On this episode of the Migrations: A World on the Move podcast, we learn from Professor Kurt Jordan and Laiken Jordahl about dispossession: what it is and how it is affecting Indigenous people, wildlife, and ecosystems. Jordan works in the Finger Lakes region of New York, studying the effects of institutions like Cornell on the Indigenous populations of the region. Jordahl is an activist and ally helping to bring awareness to the harm caused by wall construction at the U.S.-Mexico border.

On March 10, 2021, Cornell University Associate Professor Kurt A. Jordan, who also directs the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) and chairs AIISP’s Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Committee, spoke to faculty, staff, and students at Cornell AgriTech (in Geneva, New York) and Cornell’s School of Integrated Plant Science (SIPS). His presentation focused on the necessity for land issues to be locally-focused, noting that Cornell AgriTech sits on the exact location as the Onöndowa’ga:’ (Seneca Iroquois) town of Kanadesaga. Kanadesaga was destroyed by the American Sullivan-Clinton Expedition in September 1779, a campaign that Haudenosaunee communities and many scholars consider to have been genocidal in intent and outcome. To address this history and Cornell’s continuing benefit from the Geneva campus, AgriTech needs to develop communications and relations with present-day Onöndowa’ga:’ communities in New York State, Ontario, and Oklahoma. Jordan also briefly discusses the current state of research, community outreach, and plans for restitution surrounding Cornell’s entanglements with Indigenous dispossession, both locally and continent-wide due to its engagement with the Morrill Land Grant College Act of 1862.

The following is taken from the Present Value podcast, founded in fall 2017 by two Cornell MBA students. This episode was originally released on February 22, 2021.

In this episode, with host María Castex, Professor Jon Parmenter discusses his research on indigenous dispossession and Cornell University’s legacy as a land grant institution. In October of 2020, Parmenter wrote a blog post titled Flipped Scrip, Flipping the Script: The Morrill Act of 1862, Cornell University, and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Indigenous Dispossession. This episode discusses the Morrill Act and its further implications in detail, along with the degree to which we must confront this history and engage in discourse and the broader process of redress.

The podcast episodes are researched, written, edited, and sound engineered by the MBA student producers. Each episode has one host, supported by a student production team.

The audio of this podcast has been removed and it appears no archive was made. Please refer to the transcript below for the content of the episode.

Transcript

Read the full transcript here.

Speakers

Jon Parmenter, associate professor of history at Cornell University

María Castex ’21, Cornell MBA student

Kimberly Fuqua ’21, Cornell MPA student

The following is taken from The Humanities Pod, funded by The Society for the Humanities at Cornell originally posted to their website on January 21, 2021. Informal conversations with Society Fellows, Cornell Faculty, community collaborators, and special guests shine a light on some of the new work, the current conversations, and the latest ideas of humanists at and around Cornell.

This podcast further addresses the relationship between Cornell University’s founding in 1862 under the Morrill Act and the United States’ prior dispossession of Indigenous nations’ homelands that provided the “public lands” utilized to fund land-grant colleges and universities.

Speakers

Jon Parmenter, associate professor of history at Cornell University

Paul Fleming, Taylor Family Director of the Society for the Humanities

Michael Witgen, professor and former director of Native American Studies at the University of Michigan

Transcript

Table of Contents

Cornell and the Morrill Act: 120 Years of Land Acquisition

by Jacobi Kandel, Maggie Lam, and Zelazzie Zepeda

October 2023

Our Goals and Methods: How the Cornell University & Indigenous Dispossession Committee Determined which Present-Day Nations and Communities have been Affected by Cornell’s Past and Present Land Manipulations

by Kurt A. Jordan, Dusti C. Bridges, and Troy A. Richardson

October 17, 2023

Press Release: Cornell University’s Land Grab Impacts 251 Tribes

by Leslie Logan

October 7, 2023

Good Intentions are Not Good Relations: Grounding the Terms of Debt and Redress at Land Grab Universities

Article published in ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 22(3).

by Meredith Alberta Palmer

June 21, 2o23

The 2022 Kops Freedom of the Press Lecture – Land-Grab Universities: Recent Past, Present and Future of Indigenous Dispossession

Video of recorded lecture given by Tristan Ahtone and Dr. Robert Lee hosted by Cornell University’s American Studies Program and recorded by eCornell.

