Quadratic Vote Buying

When New York’s bike share program first launched last year, it was met with both positive and negative public responses. Supporters praised the service for its practicality in the urban setting as well as an overall greener outlook for the future, while those in opposition were concerned about the loss of parking and property value induced by the new bike stations. The results of the decision appear to clearly favor one group and put another ill at ease, which raises the question whether a more equitable strategy, which both selects a winner and offers some compensation to the loser, is possible when responding to such influential questions. This idea is explored in the article “The Good Way to Buy Votes,” by Eric Posner, which discusses notable attempts toward equitable voting mechanisms to decide these important questions and makes a recommendation of one particular strategy, the Quadratic Vote Buying scheme, developed by University of Chicago economist Glen Weyl.

One of the concerns with the use of traditional ballot referendums to decide controversial topics such as the bike sharing program is that they fail to capture the intensity of votes from a passionate minority. In the language of auctions and voting mechanisms, an indifferent majority content with the status quo may leave with a payoff of around zero while the payoff of a passionate minority plummets when a single vote of equal weight is attributed to each person.

An attempt to modulate results based on voters’ passions was made by applying the Vickrey-Clarke Groves (VCG) mechanism to the voting process. Voters submit bids for or against a program such as bike share, and the outcome with the higher total is chosen, with the winners making a partial payment to the losing side. However, one of its primary drawbacks is that the effect of collusion among individuals favoring the same outcome renders the method less robust in such a context.

The Quadratic Vote Buying method attempts to remedy some of the shortcomings of VCG through the following scheme. Each voter can purchase any number of votes whose price is determined by the square of that number of votes, and the outcome with the largest number of votes wins. Then, the payments made toward the voting process are distributed among voters in equal shares. In the context of our discussions about auctions, the following statements can be made:

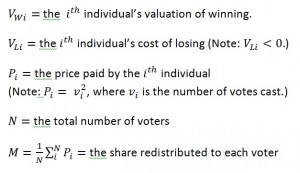

Define:

In order to quantitatively compare the benefit of winning (and similarly the cost of losing), treat the valuations using the same metric as that of the price paid to cast the desired number of votes. Then, the payoff for each winner is given by

and the payoff of each loser is

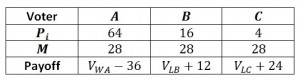

In the example pursued in the article, three individuals, here denoted A, B, and C, submit the following votes:

Voter A casts 8 votes in favor of a particular cause, voter B casts 4 votes against, and voter C casts two votes against. Since the votes in favor outnumber those against, this is the winning outcome. However, the individual payoffs are worth noting:

Let us make two simplifying assumptions to guide the interpretation of this outcome:

1. The magnitudes of valuations of winning and losing are equivalent for one voter; that is,

2. The voters act independently (i.e. there is no collusion).

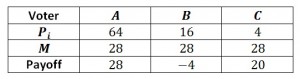

Since we are uncertain about the true value each voter has in winning or losing but can at least surmise that there is a positive correlation between this value and the number of votes cast, suppose that the true value was indeed captured fully by the price paid to cast the votes; that is,

Notice that, for winners, this ensures a positive payoff, while for losers, there is a risk of negative payoff unless M, the compensation, is sufficiently large. Now, the individual payoffs of the voters in the model can be specified.

One of the observations made in this simple model is that the vote of the minority has, in this case, triumphed, resulting in the superior payoff of voter A. However, individuals B and C receive very different compensation; in fact, voter B, who invested more in the cause, suffers a net loss, while voter C is compensated monetarily such that his payoff is nearly that of voter A. Certainly, bidding one’s true value is not a dominant strategy in this case; for the losing side, bidding less proved more beneficial. Although the passionate voter claims the overall victory in this example, the relatively indifferent member of the losing majority appears well-compensated for the loss. Perhaps, then, such a scheme is well-suited to cases where voters are divided between a passionate minority equipped to make large investments, and an indifferent majority that only makes a small contribution to the votes of one side? Some limitations of this statement are worthy of note. Adding enough members to the majority may, in fact, make the opposite outcome the winning result, even though each member makes only a small contribution. Consider adding two more voters identical to voter C. Now, the votes against total 10, exceeding that of A, but the minority has invested $64 in the cause while the indifferent majority has collectively invested only $28. This is the result of the quadratic relation between prices and votes, which generally prevents the influence of a single individual casting a great number of votes simply through wealth. In this example, however, the quadratic relation also illuminates that the number of voters is important even though a single individual can purchase any number of votes; with a steeply increasing price per individual, a large number of smaller contributions may overwhelm a small number of large contributions. Does this put favor with the indifferent majority or simply enable the voices of a more modest population to be heard and weighted in a meaningful way? It seems that a tradeoff inevitably emerges in the effort to both represent a minority of voices but also limit the influence of any one individual; the endeavors are certainly competing. However, it is worth mentioning that the Quadratic Vote Buying mechanism and other voting schemes are often effective for large populations quite different from the simple, model example. Nonetheless, in the context of our in-class discussion of auctions and the VCG algorithm and their application to an equitable assignment of goods and prices, the investigation of a different voting mechanism was an intriguing complement to the topic.

References: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/view_from_chicago/2013/06/new_york_s_bike_share_try_quadratic_vote_buying_to_figure_out_if_people.html

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2003531