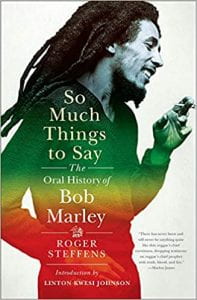

Roger Steffens Has So Much Things To Say In 2017 Book on Bob Marley

Roger Steffens’ 2017 biography, So Much Things To Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, dives into the life of Bob Marley from the perspective of those closest to him. Contrary to many other biographical works done on musicians, Steffens’ book makes Marley into a person, a friend, even. And for people like me, whose exposure to reggae is limited to the Arthur theme song and familiarity with a few Bob Marley songs through a “Reggae for Kids” CD from my youth, Steffens’ writing is understandable and intoxicating. With contextual tidbits sprinkled in between page-long anecdotes from band members and friends, So Much Things to Say pays homage to Marley through an intimate and accurate account of his life. As Marley earned his fame through his congenial and positive personality, Steffens returns to those who knew his kindness best of all. Steffens’ book, filled with the history of reggae and tales of Marley’s life, offers an honest look at what made the reggae superstar such a unique performer and so intoxicating to audiences.

In this great future, you can’t forget your past – “No Woman, No Cry”

The book starts in Jamaica during Marley’s youth. Born in Nine Mile, Jamaica to a single mother, Cedella Booker, Marley lived day by day, finding joy in the mundane. He never saw his poverty and familial situation as a setback, however, and found community among others in similar economic situations. As we enter Marley’s life in Trench Town, Kingston, we hear from Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, childhood friends of his who would become the original Wailers. In Trench Town and other slums of Kingston, music was an outlet for antsy youth and adults, providing a channel for energy that would have otherwise been spent on school or a career. “Among the only ways that law-abiding people were able to escape were through sports or music,” Steffens informs readers, “and the area was known as an incubator of great talents in both fields.”

And I hope you like jammin’ too, ain’t no rules, ain’t no vow, we can do it anyhow – “Jammin’”

Junior Braithwaite, one of Marley’s vocalists, remembers the original band, before their music career became serious, saying “the Wailers was like just a singing group, a harmonizing group. We had nothing to do with instruments.” When Bob, Bunny, Peter, Junior, and Beverly began making music together, they were just kids having fun. Their music was from the soul, the financial barriers that barred them from other activities had no influence on the songs they could create through the vessel of the voice. Led by Joe Higgs, a respected singer who was integral in the foundation of Jamaican reggae, they weren’t always trying to create something beautiful. Singing was simply something fun to fill their days. Alvin “Seeco” Patterson, a percussionist who grew up with Marley, wasn’t a part of the group but knew of Marley’s love for music, saying “it was a spiritual thing, from he was very young he was planning to sing to people.” According to Junior Braithwaite, “to us, [making music] was just fun” and in Jamaica, “singing was just something that everybody needed to do…It wasn’t like something special that no one else couldn’t have done. And while Marley enjoyed singing casually and with his friends, he wanted to do more. He knew his voice was meant to be heard around the world.

Most of them come from Trench Town, we free the people with music – “Trench Town”

The first studio album released by the band, “The Wailing Wailers,” was a hit within the Jamaican community. “Simmer Down,” the first and most notable single off the album, echoed off of radios all over Kingston. Beverly Kelso describes the track’s popularity, saying “It was like Trench Town light up when ‘Simmer Down’ come on the air…Everybody radio turn up blast high.” Perhaps “Simmer Down” was so irresistible because of its casual nature, obviously the product of a bunch of kids in Trench Town jamming with one another above unembellished instrumentals. The track is raw and understated when compared to Marley’s more well-known tracks that he produced in his later years. But then again, Marley’s career was never about singing “correctly.” Joe Higgs, Marley’s idol and mentor, noted Toots’ (of reggae legends Toots and the Maytals) reaction to Marley’s first album release, “Toots turned to his partner, listen to this, this is the group that’s going to give us a hard time, and they can’t even find their key.” Molded by the sunny beaches and carefree lifestyle of Jamaica, Marley’s music has been loved for its easy-going tone and powerful lyrics, more than the complexity and accuracy of the composition.