September 13, 2022

Land-Grant Beneficiaries Need to Finally Right Wrongs

Letter to the Editor for The Chronicle of Higher Education

August 30, 2022

Assessing Cornell University’s response to recent revelations concerning the origins of revenues obtained from the Morrill Act of 1862

by Professor Jon Parmenter

August 17, 2022

My backyard, equity concerns, and Land Grant truth-telling

by Dr. Charles Geisler for The Natural Farmer

July 27, 2022

Debts, ethics, and redress: Moving Land Grab University work forward

by Dr. Meredith Alberta Palmer (Six Nations Tuscarora) as a part of AIIS 6010: Speaker Series

September 10, 2021

Letter to Dr. Pollack on Cornell’s Morrill Act Lands: One Year Anniversary

by Dr. Fred Wien and Dr. Charles Giesler

September 8, 2021

Migrations: A World on the Move Podcast – Dispossession

by Professor Kurt Jordan and Laiken Jordhal for Migrations: A World on the Move

June 17, 2021

Cornell’s Relationship to Indigenous Dispossession: Geneva and Beyond

by Professor Kurt Jordan for Cornell AgriTech Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee

March 10, 2021

A Land Grant University: Cornell’s Legacy

by Professor Jon Parmenter for the Present Value podcast

February 22, 2021

Indigenous Dispossession and the Founding of Cornell: Part 2 with Michael Witgen

by Professor Jon Parmenter and Professor Michael Witgen for The Humanities Pod

January 21, 2021

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s notoriety in Indian country and Cornell’s campus landscape

by Dr. Meredith Alberta Palmer

January 4, 2021

Indigenous Dispossession and the Founding of Cornell: Part 1 with Jon Parmenter

by Professor Jon Parmenter for The Humanities Pod

December 14, 2020

Cornell Administration revises text on webpage for Cornell’s Land Grant Mission

December 10, 2020

Indigenous People’s Day Panel on Indigenous Dispossession Project

by The American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program

December 2, 2020

From Bad to Worse: Ithaca Common Council Rewrites History to the Detriment of Us All

by Professor Jon Parmenter

October 20, 2020

Petition to Support NAISAC Demands

by the Native American & Indigenous Students at Cornell

October 14, 2020

Flipped Scrip, Flipping the Script: The Morrill Act of 1862, Cornell University, and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Indigenous Dispossession

by Professor Jon Parmenter

October 1, 2020

Breaking the Silence on Cornell’s Morrill Act Lands

by Dr. Fred Wien and Dr. Charles Geisler

September 29, 2020

Discussion of Cornell University as a Land-Grab University – Professor Eric Cheyfitz

by Professor Eric Cheyfitz

September 28, 2020

The Cornell Morrill Act Lands Interactive Map

by Dr. David Strip

August 26, 2020

Cornell University: The erasure of memory

by Professor Eric Cheyfitz

August 26, 2020

Cornell: A “Land-Grab University”?

