By: Michele Hamill and Jill Iacchei

Opening on October 17, 2014, a new exhibit in the Hirshland Exhibit Gallery, Carl A. Kroch Library, celebrates Cornell University’s Sesquicentennial.

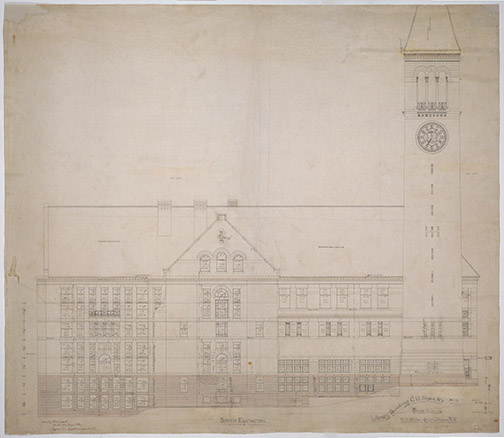

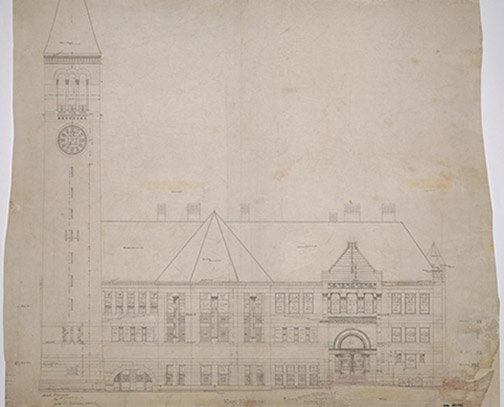

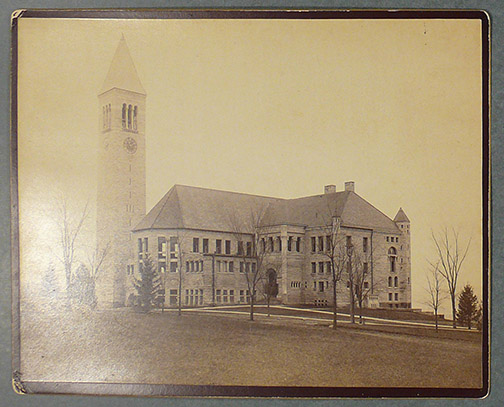

The original linen drawings for the University Library (now known as Uris Library) were treated in the Conservation Lab for the exhibit. The University Library, as well as several other campus buildings, was designed by Cornell’s first architecture student, William Henry Miller, and is known as his masterpiece.

The South Elevation of the University Library—the view when walking up Ho Plaza toward the Arts Quad.

The linen (or tracing cloth) drawings of the University Library are well over a hundred years old but remain remarkably beautiful and resilient. Tracing cloth was a strong, durable and translucent support, sturdier than tracing paper. It retained its strength and flexibility and could endure heavy handling and rolling, an important attribute for working drawings such as elevations and floor plans.

Commonly called linens, the tracing cloth was predominantly made from cotton which was free of lumps and imperfections. The plain woven cloth was heavily coated with starch, making the coated cloth more resistant to tearing than untreated cloth or paper. The coated cloth was then heavily calendared by pressing through hard rollers to compact the fabric and create a very smooth, glossy, drawing surface.

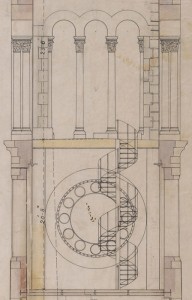

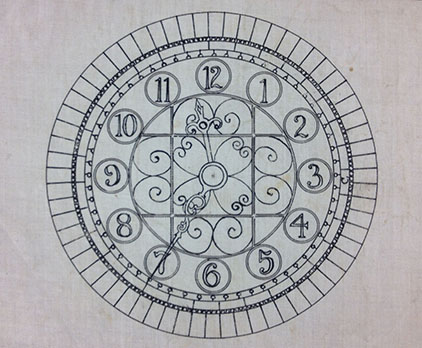

A detail of the clock face showing how the smooth surface provided an ideal coating to take ink and produce sharp, crisp lines. Notice anything different from clock drawing and the actual clock?

A detail of the clock face showing how the smooth surface provided an ideal coating to take ink and produce sharp, crisp lines. Notice anything different from clock drawing and the actual clock?

The University Library drawings have accent watercolor applied to the verso of the drawings, as seen in this detail of the spiral staircase of the clock tower, which results in subtle shading to select parts of the drawing. The color was applied to the back of the drawings to avoid disrupting the inked images which rest on the surface of the starch coating and were very sensitive to moisture.