Don’t let them change ya! Or even rearrange ya! – “Could You Be Loved”

The middle of the book follows Bob and the Wailers as they gain fame, releasing new works and touring internationally. The band members realized the impact that they could have upon the ideologies of those who listened to their music. Marley wanted to spread positivity to his audience, so when political conflict was getting worse in Jamaica and the Wailers were asked to perform for Edward Seaga, who was running for office at the time, he was torn between remaining impartial and representing his community. George Barrett, a reggae radio DJ and cousin of the Barrett brothers who played with Marley as the Wailers, explained how Marley decided that he would perform for the candidate, “Seaga was representing Western Kingston. Bob lived in those areas. So Bob didn’t want any conflict…his music was beatin’ down this politics that was breaking up the community.” To Marley, he had a duty to spread Rastafari, which included preaching peace and unity. Promoting a political figure contradicted his beliefs and he didn’t want to be divisive. Years later, as tensions grew in Jamaica and violence became unbearable, Marley realized that he needed to represent the community that shaped him. The slums of Kingston were being destroyed and people were beaten daily; Marley, a beacon of hope with a large following, was obligated to be the voice of the disenfranchised.

Free yourselves from mental slavery – “Redemption Song”

During 1973, Bob Marley had a secret relationship with Esther Anderson, one of many affairs that the star would have during his short life. A gorgeous and outspoken Jamaican actress, Anderson helped Marley begin to think about politics and revolution, telling Steffens, “I was teaching Bob how to be a rebel, based on what I learned from living with Marlon Brando for seven years.” From their conversation on a plane from Haiti to Jamaica, Marley and Anderson wrote one of Marley’s timeless anthems, “Get Up Stand Up” which would go on to inspire communities globally to speak up about injustice and fight for their rights. During the seventies the Wailers began churning out songs with bolder and more controversial messages than their previous Rasta-filled tracks. Lee Jaffe, an American artist who lived with the Wailers in Kingston and has written extensively on their music, speaks to Steffens about helping Marley write “I Shot the Sheriff.” “[Jaffe] came up with the line, ‘All along in Trench Town, the jeeps go round and round. ‘Cause the police and military drove jeeps.” Jaffe goes on to explain why this line was so important to him, “I was thinking of…what it was like for the poor people, the sufferers.” Not only does this anecdote highlight the evolution of the Wailers’ lyrical complexity, but also the importance of collaboration in Marley’s composition process. Another politically-motivated song, “Burnin’ and Lootin’” took inspiration from a traumatic event that Joe Higgs experienced, “he had awakened to find the police surrounding and raiding his house in Trench Town. So [Esther] told Bob about it and said that we have to write about it.” The Wailers had the freedom to make comments on the political and social landscape around them, and did so through catchy tunes and funky guitar lines.

Get up, stand up, stand up for your right – “Get Up, Stand Up”

One of the biggest catalysts for Marley’s success in the United States was his rebellious spirit. His new songs filled with empowerment arrived in the seventies, during a time when young Americans were gathering in hundreds to protest injustices. Gayle McGarrity, a friend of Marley’s who taught Marley about the political institutions and inequality around the world, was originally a fan of the group, telling Steffens “because we were all so into very leftist, revolutionary stages of our lives, this group just became the articulators of our deepest, most innermost political feelings.” He gained respect from audiences who had radical ideas but needed someone to tell them, get out there and change the world! “Marley became the voice of third world pain and resistance…” states Jon Pareles, chief music critic for the New York Times,“outsiders everywhere heard Marley as their own champion.” Marley was never performing for the fame nor the money. He was a kind of prophet for the communities of oppressed individuals all over the world, who could listen to his music and hear a man singing for them.

Until the philosophy which hold one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned, everywhere is war – “War”

Using their role as international stars, the Wailers produced music that encouraged empathy and equality, even addressing specific conflicts in different parts of the world. According to Gilly Gilbert, Bob’s personal chef and good friend, “Don’t business whether your color white, or your color black or pink or blue. No racism in Bob at all.” So when the Rhodesia Bush War was coming to an end in Zimbabwe, Marley and the Wailers packed up their things and flew to Africa, determined to provide a voice for the black community of Zimbabwe, who had risen up and won. Steffens describes the role of Marley’s music in Zimbabwe during the conflict, saying “Marley’s song ‘Zimbabwe,’ though banned, had become a rallying cry among the freedom fighters.” Marley’s performance in the newly independent Zimbabwe became a prime example of his role as a figure of hope. When looking at the stage prior to his performance, “I saw him cry,” Dera Tompkins, the Wailers’ unofficial tour guide for their Zimbabwe trip, recounts, “and it was because he loved revolution and he loved revolutionaries. Because he was really like them.” Though he had the privilege of being a light-skinned man in Jamaica, Marley grew up in poverty and saw people close to him suffer as the result of their social status. His Zimbabwe performance was a powerful experience, a reward to those who did as he encouraged and rose up against their oppression.