by Professor Kurt Jordan

July 29, 2020

by Dr. Meredith Alberta Palmer

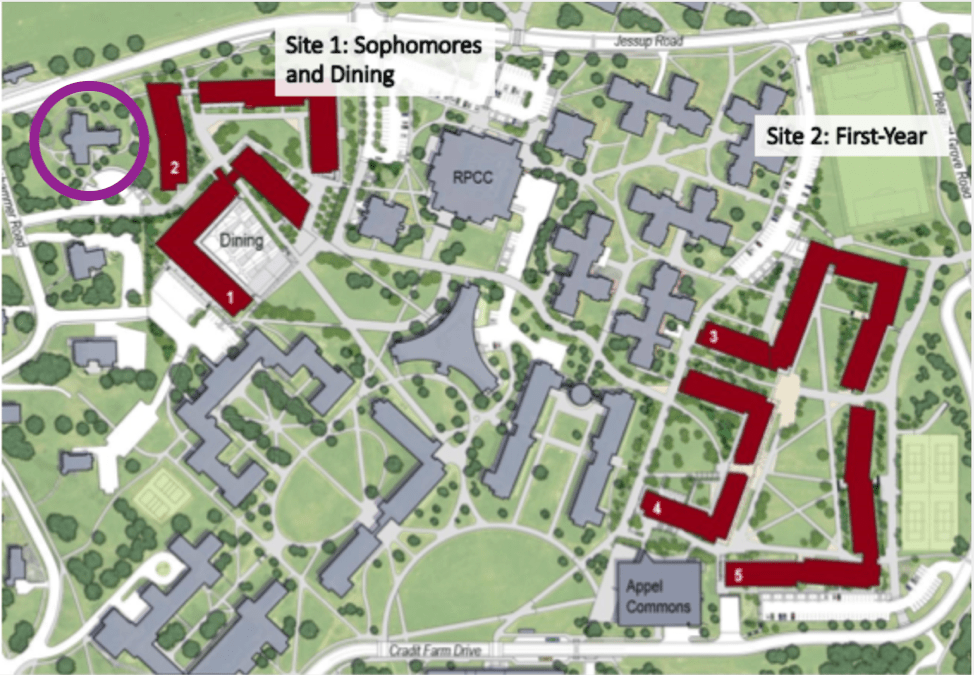

After Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away on September 18th, 2020, Cornell University committed to naming one of five new dorm buildings located in the North Campus Residential Expansion (NCRE) currently under construction, after her. Naming a building after Justice Ginsburg is an unsettling choice for anyone familiar with her harmful record regarding Indigenous nations and their legal treaties with the United States.

The new dorm buildings are the ones marked in red, at Site 1 and 2 in the map below. Just to the west of Site 1 sits the Native American residence hall Akwe:kon, on the map delineated with a purple circle. In Kanienkehaka, the language of the Mohawk people, Akwe:kon means “all of us.” Akwe:kon is the first university residence hall in the country dedicated to Native American students, communities, and scholarship, and is open to all students. It opened in 1991, and continues to house 35 undergraduate students, and to host Indigenous community and academic events. Since the announcement that a dorm building may be named after Justice Ginsburg, many in the community of Indigenous scholars and Native American studies academics at Cornell have been reckoning with this proposal, and working to assure that at the very least this Ginsburg Dorm will not be the one that now towers above Akwe:kon.

What might it mean for a new dorm building to be named after Justice Ginsburg? A building named for an individual who is so widely recognized transforms it into a space of memory. The university campus is a social and institutional landscape, and those who work and live within it draw identity and a sense of belonging—or conversely a sense of being out of place—from those memorializations. Whose memories count and are chosen to live within the design of campus landscapes is a question of power and notice. Regarding the proposed Ginsburg dedication and the one for Toni Morrison, Cornell President Martha Pollack stated that the university wants to “create a memorial that would be seen by, and have its doors open to, ‘any person’ at Cornell.” Any Indigenous student, staff, or faculty member—currently underrepresented at Cornell—who is from one of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s six nations (Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, Mohawk, Seneca, and Tuscarora), or who is Navajo, Chickasaw, Paiute, Shoshone, Potawatomi, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, or Kiowa, will likely know Ginsburg as a direct adversary to their Indigenous nations and their people. She instantiated this negative legacy in the harsh, anti-Indigenous language used in her court opinions dealing with Indian law cases affecting all the specific tribes here listed directly, and more in the precedent set by these deleterious court cases.

