The Cheetah Chronicles: The Next Generation

“Teacher! Teacher!” a bundle of children would exclaim as I pedaled along the fence of the schoolyard and parked my bicycle at the front gate. These high-pitched utterances would engender a variety of sentiments on my part: melting my heart to be greeted so warmly every morning, crawling over to read a picture book with them in a pillow fort, clapping with joy at their mastery of multiplication tables, or closing my eyes in dread over the spilled juice on the classroom carpet.

“Teacher! Teacher!” a bundle of children would exclaim as I pedaled along the fence of the schoolyard and parked my bicycle at the front gate. These high-pitched utterances would engender a variety of sentiments on my part: melting my heart to be greeted so warmly every morning, crawling over to read a picture book with them in a pillow fort, clapping with joy at their mastery of multiplication tables, or closing my eyes in dread over the spilled juice on the classroom carpet.

While the primary purpose of my summer placement in Namibia was to conduct intensive research on cheetah nutrition to enhance my clinical understanding of wildlife species, it was a tremendous honor to collaborate with the AfriCat Foundation to rewardingly extend that knowledge through educational outreach. AfriCat’s teaching philosophy is based upon the following quote from Baba Dioum: “In the end, we will only conserve what we love, we will only love what we understand, and we will only understand what we are taught.” The program itself aims to increase the students’ awareness of environmental issues, develop a sense of agency regarding their roles and the sustainable living practices they can engage in, and empower them to harness their strengths and passions to become ambassadors for wildlife.

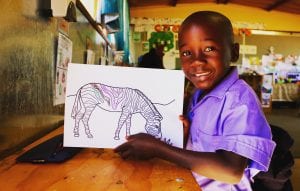

Naturally, lessons were catered to the age group of the students. With kindergarteners, we created an arts & crafts activity to illustrate diversity in nature. Using a zebra as our teaching model and emphasizing the fact that no two individuals share the same stripes, we highlighted the beauty of difference and the importance of embracing and preserving that aspect in both the animal and human kingdoms. With middle schoolers, we would take the students out on nature walks and teach them about the bushman way of life. Bushmen are members of the indigenous hunter-gatherer groups that were regarded as the first inhabitants of various Southern African countries, including Namibia. I was amazed when learning about their sheer survival ingenuity, their profound respect for animals, and the deep spirituality that connected them with nature. Whether it was hollowing out an ostrich egg and repurposing it as a water flask, fashioning the fibers of the Sansevieria plant into a rope with exceptional tensile strength, or igniting a fire purely from dry grass and friction, the Bushman culture and its traditions are actively preserved by the Namibian people. Despite increasing modernization of society, the Bushman values, rich history, and practices continue to be shared with others.

With high school and university students, we would integrate more scientific concepts into the lesson plans and explain the evolutionary adaptations of animals we would spot on a safari drive. We often had comparative discussions between the big cat species and how their anatomical differences contributed to their distinct survival strategies. For example, the characteristic black tear tracks that run down every cheetah’s face is present in order to reduce the amount of light that gets reflected into their eyes. This is to facilitate their hunting endeavors, since cheetahs search for prey during the day. On the other hand, leopards have a noticeably bulkier skull due to the attachments of massive muscles of mastication. While cheetahs are built for speed, leopards rely on stealth and incredible bite force to strike their prey.

Though days were long and filled with instruction, there were definitely more laid-back, reflective moments as well. We would watch the brilliant sunset over a placid dam, roast marshmallows over a crackling campfire, and lie underneath the African night sky to identify constellations as our bodies rested gently in the sand. On some evenings, we would convene for dinner and do a traditional “braai,” a social barbeque feast where everyone gathered around a firepit to grill sausage and game meat as the Milky Way glowed above.

The educational outreach aspect was an invaluable part of my experience in Africa, as I truly enjoyed immersing in the local Namibian culture and building relationships with children of all ages, many of whom were inspired to pursue careers in conservation. Through such education and awareness in the Namibian youth, we ultimately hope to build a future generation that can one day competently manage the carnivore populations in Namibia, devise practical solutions to human-wildlife conflict, and balance the needs of endangered species with the economic livelihood of farming communities. Although tourism generates an appreciable amount of revenue to fund conservation projects, big cat populations are still threatened by shootings due to farmland encroachment, a response that mainly stems from a lack of education about how both parties can coexist peacefully. By inspiring young students, several of whose families actually own farms, to see the value of wildlife and ignite their passions for conservation, we are addressing the imperative that saving these carnivore species undoubtedly requires investing in the youth of Africa.

The educational outreach aspect was an invaluable part of my experience in Africa, as I truly enjoyed immersing in the local Namibian culture and building relationships with children of all ages, many of whom were inspired to pursue careers in conservation. Through such education and awareness in the Namibian youth, we ultimately hope to build a future generation that can one day competently manage the carnivore populations in Namibia, devise practical solutions to human-wildlife conflict, and balance the needs of endangered species with the economic livelihood of farming communities. Although tourism generates an appreciable amount of revenue to fund conservation projects, big cat populations are still threatened by shootings due to farmland encroachment, a response that mainly stems from a lack of education about how both parties can coexist peacefully. By inspiring young students, several of whose families actually own farms, to see the value of wildlife and ignite their passions for conservation, we are addressing the imperative that saving these carnivore species undoubtedly requires investing in the youth of Africa.

This post is written by Elvina Yau and was originally published on her WordPress blog, Elvina the Explorer, on September 3, 2018.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Elvina Yau, class of 2020, is a veterinary student from Long Island, New York. She graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2016 with a degree in Behavioral Neuroscience and double minor in Creative Writing & Biology. Elvina aspires to split her time between practicing Companion Animal Medicine in the U.S. and contributing to conservation efforts abroad both as a clinician and freelance photojournalist.

Elvina Yau, class of 2020, is a veterinary student from Long Island, New York. She graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2016 with a degree in Behavioral Neuroscience and double minor in Creative Writing & Biology. Elvina aspires to split her time between practicing Companion Animal Medicine in the U.S. and contributing to conservation efforts abroad both as a clinician and freelance photojournalist.