J.M. Iacchei

Three years ago in the Fall of 2013, one of my first assignments here at Cornell was to spend some time in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections’ (RMC) reading room with a very old and sizeable papyrus. I was asked prepare a condition report identifying the conditions and factors contributing to its current and future state. The item was a 2300 year old funerary text dating back to the Ptolemaic Period, 330-220 BC, belonging to an Egyptian Stolist priest who went by the name Usir-Wer. The papyrus measures about 8 feet in width and 1 foot in height.

Fredrika (Freddy) Loew, a former graduate student in Archaeology and current Senior Manuscript Processor in the Division of Rare and Manuscripts Collections, began working on the papyrus translation in 2013. She brought it to the attention of Michele Hamill (Paper and Photograph conservator). It was at this time that I conducted the initial condition assessment, but it wasn’t until the summer of 2015 that we revisited the papyrus in preparation for digitization and the Gods and Scholars exhibit.

In the lengthy text that follows, I will tell you about Usir-Wer, the history of his funerary text, and the conservation treatment in preparation for digitization and exhibition. I will take you through this somewhat chronologically, starting from the very beginning….

320-330 B.C Usir-Wer was a Stolist priest during Ptolemaic Egypt. This was a high ranking position in Egyptian society and carried with it the responsibility of tending to the care of the temples and statuary where it was believed that the spirit of the deceased, the ka, found a permanent resting place. By tending to the needs of the deceased and performing rituals, order was maintained and the gods were appeased. It was believed that failure in these responsibilities would lead to disorder and anger of the gods.

320-330 B.C Usir-Wer was a Stolist priest during Ptolemaic Egypt. This was a high ranking position in Egyptian society and carried with it the responsibility of tending to the care of the temples and statuary where it was believed that the spirit of the deceased, the ka, found a permanent resting place. By tending to the needs of the deceased and performing rituals, order was maintained and the gods were appeased. It was believed that failure in these responsibilities would lead to disorder and anger of the gods.

Religious ritual traditions practiced by the Ancient Egyptians have a deep history extending back well before they were documented in written form – objects found at burial sites, extant papyri, inscriptions and imagery found on tomb walls each provide insights. Among archeological findings is a body of texts known collectively as funerary texts. Under scholarly study, separate groupings have been distinguished-the Book of the Dead being only one of them, though perhaps the most secularly familiar. The others include: Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, Books of Breathing, and Books of the Netherworld. These texts contain ‘mortuary liturgies’ and ‘funerary literature’ or similarly ‘collective ritual’ and ‘personal recitations’ to be used on behalf of the deceased or by the deceased in preparation for or during his journey through the afterlife.

The origins of these spells, recitations, litanies, and hymns are unknown. Separate and distinct, the texts span across time periods, and present differences in content and emphasis but all share a common theme: the preparation of the deceased in the afterlife by offering assistance in the form of protection and provisions – and this is what we find in Usir Wer’s funerary text.

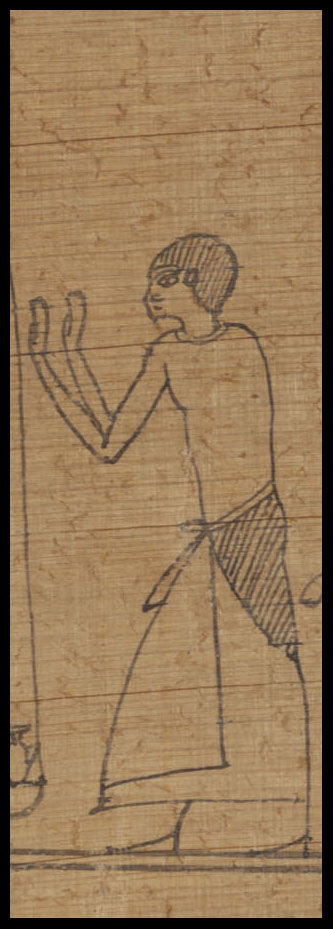

This vignette from the papyrus shows Usir-Wer in the Hall of Judgment. Above are the 42 gods to whom he must address in his negative confession–all the sins he has NOT committed. Usir-Wer is on the right facing Anubis as his heart is weighed against the Feather of Truth. Thoth is on the left ready to record the verdict of the balance. Ammit is ready to devour the heart should Thoth not proclaim it righteous.

This vignette from the papyrus shows Usir-Wer in the Hall of Judgment. Above are the 42 gods to whom he must address in his negative confession–all the sins he has NOT committed. Usir-Wer is on the right facing Anubis as his heart is weighed against the Feather of Truth. Thoth is on the left ready to record the verdict of the balance. Ammit is ready to devour the heart should Thoth not proclaim it righteous.