One of the most devastating and vexing decisions she wrote occurred merely 15 years ago regarding Oneida lands in New York State, just 1.5 hours northeast of Cornell’s campus. This 2005 Supreme Court case, City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, denied the right of the Oneida Nation of New York (ONNY) to reinstate their sovereign rights on parcels of land claimed to be part of the City of Sherrill, NY. In 1985 it had been determined by the US Supreme Court that over 6 million acres of Haudenosaunee land had been appropriated by New York illegally around the turn of the 18th century, including these specific parcels which had been illegally appropriated in 1805 and 1807. The Oneida Nation of New York then purchased these parcels back in the late 1990s. In this seemingly benign case, the ONNY did not ask for jurisdiction over anyone, nor did they try to tax anyone. They merely purchased back their stolen lands and claimed rights to them: the right to not pay taxes to a foreign government. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion for the Sherill case denying this claim, arguing that the Oneida could not “rekindle the embers of sovereignty that long ago grew cold.” The language she deploys reveals structures of erasure of Indigenous peoples and governance within the United States. Likening Indigenous sovereignty to an ebbing flame, Ginsburg naturalizes the imagery of a “vanishing race;” a disappearance of Oneida governance in these lands, assumed to be extinguished merely because it is unrecognizable to her. Like so many American novels, Western movies, US history textbooks, and continental philosophers, Ginsburg perpetuates this violent cliché of the “slowly fading Indian race,” within the commanding context of the US Supreme Court. She imagines that the Oneida—who were finally able to bring this case to court after over a century of denial—have emerged almost out of nowhere, and without a history of knowing who they are and continue to be.

Ginsburg’s opinion in this case also rests on the Doctrine of Discovery. That a US court can still today base decisions on a decree given by a Spanish Pope in 1493 that names non-Christians barbarians (or heathens) and thus justifiably subject to death and dispossession is almost too irrational and overtly racist to take seriously. But in the Supreme Court, such seemingly absurd propositions become an overt form of legal violence to the Indigenous peoples whose lives and livelihoods are in the jurist’s hands. Justice Ginsburg’s opinion in this case reads as follows:“…it was not until lately that the Oneidas sought to regain ancient sovereignty over land converted from wilderness to become part of cities like Sherrill” (emphasis mine). Ginsburg invokes here an anti-Indigenous hierarchy of lifeways, rendering Indian land a so-called “wilderness” that had been tamed, “civilized” by Euroamericans. Also referencing the doctrine of laches, Ginsburg argues the ONNY had “slumbered on their rights”—or waited too long to reclaim sovereignty over these lands—an insidious argument considering that state and federal governments had staunchly prevented New York tribes from bringing any land claims to court until 1974. The precedent that Sherrill set slammed the door on any unresolved Indian land claims in the United States, the majority of which take place in the Second Circuit states of New York, Connecticut, and Vermont. Just three months after Sherrill was decided, a Second Circuit Court decision in Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki denied the Cayuga Nation of New York restitution for over 65 thousand acres also deemed illegally taken by New York State. This Second Circuit Court case involving the Cayuga (Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ) peoples, whose land Cornell University’s original campus occupies, primarily applied the Sherrill ruling to deny their claims to Indigenous sovereignty and restitution. The harms of the Sherrill case, so clearly embedded in anti-Indigenous racism, have thus trampled through other Indigenous nations and, it seems, will continue to do so long after Ginsburg’s passing.

During Justice Ginsburg’s first 15 years on the court, 38 Indian law cases were argued. The rights of Indigenous nations prevailed in only seven of those cases. Indigenous nations lost in eight of nine Indian law cases for which she wrote the court’s decision, including the Sherrill case. Some legal scholars have suggested that her overwhelmingly anti-Indigenous stance on the court was due to lack of training and familiarity with Indian Law. Indian law is a complex and discrete set of treaties, statutes, and agreements that govern the long relationships existing between the three relevant sovereigns of the United States: tribal governments, the federal government, and individual states. In the United States, few law schools offer adequate training in Indian law, if they offer any at all, evidenced also by Ginsburg’s 1993 confirmation hearing. During this hearing, one Senator from South Dakota asked about her familiarity with Indian law. She replied, “I cannot pretend to any special knowledge in this area of the law,” and stated that she had never studied it or taught it. Despite the fact that she had indeed taken part in six cases as federal appellate judge that touched on Indian law, and participated in the development of an ACLU amicus brief on a Supreme Court case directly speaking to it, she still renounced any claim to competence in Indian law. In most Indian law cases in which she decided, Ginsburg drew on her knowledge of civil rights – a framework based on upholding individual rights in law.[1] Yet the framework of individual rights that civil rights law is based on ignores the question of group rights – importantly, of the over 370 treaties that tribal and Indigenous nations have made with the US federal government. Indian law cases are no small matter. They take up 5% of the Supreme Court’s docket, and court hears one or two court cases regarding Indian Law each session. Despite the prevalence of Indian law cases, training in Indian law remains paltry.

