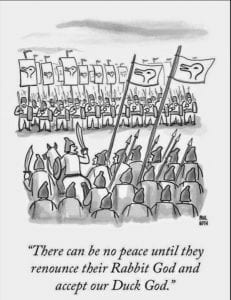

It’s become pretty standard for blogs to start every post with a picture at the top. I’ve decided to do that only rarely on this site (this post being my first exception). The reason is quite simple–good images are typically too powerful and unruly for productive discussions of moral accounting.

Last week HBS Professor Mihir Desai led a workshop on his challenges teaching a case he has written, The Tulsa Massacre and the Call for Reparations. It starts like this:

In January 2021, Oklahoma State Representative Regina Goodwin, Chair of the Oklahoma Legislative Black Caucus, considered next steps in her fight for reparations for the Tulsa Massacre. From May 31 to June 1, 1921, the predominantly Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma experienced a level of violence that “stands without parallel in America.” Perpetrators of the violence caused the death of an estimated 300 people and the destruction of Greenwood, a prosperous business district also known as Black Wall Street.

Debates about reparations offer a good opportunity to apply some moral accounting. But it’s also a very hard case to teach, and that’s what the workshop was about. We didn’t spend any time debating reparations. Instead, we debated how to teach the class.

The case is filled with images and videos, but after a trial run of teaching the case to a volunteer group of business and law students, Mihir removed one image: that of a lynching. At best, the students argued, the image was unnecessary. At worst–well, I’ll go back to the two words above–images are too powerful and unruly.

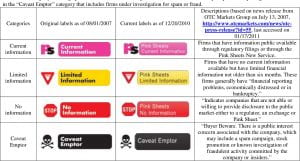

Just about any image is powerful. A huge portion of our brain is devoted to processing vision, much more than is devoted to our other senses, or to language. Pinksheets.com, an exchange for trading stocks small enough to avoid most SEC oversight, showed the power of images when they slapped yield signs, stop signs and skull-and-crossbones for firms with limited information, no information, or were suspected of scams. Investors responded pretty sharply, even though the images gave them no new information beyond what was available in writing.

A picture of a lynching is immensely more powerful than a traffic sign. And to the extent that power is emotional, it undermines one of the most useful features of moral accounting–that by focusing on accountability systems (boring!) rather than people (fascinating!) it allows more reasoned and principled evaluation of serious and controversial matters.

But worse than that, the picture Mihir used was unruly. Like the flag of the duckrabbit in the cartoon that tops this post, different people saw very different things in the same image. Some of this is context and history–especially for famous pictures, different people associate them with different contexts depending on where, when, how and why they saw it before.

A picture is worth 1000 words, but when it comes to serious and controversial matters, I want to be the one choosing those words, and I’m going to try to choose them as carefully as I can. But with images, I can choose only the picture. This brings in even more unruliness, because everyone can come up with their own answer to the question: why that particular picture? Am I taking sides? Do I mean to offend, or pander, or make light of a serious issues, or even issue a threat?

Like emotional power, this type of unruliness undermines a key goal of moral accounting: to avoid mind-reading. We rarely consider intent when evaluating accountability systems, so I’d rather not have everyone thinking about my intent in selecting an image.