“Are group projects designed to fail?”: Preventing the Prisoner’s Dilemma in Group Projects

link to article: https://medium.com/swlh/how-the-prisoners-dilemma-can-make-you-a-better-manager-15a17cd9546c

link to lecture slides: Optimal Foraging and game theory F21 Shortened Slides

There I was sitting in my lecture for BioEE1610 (Introductory Biology: Ecology and the Environment) learning about optimal foraging for animals when BAM! I got hit with game theory. I was confused as to why this crossover in my Networks and Ecology classes was happening, but once explained it makes a lot of sense.

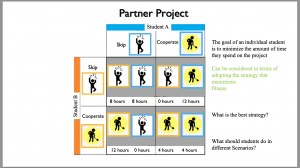

Optimal foraging involves analyzing scenarios with one animal that is making a decision to maximize their fitness, but when you add more animals (which creates a more realistic scenario for foraging) it becomes a game that can be represented through game theory. In the ecology lecture, before thinking of this in terms of animals, we were told to think of a scenario more familiar to us: group projects. The following screenshots are the lecture slides that outline the game we were playing.

Note: For the sake of not sharing my ecology course’s entire lecture content on the internet, I provided a link to a pdf that only shows the lecture slides directly related to what I am discussing in this blogpost.

By looking at the numbers in each quadrant we can tell that the game has a logical setup. It makes sense that if a student skips the meeting while the other one shows up, the student who shows up does all the work and works for 12 hours. It also makes sense that if both students cooperate, they work for less time than they would if they both decide to skip (4 hours together versus 8 hours separate).

The conclusion of this game was that no matter if your partner was someone you did not trust, just a random person, or even your best friend, it was best for you to skip the meeting because that always allowed you to spend the least amount of time working on the project. In my ecology course, when talking in regards to animals, skipping the meeting is seen as an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), which they defined to be a “behavioral strategy that is adopted by a population that cannot be invaded by another strategy”. Sound familiar? In Networks, this partner project is an example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and ESS is the same as saying the pure (non-randomized) strategy Nash equilibrium. (skip, skip) is indeed a pure strategy Nash equilibrium because for Student A, skip is a best response to Student B skipping (payoff of 8 hours of work with skip versus payoff of 12 hours of work for cooperate), and for Student B, skip is a best response to Student A skipping (payoff of 8 hours of work with skip versus payoff of 12 hours of work for cooperate).

Knowing that the Nash equilibrium is to skip in the partner project game made me wonder as to why partner projects are still so prevalent in schools and in workplaces. With this logic, are group projects designed to fail due to an individual’s self-interest?

Upon researching this, I found that I am not the only one thinking about this. In his article “How the Prisoner’s Dilemma Can Make You a Better Manager”, Jake Wilder analyzes just this. Wilder goes over the concept behind the Prisoner’s Dilemma and shares how, by understanding the outcome of the Prisoner’s Dilemma (how it’s always better for you to confess), a manager can change how they allow their employees to do group projects in a way that prevents them from acting in their immediate self interest.

Wilder makes a great point that “A critical aspect of the prisoner’s dilemma is that it’s a one-time event. Whatever you decide, there’s no chance for revenge in a subsequent round. So you’re incentivized to maximize your own personal gains.” Wilder referenced an experiment done by Reinhard Selton, winner of the 1994 Nobel Prize in Economics, where participants played a version of the prisoner’s dilemma game BUT the players did not know the planned number of repetitions, just that there was an overall limit. Selton found that as long as the end of the game was unknown, the participants put aside their immediate interest in favor of mutual benefit, “recognizing the importance of maintaining that positive relationship for the future”.

Therefore, Wilder suggested that the solution to successful group projects in the workplace was to put employees in groups that would work together on projects regularly because, by knowing that they will work on these groups again in the future, employees are deterred from prioritizing their immediate individual gains and instead cooperate to improve the performance of the group. Wilder also recommended increasing decision-making transparency because “even if people do not work with the same teams, the knowledge that their reputation will precede them is a powerful motivator”. The detriments of being known as a “slacker” in the workplace outweighs the instantaneous benefits of doing less work.

Fun Fact: My ecology professors assign us to groups at the beginning of the semester, and we work with these groups in lecture and in discussion sections throughout the semester. I’d like t0 think they were taking notes on what Wilder suggested.

I think my ecology professors did a great job of connecting concepts in networks to concepts in ecology in a way that was easy to absorb yet thought-provoking. Moreover, I think Wilder had a great analysis on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, its influence in the workplace, and how a manager can troubleshoot an employee’s natural selfish instincts to increase successful collaboration. This resource connects to topics covered in this course because they explore the idea of Game Theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma applied to group projects in both an academic and job setting.