Ignorance of the law, especially by those in power, is exceedingly devastating, and as the adage suggests, ignorance of the law excuses no one. Here at Cornell Law School this injustice is being addressed. The Cornell chapter of the Native American Law Student Association (NALSA) submits that, “while Cornell Law has not always had a strong Indian law program, it is clear that the administration is working very hard to make changes. We are continuously excited about the direction CLS [Cornell Law School] is headed.” NALSA offers the following thoughtful comment on this essay:

Experts in Federal Indian Law recognize that Justice Ginsberg was a complex individual who made decisions that were wonderful for civil rights in general, and other decisions that were harmful to Native America. While our Nations will be recovering from the harm she has done to our Indigenous Communities for a long time, we recognize the good that she has done for individual Americans.

It has been rumored that Ginsburg regretted her decision on the Sherrill case more than any other decision she made. In the last few years of her life she had learned more about Indian Law and applied her knowledge to cases such as the 2020 case McGirt v. Oklahoma, in which she stood in the 5-4 majority that confirmed that much of eastern Oklahoma is “Indian territory” of the Creek Nation. Yet for the Oneida, the Cayuga, and other Indigenous peoples against whom the Sherrill decision has been used as precedent, her regret does not return the land, nor does it repair the present and future damage.

Ginsburg’s legal career is often held as a testament to her demand for justice for women – she is an esteemed icon of feminism in the US. But her destructive legacy on issues of racial justice, prisoner’s rights, and Indigenous/tribal sovereignty often goes unappraised. Her decisions regarding Indigenous peoples in the United States in particular are conscripted into a legal system that from its start has intended to erase Indigenous self-determination, and to rid all Indigenous claims to traditional home territories in the US. Time and again, so-called liberal and conservative Justices have acted to extinguish Indigenous rights and status, and the legal record is troublingly bipartisan. To the great detriment of so many Indigenous peoples, Ginsburg never troubled herself to learn about Indian law and rights until the end of her career. In August 2019, Princeton Professor of African American Studies, Eddie Glaude stated, “there are communities that have had to bear the brunt of…white Americans confronting the danger of their innocence. And it happens in every generation.” This “innocence,” Glaude says, is sometimes thinly veiled by a willful ignorance. Native experiences and Native American politics falls squarely within the blind spot of a liberal/conservative binary. In a time of stark, rising authoritarianism and white ethno-nationalism in the United States, it is more difficult than ever to sit with nuance and un-block our ears to histories, lives, and political realities that are less amplified and thus less familiar to many readers.