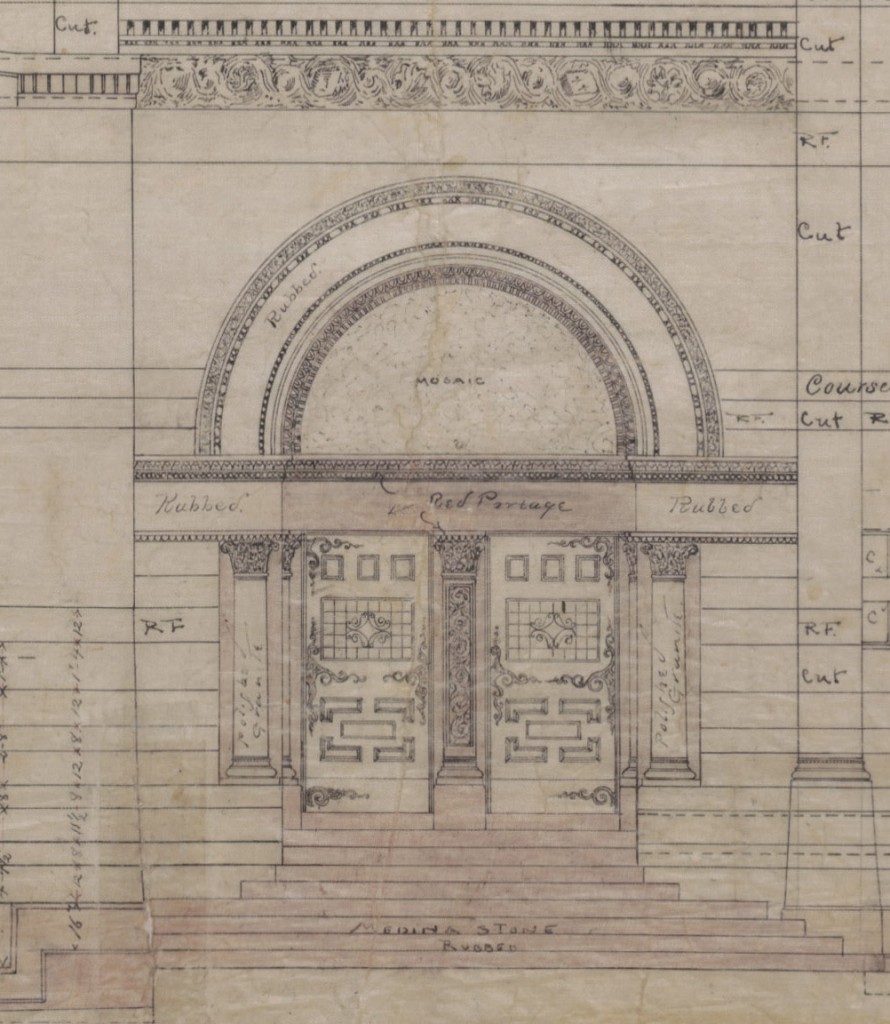

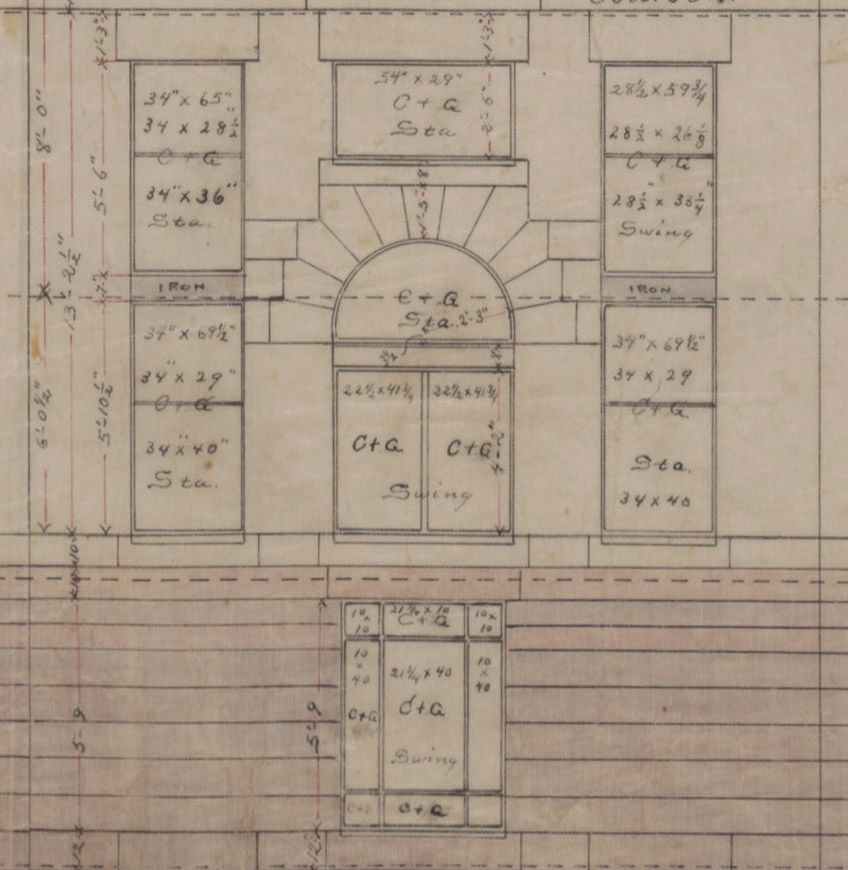

Detail, main doors, East Elevation.

