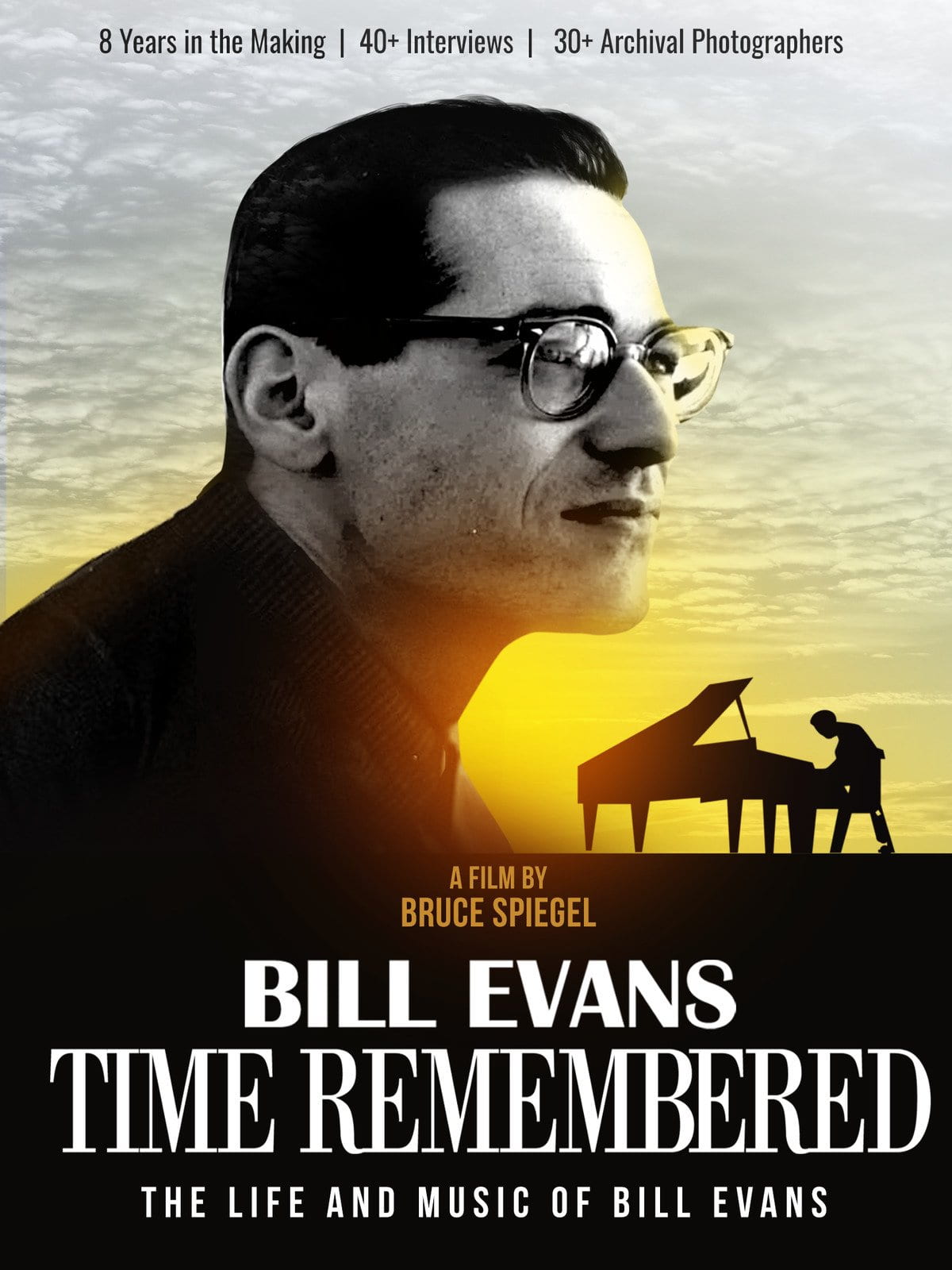

Director Bruce Spiegel mines the archives to present a tender portrait of the jazz great.

Make no mistake, this is a tragedy. Bill Evans: Time Remembered (2015) recounts the life of the inimitable jazz piano great, tracing his rise to professional acclaim and his deep personal and professional relationships to their devastating conclusion, bleeding out in a car on the way to hospital. Why this is a tragedy, Spiegel lets you decide for yourself.

Marshaling a trove of archival footage and exclusive interviews with Evans’s friends, family and colleagues, the documentary is a collective attempt at divining the man behind the music, the soft-spoken pianist from New Jersey. From the very beginning, Spiegel, speaking through the interview of bassist Chuck Israels, gives us the answer he arrived at after eight painstaking years, “Damn if I know, really. But all the information that’s really important, it’s in the music.”