Forget your troubles and dance, forget your sorrows and dance – “Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)”

In the final pages of the book, Marley’s friends and managers share their experiences with the cancer-stricken musician. It was the eighties and we learn about the composition of Marley’s final album, Uprising, a solemn compilation of tracks that encapsulated the hopelessness that the Wailers were experiencing at that point. “It was filled with intimations of mortality,” Steffens describes the slow-moving final work, “and [in ‘Work’] he counts off his final days.” With each page, tragedy comes closer and closer, as the Wailers begin their world tour. During the New York leg of the tour, Marley’s bandmates were finally made aware of his illness when he “had an epileptic-type fit, foaming at the mouth” in Central Park. It’s heartbreaking to read the experiences of the Wailers and friends of Marley’s when they realized his condition. Dessie Smith, Marley’s personal assistant and friend, said that after Marley’s first visit to the doctor, “he was just like out of it…he was just like limp. He wasn’t saying nothing.” Though not everyone knew the details of his illness at the time, those around him saw the once happy-go-lucky Marley become depressed and empty. In Pittsburgh, the Wailers decided they would perform for the final time, though according to Junior Marvin, guitarist and singer in the group, “if [Marley] could have done a dozen more shows after that, he would have done it.” It came down to pressure from those around him for Marley to agree to make Pittsburgh his last show, revealing the enormous impact that the singer’s friendships had on his career.

One good thing about music: when it hits you feel no pain – “Trench Town Rock”

Marley’s health got worse, and with it went his happiness. Shipped off to Dr. Josef Issels, who had a renowned yet controversial cancer clinic in the German Alps, Marley was on his own in the antithesis of his hometown. Cindy Breakspeare and Rita Marley, Marley’s girlfriend and wife, “felt that Mexico would have been a better place, because we felt the climate and the culture, he just would have been more comfortable there.” Hearing those who cared for Marley the most lament about the way he was spending his final days, it is obvious that just as music brought Marley closer to people, these relationships were integral to his state of mind. Zema, an American reggae singer who visited her mother at the clinic and, in turn, met Marley during his last few days, remembers Marley expressing his love for Jamaica, “he spoke slow and pensive and described the beauty of Jamaica…he made you feel like you were right there in Jamaica even though there was three feet of snow outside.” On Marley’s birthday, the two played guitars and sang together, “Bob didn’t play very long or very loud…just jamming…I got the impression he wasn’t doing much of that anymore.” Perhaps being surrounded by those who demonstrated their love for Marley through music would have helped the ill musician heal. He told his son, Stephen Marley, “Just sing that song there, money can’t buy life.” Until the end, Marley was never overcome by his wealth and fame. He simply wanted to sing for people, sharing important messages and spreading love.

I wanna love ya, every day and every night – “Is This Love”

The last chapter of the book, “Marley’s Legacy and the Wailers’ Favorite Songs” encapsulates the impact that friends and family had on the musical talents of Marley. Since Steffens is a collector of reggae materials, he has been able to host the Wailers at his Reggae Archives. In 1987, Steffens writes, “we looked at three hours of videos that have been held back from the public.” Then, he asked each member to share their favorite tracks. Junior Marvin’s favorite was “War,” since “every time Bob sing ‘War’ is like the first time him ever sing it, and the last time.” Al Anderson, guitarist, preferred “Roots,” because he watched Bob write it, and said “I just hadn’t seen anyone work like that, and use all the elements that were in front of him, and put them into songs like that.” “Bob wrote his songs in community,” Steffens tells us, “the band would sit around on the porch or in the studio and people would throw lines at him.” From the very beginning, music was a means of connecting with others for Marley and the rest of the Jamaican community. And until his dying days, Marley’s need to bond with others was evident. Bob Marley’s music has lived on into the 21st century, not because of unmeasurable talent, but because it was always from the heart. Every song, every note, every rhythm, is the product of friendship and beckons us to connect with one another. For Marley maximized the power of music; he asked us to take a break for just a few minutes and listen to the wailing coming from Jamaica.