With her reported regret about the Sherill case in mind, would that today we could ask Ruth Bader Ginsburg her opinion about her name on this building in Haudenosaunee lands. She worked indefatigably to reform some of the harms woven through the fabric of US governance from its founding. Yet her attempts at reform have not, and many argue cannot, reach Native American people and tribal and Indigenous governments. As worthy as such advocates are of celebration, this moment requires that a campus community take stock of how our institutions and honorings are complicit in continued injustice and oppression. Racism, seen here as anti-Indigeneity, is a historical and empirical reality in US universities by way of exclusions and adverse inclusions, in many campus traditions, and certainly in course content and omissions. Again this year, departments and students at Cornell have rallied their collective voices to call out this racism and demand change on reconfigured terms. The Cornell University and Indigenous Possession Blog highlights a pathway for Cornell University to begin repairing its relations with Indigenous peoples upon whose lands and lives the institution is established. At the very least, it has been assured that the Ginsburg dorm will not be placed adjacent to Akwe:kon, which would be a serious misstep off this path. Indigenous students at Cornell, who already confront daily on-campus Indigenous erasure, do not deserve to have another reminder of entrenched ignorance of their peoples’ lives and histories tower over their community space. Currently, there is discussion with Cornell University’s Vice President for Student and Campus Life, Ryan Lombardi, and with the traditional leaders of the Cayuga peoples upon whose lands Cornell occupies, about how their people also may be honored and recognized with an NCRE dorm name. I am hopeful that these discussions continue, and materialize.

Ginsburg’s memorialization may be a beacon for many young undergraduates at Cornell who may be encouraged, like Ginsburg, to work for expansive visions of justice. That tradition can take these students beyond what Justice Ginsburg was able to accomplish during her remarkable life. To make this possible, her memorialization ought not to begin with an affront to the many Indigenous peoples who, as she perhaps realized at the end of her career, she had not done justice.

[1] Supreme Court Justices unfamiliar with Indian law may tend to “seek parallels with areas of law and modes of analysis with which they are most familiar” (Goldberg 2009, 1004)

_____

References:

Borgman, Amy. “Stamping out the embers of tribal sovereignty: City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation and Its Aftermath.” Great Plains Nat. Resources J. 10 (2006): 59.

Brasher, Jordan P., Derek H. Alderman, and Joshua FJ Inwood. “Applying critical race and memory studies to university place naming controversies: Toward a responsible landscape policy.” Papers in Applied Geography 3, no. 3-4 (2017): 292-307.

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg Wants Trump to Appoint a Native American Woman to the Supreme Court.” The Buffalo Chronicle, September 19, 2020. https://buffalochronicle.com/2020/05/05/ruth-bader-ginsburg-wants-trump-to-appoint-a-native-american-woman-to-the-supreme-court/.

City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation, (03-855) 544 U.S. 197 (2005)

Cornell University. “What Is the North Campus Residential Expansion?: Cornell North Campus Residential Expansion.” What is the North Campus Residential Expansion?” 2020. https://ncre.cornell.edu/what-north-campus-residential-expansion.

Duthu, N. Bruce. American Indians and the law. Penguin, 2008.

George-Kanentiio, Douglas M. Iroquois on fire: A voice from the Mohawk nation. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006.

Germino, Katherine E. “This land is your land, this land is my land: Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki.” Vill. L. Rev. 52 (2007): 607.

Goldberg, Carole. “Finding the Way to Indian Country: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Decisions in Indian Law Cases.” Ohio St. LJ 70 (2009): 1003.

Marshall Project Staff. “RBG’s Mixed Record on Race and Criminal Justice.” Marshall Project, September 23, 2020. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/09/23/rbg-s-mixed-record-on-race-and-criminal-justice.

Matthews, Michael. “City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation: Balancing the Correction of Historical Wrongs with the Convenience of Ignoring Them.” Okla. City UL Rev. 32 (2007): 169.

Rifkin, Mark. Manifesting America: The imperial construction of US national space. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Singer, Joseph William. “Double Bind: Indian Nations v. The Supreme Court.” Harv. L. Rev. F. 119 (2005): 1.

Williams Jr, Robert A. The American Indian in western legal thought: the discourses of conquest. Oxford University Press, 1992. Pp. 313-328.

The following is taken from The Humanities Pod, funded by The Society for the Humanities at Cornell originally posted to their website on December 14, 2020. Informal conversations with Society Fellows, Cornell Faculty, community collaborators, and special guests shine a light on some of the new work, the current conversations, and the latest ideas of humanists at and around Cornell.

This podcast addresses the relationship between Cornell University’s founding in 1862 under the Morrill Act and the United States’ prior dispossession of Indigenous nations’ homelands that provided the “public lands” utilized to fund land-grant colleges and universities.

