photo processors (used in many photo labs to print snapshots), and dye sublimation (used to make prints at photo kiosks). The stability of the digital prints depends on the process used to make them, the combination of the inks or dyes and paper used, and how they are stored and handled.

Digital prints can be made using a variety of processes, including ink-jet (the most common printer used at home), electrophotography (office color printers), digital photo processors (used in many photo labs to print snapshots), and dye sublimation (used to make prints at photo kiosks). The stability of the digital prints depends on the process used to make them, the combination of the inks or dyes and paper used, and how they are stored and handled.

Here are some great resources for more information about family photographs:

The Graphics Atlas is a sophisticated resource that presents a unique, object-based approach for the identification and characterization of prints and photographs.

http://www.graphicsatlas.org

The Preservation Self-Assessment Program (PSAP) from the University of Illinois Library has a great format ID guide:

https://psap.library.illinois.edu/format-id-guide

And from the Getty: The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes

http://www.getty.edu/…/publicat…/pdf_publications/atlas.html