Time Remembered is first and foremost a paean to Evans’s music. His all-star cast of interviewees, compromising luminaries like vocalist Tony Bennett and the recently deceased drummer Paul Motian, are most effusive when they discuss Evans’s work. Their praise may not be novel- many critics have extolled Evans’s expressive touch and command of harmony – but this profusion of jazz notables consistently lauding Evans’s deep connection to his music drives the point home. In the words of Marty Morell, Evans’s longest serving drummer, “He’s just so connected to his heart.” We associate genius with surpassing the common man, but Evans’s power lay in his unflinching portraiture of his humanity. You don’t need to understand bebop enclosure or modal jazz to be moved.

Spiegel lets the music speak for itself. He intersperses discussions of Evans’s work in the context of the 1960s jazz scene with snippets of his recordings. For a full minute, Spiegel makes you sit with “Peace Piece” (1958), a delicate meditation, cradled by the same three chords on the bass clef as the melody winds its way from serenity to bittersweet longing, before it is soothed into resolution. Friend and poet Bill Zavatsky closes the segment, declaring “Bill spoke to me in a way I hadn’t heard anyone talking.”

And Evans spoke chiefly through his music. Referring to the famous photographs of him bent in concentration over the keys, lyricist and critic Gene Lees says they were “a pretty accurate portrait of his personality”. His playing was unequivocally articulate, but he seemed to physically shrink from the world. In a clip of Evans at the piano, his lanky, spare frame is almost curled in on himself with only his arms extended, long, tapering fingers murmuring across the keys. Photographed with the famous 1961 trio, he does not wear attention with Motian’s suave polish or bassist LaFaro’s affable grin. He hangs back, nursing a nervous smile. Even further back in the archives, Evans rarely breaks with his terse professorial persona. In footage of him smoking, the gaunt planes of his face are rendered in stark monochrome, eyes shaded over by his glasses, the set of his shoulders guarded. In his childhood photos, his neutral half-smile is unreadable.

With a suite of exclusive interviews, Spiegel edges the curtain back on Evans, the man. Brother of Harry. Mentor to Scottie and Marc. Lover of Ellaine, Nennette and Laurie. Father to Evan. The warmth of his character bleeds through in his praise for LaFaro, enthusing “he was a constant inspiration to me.” You see his deep love for his family, in the uncontrollably fond smile of Debby Evans, Evans’s niece for whom he wrote Waltz for Debby, as she recalls their trips to the beach and her uncle and father, “two jazz brothers”, in animated conversation at the piano. Through Laurie Verchomin’s eyes the audience encounters Evans, the tender romantic, as she describes visiting him in New York at the start of their relationship. But we bear witness also to the corrosive self-doubt he laboured under. Bob Brookmeyer recounts how at the Cafe Bohemian with the Miles Davis Sextet, Evans was crouched in the corner, adamantly refusing to go on, insisting “I can’t play good, I can’t do this”. We see the sensitivity of his character, the weight of his grief. In the aftermath of LaFaro’s car accident, Evans, bewildered and in denial, admits “I can’t comprehend death,” with a trailing hesitance. Evans, falling silent at the piano midsong, tears streaming down his face, on the day his brother committed suicide. Talking to Zavatsky near the end of his life, Evans admits he can find no reason to stay alive.

But this is no Hollywood tell-all. Rooted in their deference for him as a mentor and bandleader, they keep a respectful distance from the details of his personal life, particularly its painful episodes. Discussing Evans’s addiction, they hint at his “inner demons” without pinpointing them. But there are some telling flashes of emotion. The disdain is evident in Orrin Keepnews’s, Evans’s record producer, voice as he narrates “Almost imperceptibly, he became a junkie.” Lees unblinking intones,“I think he hurt a hell of a lot of people.”

More than reconstructing his life, Spiegel brings Evans back into conversation. Recordings of Evans talking or playing bookend each segment, and the effect is disconcerting. The audience rarely sees Evans speaking on tape, mostly encountering him as a disembodied voice floating over monochromatic stills, an echo of the past. In his taciturn remarks, we are scrying for hints of his inner world as he moves forward through his turbulent life, while we look back, knowing what comes next. Evans’s work is an uncannily prescient soundtrack to the twists and turns of his life. The tender warmth of “Lucky To Be Me” (1959) accompanies rare childhood photos of him smiling toothily, arm in arm with his beloved brother, Harry. Its bittersweet undertones almost foretell Harry’s devastating suicide, which precedes Evans’s death by a year. Spiegel opens the discussion of Evans’s addiction with a foreboding passage from “NYC’s No Lark” (1963), as his colleagues recount what Gene Lees called “the longest suicide in history.” There in the music, Evans speaks back.

I left the documentary feeling empty, forlorn. But I couldn’t quite pinpoint what about Evans’s life was so affecting. Was it in the way he passed, the abject irony of him succumbing on the way to rehabilitation? The turmoil of his personal life? Or the cruel symmetry, between the deeply-felt humanity of his work and his self-inflicted cruelty? Perhaps it was all of these, and that we want our heroes to be happy. Even if it was just a mirage constructed by pithy one-liners, a flash of a smile in a yellowing photograph, the sigh of a melody, I saw in Evans a kind, gentle character who might have deserved that happiness.