I want to be an aquatic veterinarian when I grow up. And no, that doesn’t mean that I just want to work with fishes. Well, at least not entirely. Aquatic veterinary medicine is not so much a field within veterinary medicine, but a completely parallel entity. In other words, there is an aquatic veterinary job for every terrestrial veterinary job. And that means that there is more to aquatic animal medicine than “just fishes.” For example, production animal vets are akin to aquaculture vets, whereas zoo/wildlife vets are typically mirrored by aquarium veterinarians. And there are plenty of other examples, too! Isn’t that super cool?!

You may be wondering how the heck you’ve never heard of any of this. Truth be told, the lack of exposure to aquatic animal health is a real problem within veterinary curricula nationwide. Granted, it would be very hard to cram even more information into an already packed curriculum. Hope is not lost, however! There are various extracurricular courses that you can take advantage of if you feel like aquatic animal medicine is for you. MARVET, SeaVet, and AQUAVET are just some of these amazing opportunities. All three are very different in terms of length, cost, and location, but they will undoubtedly expose you to the amazing world of aquatics. I know that AQUAVET did so for me.

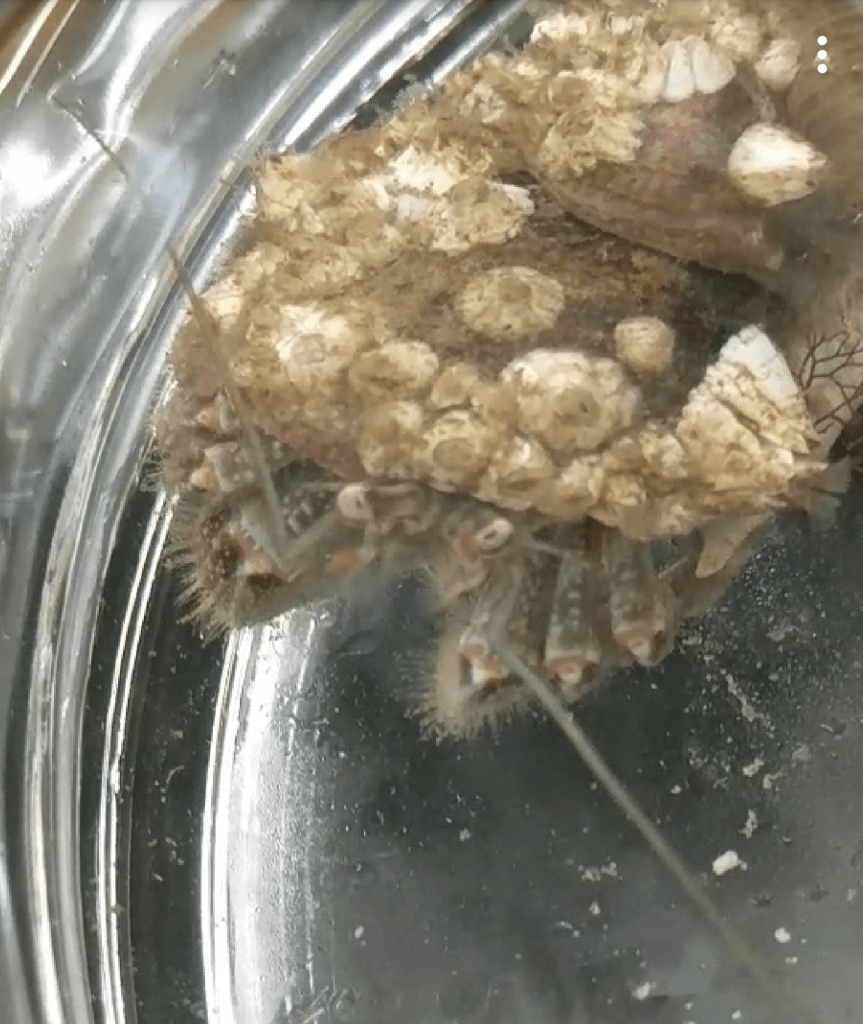

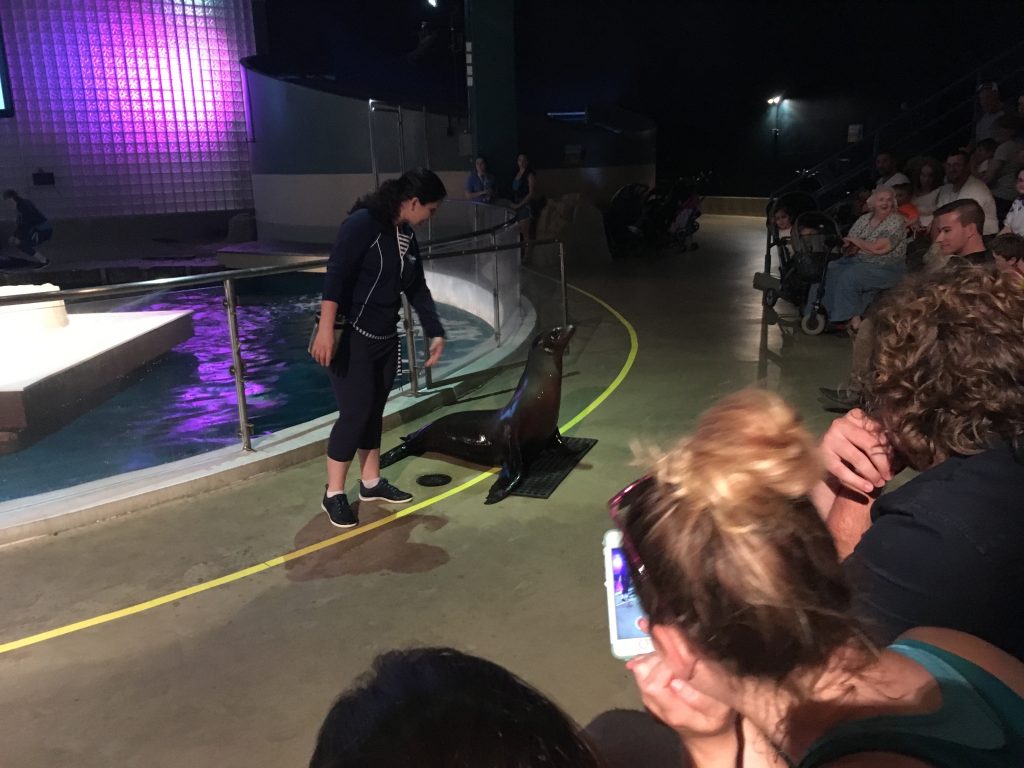

AQUAVET is a summer program that is open to veterinary students (and veterinarians) from all over the world. It consists of three courses, AQUAVET I – III, each of which is focused on a particular aspect of aquatic veterinary medicine. AQUAVET III is dedicated to clinical aspects of marine mammals, while AQUAVET II is focused on the histology and histopathology of various aquatic species. The course I was fortunate to take this past summer, AQUAVET I, is a one-month crash course on all things aquatic. It provides information on the anatomy, pathology, husbandry, and clinical aspects of a plethora of aquatic animals. From invertebrates like jellyfish and corals to vertebrates like sea turtles and marine mammals, AQUAVET I does it all! In addition to learning about these animals, I also learned important diagnostic techniques, such as fin clips, venipuncture, necropsies, and gill endoscopies. To finish it all off, I got to perform supervised surgery on a fish!