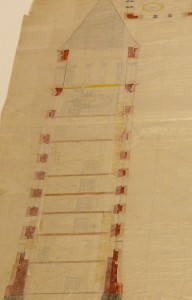

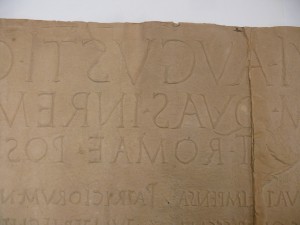

Working drawings were not elaborately colored, but were selectively tinted with flat, simple washes of color. A standard color code was used by architects to clarify structure and to indicate the construction materials —red indicates brick, ochre denotes wood, and blue indicates iron.

Drafting manuals from the late 19th century specified that red ink should routinely be used to indicate distance marks, as seen in the left of this detail of the West Elevation. Notice how the word “IRON” is written to the left and right of the window, as well as the area tinted blue. Because the tinted color did not reproduce in the blueprints made from the linen drawings, the drafter also indicated the construction materials through words or symbols.

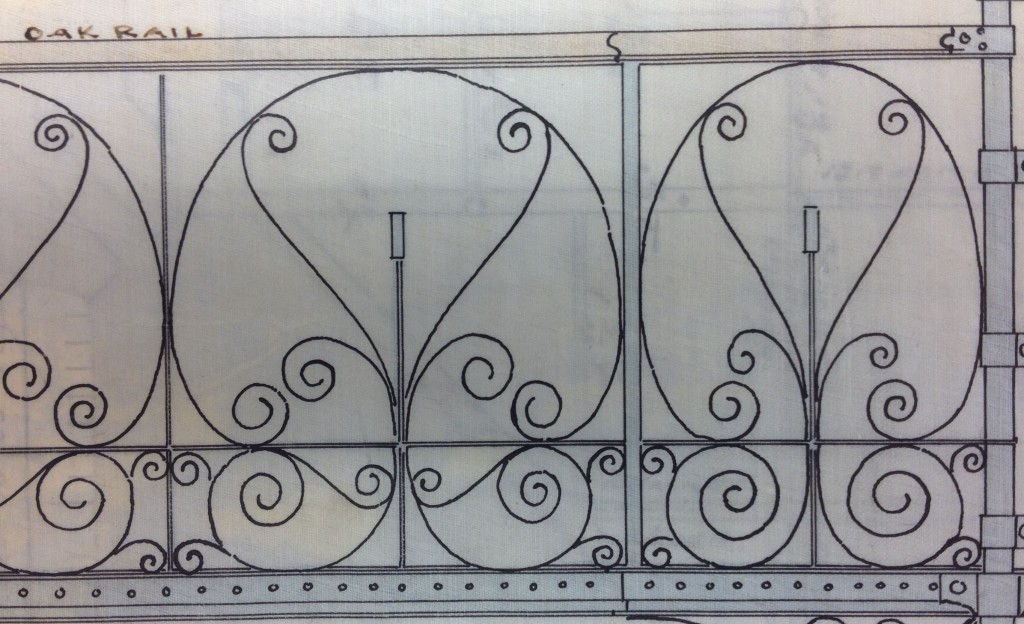

This detail shows the metal work for the A.D. White Library which is housed inside the University Library. Drawings on tracing cloth served as the master for making expendable blueprints for workmen to use on-site. Linen drawings can have an overall blue or blue-grey tint, as seen here, due to colorant added to increase their transparency to the actinic (photosensitive) light needed to produce blueprints.

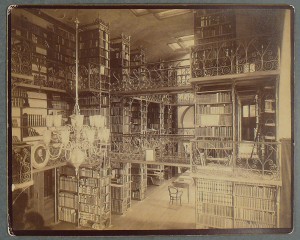

This albumen photograph, cleaned and stabilized for the exhibit, shows the interior of the A.D. White Library with the magnificent metal work conceived in the drawings.

The drawing for the East Elevation and the 1891 albumen photograph showing the north and east elevations of the completed building.

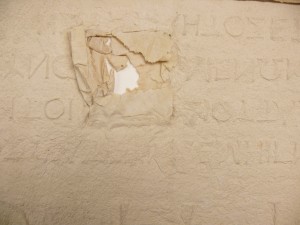

The treatment of the University Library drawings included surface cleaning, removal of old, failing repairs, stabilization, and flattening. The linen drawings responded well to treatment and will continue to serve as a historical record, as A.D. White asserted, of ‘the best academic library built’.

Thank you to Rhea Garen, Lead Photographer DCAPS, for providing the elevation images seen above.

The Sesquicentennial exhibit showcases a wealth of photographs, memorabilia, and documents depicting the inspiring history of Cornell University. For more information on the Sesquicentennial exhibit, see: http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/events/current_exhibitions.html