For decades, the United States’ rural towns and counties have endured the brunt of the opioid epidemic that has claimed more than 400,000 lives and left millions of people addicted.

A small West Virginia community — considered ground zero of this national catastrophe — is set to begin the first federal trial on Monday over one of the worst public health crises in the nation’s history. Cabell County and its seat, Huntington, will test a legal claim made by thousands of cities, counties, Native American tribes and other plaintiffs that drug companies ignored red flags and flooded their communities with addictive pain pills, causing a “public nuisance” and fueling an epidemic of substance abuse, overdoses and deaths.

Both of these cases highlight the complexity of accountability networks–the complex systems in which a wide array of parties hold others accountable, and are in turn held accountable. I offer these two cases studies to highlight the underappreciated role executives, managers and lower-level employees play in governance.

Let’s start with an assumption that people have a moral obligation not to drink too much alcohol at too young an age, and not to take opioids without a legitimate medical reason. You might disagree, but that’s a debate for another time–as always in moral accounting, we look to what society thinks are moral obligations, not what we personally do.

Our society sure seems to think so, because they’ve made it a criminal office to drink alcohol at 20, or to take opioids without medical authorization. But governments know that to limit such behavior, they can’t punish only these unauthorized consumers. So they also make it a criminal offense to knowingly help others do so–you face criminal liability if you serve underage drinkers, or sell someone opioids without authorization. That’s the first step down the cascade of governance.

But the cascade continues. I’ll leave the opioid governance cascade for another time (hopefully some of my students will tackle it!), and focus on hazing from here on out. Bowling Green State University and the national and local fraternity organizations will also face civil lawsuits for their roles in allowing a hazing death. But remember that moral obligations include those that no one has the will or power to enforce. So what about the parents, alumni, friends, and all those who knew about the hazing?

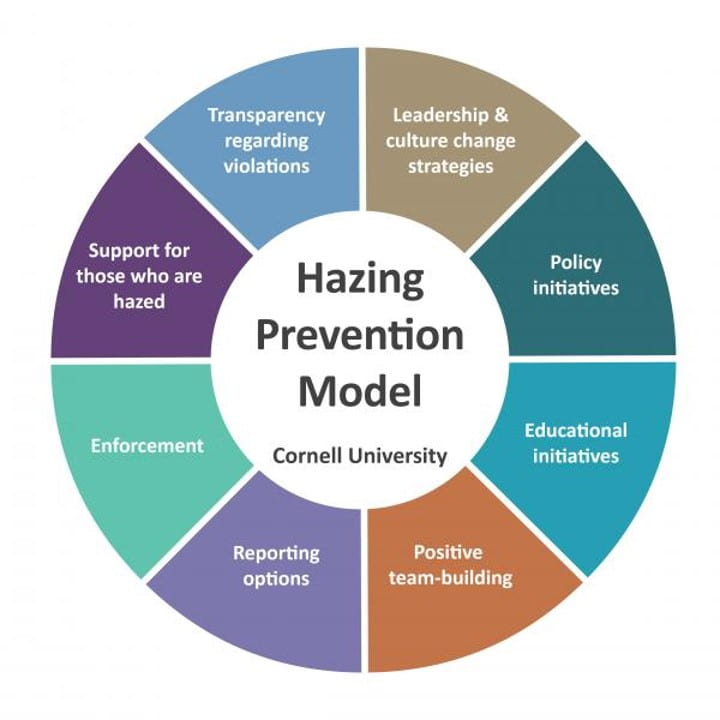

Cornell has taken hazing very seriously. Their model for preventing hazing is in the image at the top of this post. That model spells out clear policies for how various behaviors involving hazing and alcohol are punished (severely!). But the model also relies heavily on everyone, at every level, living up to their moral obligations. They emphasize that 90% of Cornell students think “it’s never okay to humiliate or intimidate new members” of student organizations. That’s up from 83% in 2014, in large part because Cornell has been highlighting how common this norm is–a very gentle form of governance that is also often effective, because (as Cornell says at the link):

Research shows college students tend to overestimate the extent to which other students are engaging in risky and potentially harmful behavior. Students also tend to exaggerate the extent to which their peers “support” or find such behavior socially acceptable. Such misperceptions influence an individual’s behavior.

Messages that include actual data to correct misperceptions and bolster positive norms are often referred to as “social norms messages.”

They also make it really easy to report violations.

So governance has cascaded from the government holding underage drinkers accountable, to the government and private plaintiffs holding facilitators accountable, to those organizations holding their community accountable, and also finding ways to get members of the community to hold one another accountable.

And this is the way it always works–when it works, that is! Governance is all around us, in the form of rich accountability networks that give everyone a role to play. That’s one of the reasons moral accounting is so expansive. It doesn’t really matter whether we are talking about “government” or “business” or “family”. We all have power to govern those around us, and we have a moral obligation to do so well. And of course, the central principle of Bookkeeping is of particular importance to executives–with greater power comes greater responsibility.