As you might imagine, there is absolutely no way that all of this can occur in a one-month time frame and not be a tremendous amount of work. Believe me when I say it is! With ten-hour workdays, five days a week (and some work on Saturdays, too), it’s a LOT of work. Fortunately, AQUAVET I isn’t all work and no fun. In fact, it feels just like summer camp for fish nerds! I got to meet amazing people from veterinary schools all over

the United States and beyond. When we weren’t studying, my AQUAVET cohort and I were playing volleyball on the sand courts, enjoying the breeze of the Rhode Island shores, or enjoying one of the many social activities that were part of AQUAVET. It was truly amazing to make connections with students who get as excited as I do when someone so much as mentions something remotely aquatic-related. AQUAVET truly made me feel like I finally found my people.

In addition to networking with students, I got the chance to meet many incredible lecturers. In fact, it’s common for there to be more lecturers than students during AQUAVET I. I received lectures from government officials, aquarium and aquaculture veterinarians, and veterinarians who have created their own jobs. The best thing about having so many lecturers come in, coupled with the fact that this field is so small, is that they all want to see you succeed. I even got a letter of recommendation from one of the professors at AQUAVET that allowed me to win a scholarship!

All in all, AQUAVET I was an amazing experience that I will cherish for years to come. It provides the opportunity to obtain aquatic animal resources and develop clinical skills related to all types of animals while building relationships with like-minded people. Without a doubt, AQUAVET has made me a more resilient veterinary student, one who is better prepared for a future as an aquatic veterinarian.

Hery Ríos-Guzmán, Class of 2024, obtained his Animal Science/Pre-Vet degree from the University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez. The island environment in which he grew up influenced his professional interests and put him on the path to aquatic veterinary medicine. He has special interests in conservation medicine and hopes to use his knowledge to improve coral reef health around the world.

Hery Ríos-Guzmán, Class of 2024, obtained his Animal Science/Pre-Vet degree from the University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez. The island environment in which he grew up influenced his professional interests and put him on the path to aquatic veterinary medicine. He has special interests in conservation medicine and hopes to use his knowledge to improve coral reef health around the world.