First, let’s clear the air. Err, water. Yes, you can do surgery on a fish. No, fish surgery doesn’t happen underwater.

I’m Jason Sifkarovski, a second year vet student interested in zoo and conservation medicine. Naturally, these encompass aquatic medicine, but it can be tough to find such opportunities within a traditional curriculum. This past summer, I joined fellow Cornellians, veterinary students, and veterinarians from around the world in AQUAVET®, a month-long course in aquatic animal medicine.

AQUAVET® was first taught in Woods Hole, MA over 40 years ago as a joint venture between Cornell and the University of Pennsylvania. Today, the course’s faculty boasts an impressive list of dozens of alumni and other professionals who all migrate to its current home at Roger Williams University in Bristol, RI. I expected my fair share of fish facts, but I was blown away by the breadth of the curriculum. Invertebrates, birds, fish, reptiles, and marine mammals were all covered; we dove into natural history, anatomy, and physiology before flowing into species-specific disease, diagnostics, and treatment.

Our first lab had us collecting invertebrates in the intertidal zone for viewing under dissecting microscopes. A super up-close sea star is a sight to see! Oysters, clams, and crabs kicked off the first of our dissections, followed by fish. Starting the course off with invertebrates and shellfish made me quickly realize aquatic medicine extends far beyond aquariums and conservation. Invertebrates in veterinary medicine may sound fishy, but become much more relevant when considering the billions of dollars wrapped up in shrimp farming alone. Aquaculture’s share in global food production is rapidly rising, and veterinarians will become increasingly important to ensure food safety and sustainability, just as they are for more traditional food production.

For each species group we studied, lectures were followed by diverse selections of specimens for necropsy and histopathology. Lectures and labs were led by veterinarians in government, aquariums, research and industry, and even private practice. Each tied their experiences into the topics they discussed, contextualizing the relevance of each species and the current state of medicine. For example, we realized there were more species of fish in our lab than there are legal antibiotics for fish in the United States. That’s a sobering thought for a medical professional, but it did hammer home the idea that much work needs to be done in this relatively young field. By the end of the course, we had necropsied sharks, skates, turtles, crocodiles, ducks, gulls, and more. That’s a lot to take in for even the most fervent zoologist, but every day felt fresh and reinvigorating.

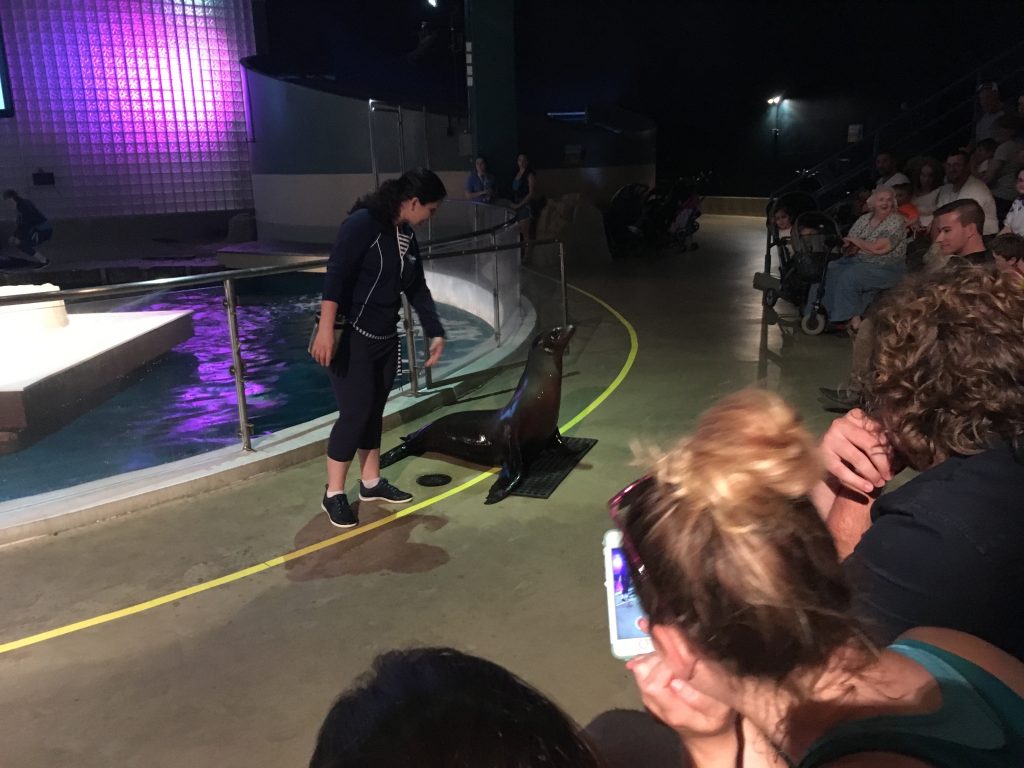

Despite all the time spent in the classroom, field trips got us outside of our bowls as well. We explored different types of aquaculture production systems with tours of fish hatcheries, and traveled to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to learn about aquatics research, and to conduct necropsies of dolphins and seals – a messy endeavor, but certainly the one I had anticipated the most. My favorite trips, however, were the aquarium visits. We performed penguin physical exams at the Long Island Aquarium, a private institution home to one of the world’s biggest reef tanks. We toured the New England Aquarium, home of the aptly-named Giant Ocean Tank and several floors of exhibits. Veterinarians at Mystic aquarium brought us along for beluga whale feedings (they’re trained to take a gastric tube for stomach content sampling!) and their reality TV-themed sea lion show, which puts a twist on education and helps visitors connect with, and retain, important messages about conservation. Given how zoos and aquariums have come under fire for captive marine mammal programs, I was particularly interested in how these institutions conveyed their conservation and educational messages to the public. These institutions serve to not only provide a safe and healthy environment for their own animals, but also conduct research and lead massive, publicized conservation efforts to provide for those in the wild. By keeping the public engaged through fun, yet educational, demonstrations like sea lion shows, they slowly but surely help the public feel involved in conservation themselves.

The highlight of the course was our surgery lab. We practiced suturing and dosing anesthesia in the days leading up to the main event: splenectomies and ovariectomies on trout. Since fish use their gills for gas exchange, powdered anesthesia is typically administered to water which may then be washed over the gills and recirculated using pumps; this means the entire fish can be held out of water for the duration of surgery. We worked in teams to calculate doses, administer anesthesia and analgesia, excise organs, and suture the incision closed. I quickly learned that fish scales provide a whole new challenge for blood draws, injections, and suturing.

When I arrived at RWU, I anticipated a course focused mostly on captive animal medicine and husbandry with some emphasis on conservation. Four weeks later, however, we had also covered aquaculture, public health, toxicology, private fish practice and trade, and countless other topics. Of course, each of these topics ties in to conservation, and I never anticipated how many extra tools I would come away with. In all its breadth, aquatic medicine suddenly felt so much more expansive, yet being taught by so many connected people made it feel accessible and intimate. I befriended terrific students who made me genuinely excited to start each day, and I can’t wait to see how many of these new friends will be teaching the course down the road. AQUAVET® provided even more than I wanted, both personally and professionally, and it can surely do the same for anyone else willing to get their feet wet.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jason is a second-year veterinary student at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. He previously graduated with a Master’s Degree in Microbiology & Immunology from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. Jason is pursuing a career in clinical zoo and conservation medicine while also maintaining interest in government and policy.

Jason is a second-year veterinary student at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. He previously graduated with a Master’s Degree in Microbiology & Immunology from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. Jason is pursuing a career in clinical zoo and conservation medicine while also maintaining interest in government and policy.