Speakers

Jon Parmenter, associate professor of history at Cornell University

Paul Fleming, Taylor Family Director of the Society for the Humanities

Transcript

Cornell University’s administration revised its statement about the University’s land-grant mission by adding a new paragraph that acknowledges Cornell’s relationship to Indigenous dispossession both locally and continentally. This revision was based on the March 2020 High Country News article and the work of AIISP’s Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project. The new paragraph was written in conjunction with AIISP project members.

The new text reads:

As a land-grant institution, we acknowledge that the commendable ideals associated with the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 were accompanied by a painful history of prior dispossession of Indigenous nations’ lands by the federal government. As the largest recipient of appropriated Indigenous land from the Morrill Act and the institution that accrued the greatest financial benefit from that land, we also acknowledge Cornell University’s distinct place in this history. In addition, Cornell’s Ithaca campus sits within the indigenous homelands of the Gayogo̱hó:nǫ’ (the Cayuga Nation), members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, an alliance of six sovereign Nations with a historic and contemporary presence in this area. This history compels our university to ensure that the values it upholds to make a positive impact on the world align with efforts to engage with and benefit members of all communities.

Panel given during The American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program’s Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebration by Cornell University’s Professor Jon Parmenter with introduction by Professor Kurt Jordan and response by Dr. Shaawano Chan Uran. Given via Zoom on October 12, 2020.

by Professor Jon Parmenter

On October 7, 2020, Ithaca’s Common Council voted to remove from DeWitt Park an historical monument erected in 1933 by the (now-defunct) local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. This marker commemorated the “First White Settlers” in Ithaca: two Revolutionary War veterans alleged to have erected cabins near what is now DeWitt Park. Beginning in 2017, the monument came under justified local criticism for its exclusion of both the Cayuga Nation, the Indigenous owners of the land, and long-time Black residents of Ithaca.

In its attempt to correct this historical injustice, however, the Common Council’s revised resolution actually made matters worse. Their resolution states: “Whereas the land here was once home to the Cayuga Indians, one of the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and one of the Cayuga’s refugee [guests], the Tutelos and Suponis [sic]. The Cayugas fought and then fled before General Sullivan’s invading American army in September of 1779. By 1789, the land was largely unoccupied and American settlers had begun to arrive, albeit before legal land claims could be made.”

Beyond a forgivable spelling error (the proper ethnonym is “Saponis”), the resolution constitutes a more explicit erasure of Cayuga ownership and occupancy than the comparative silence of the 1933 DAR marker. It is true that after making a stand at the Battle of Newtown (near present-day Elmira) on August 29, 1779, Cayugas and other Haudenosaunee opted to take flight beyond the reach of the invading American army. This was a strategic withdrawal that saved lives at the price of temporarily sacrificing their settlements and much of their property.

But according to the Common Council’s resolution, the Cayugas abandoned the area permanently as a result of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign. That is not true – Cayugas and other Haudenosaunee returned to their ancestral homelands in the Finger Lakes region shortly after the 1779 American invasion. Had Cayuga territory been “largely unoccupied” after the Revolutionary War, the sustained, often extralegal efforts of both the national government and New York State to dispossess the Cayugas of their land base during the last two decades of the eighteenth century would have been unnecessary.

By erroneously reducing the Cayugas to victims who abandoned their ancestral homelands, the Common Council’s resolution perpetuates a misleading impression of Indigenous erasure. Replacing an outdated monument to white settlement with an inaccurate resolution that posits a terminal narrative of the Cayuga Nation’s history does yet more violence to our ability to understand and learn from the past. As the lone Haudenosaunee nation to be completely dispossessed of their land base in New York State after the Revolutionary War, the Cayugas deserve a more thoughtful representation of their history in the City of Ithaca than that offered by the Common Council. Ideally, the Common Council would consider consulting with living members of the Cayuga Nation residing locally, who can best relate the true consequences of their dispossession for the rest of us.