So how did Usir-Wer’s funerary text find its way to Ithaca? 330BC-1990’s

From the time of Usir-Wer’s burial, circa 330-320 BC, until its excavation in 1887, the papyrus remained rolled and held within his tomb; where exactly in Egypt we are not certain. It was purchased two years later in 1889 by Cornell University President A.D. White while traveling in Cairo. At the time of its purchase, the papyrus was no longer rolled but had been opened flat, mounted, and framed– which White noted, along with some other significant details, in his letters to his colleagues back in Ithaca – more about that in a moment.

About the content, he tells us that it was found in the tomb of a priest of the Ptolemaic period, is written in hieroglyphs, but mainly hieratic, and the text was “an extract from the Book of the Dead”. Over time this became “telephoned” into “It is the Book of the Dead,” likely due to its prominent vignette of the Judgment Scene, Spell 30B from the Book of the Dead. This mis-interpretation was not clarified until 2013 when Freddy began to translate the text and verified her findings with the letters. The parts of the text that are not from the Book of the Dead, are more like rituals and prayers to be said on behalf of or by the deceased to ease his passage into the underworld.

Upon arrival in Ithaca, the papyrus was hung in the Seminary room of McGraw Hall and then moved to Uris Library sometime in the 1890’s, displayed from time to time, and at one point, re-framed. Beyond this there is no record of the papyrus or how it was stored; nor was it ever given a call number. At the time of the construction of Kroch Library in the 1990’s it was moved to the vault for storage.

Before we can talk about the condition assessment or the conservation treatment, it is worth taking a brief moment to talk about Papyrus, how it was made and how this process informs our understanding of the current condition.

The papyrus is cut at its base; the outer stem is removed; the inner pith is cut into strips, and the soaked in water until pliable and translucent; the strips are placed in two layers perpendicular to each other, and then pressed. Rolls were made by overlapping the left edge one piece over the right of the next with the horizontal fibers on the inside. This construction facilitated the ease of writing on the inside of the roll from right to left. The papyrus would have then be rolled; this is how we would have expected to find Usir-Wer’s funerary text at the time of excavation.

The papyrus is cut at its base; the outer stem is removed; the inner pith is cut into strips, and the soaked in water until pliable and translucent; the strips are placed in two layers perpendicular to each other, and then pressed. Rolls were made by overlapping the left edge one piece over the right of the next with the horizontal fibers on the inside. This construction facilitated the ease of writing on the inside of the roll from right to left. The papyrus would have then be rolled; this is how we would have expected to find Usir-Wer’s funerary text at the time of excavation.

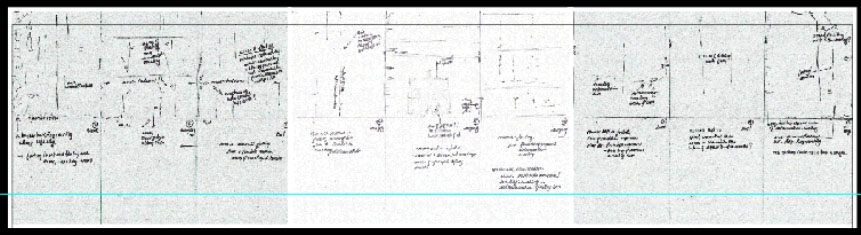

In 2013, Freddy began her research and I conducted an initial condition assessment. We hadn’t yet learned of the letters from A.D. White mentioned above and so only knew what could be seen through the glass. Un-framing the papyrus at the time of its condition assessment was not an option because it was uncertain how the papyrus would react. Once unframed, we needed to be prepared to react appropriately. Below is a sketch of the papyrus I made to accompany the condition report:

I could see that it was constructed of 9 sheets of papyrus adhered, crookedly, overall, to a secondary support of an unidentifiable material, –possibly be a fiber based board, all contained within a wooden oak frame, with a glass cover, and Masonite backing board.

I could see that it was constructed of 9 sheets of papyrus adhered, crookedly, overall, to a secondary support of an unidentifiable material, –possibly be a fiber based board, all contained within a wooden oak frame, with a glass cover, and Masonite backing board.

The view of the papyrus was obscured by a haze on the glass located about the areas of inscription. The secondary support: appeared to be composed of two pieces; the right is raised slightly more than the left. The papyrus itself showed areas of discoloration, delamination, loss, edge fray, cracking; faded media overall with areas of loss due friability and flaking of the pigment.

The view of the papyrus was obscured by a haze on the glass located about the areas of inscription. The secondary support: appeared to be composed of two pieces; the right is raised slightly more than the left. The papyrus itself showed areas of discoloration, delamination, loss, edge fray, cracking; faded media overall with areas of loss due friability and flaking of the pigment.

From this initial assessment we knew that we would need to address 1) The haze on the inner surface of the glass, 2) The secondary support and its lack of support, 3) Potential areas of loss on the papyrus, and 4) The backing materials.

2015 | Preparation for Digitization and Exhibit

We were expecting the glass to be loose, as you would find in a typical picture frame but it was not! Instead we found the glass held in place by a thinner inner frame nailed within the larger frame. This structure holds the glass in place and also keeps the papyrus from contacting the glass, but because of this the glass could not be removed.

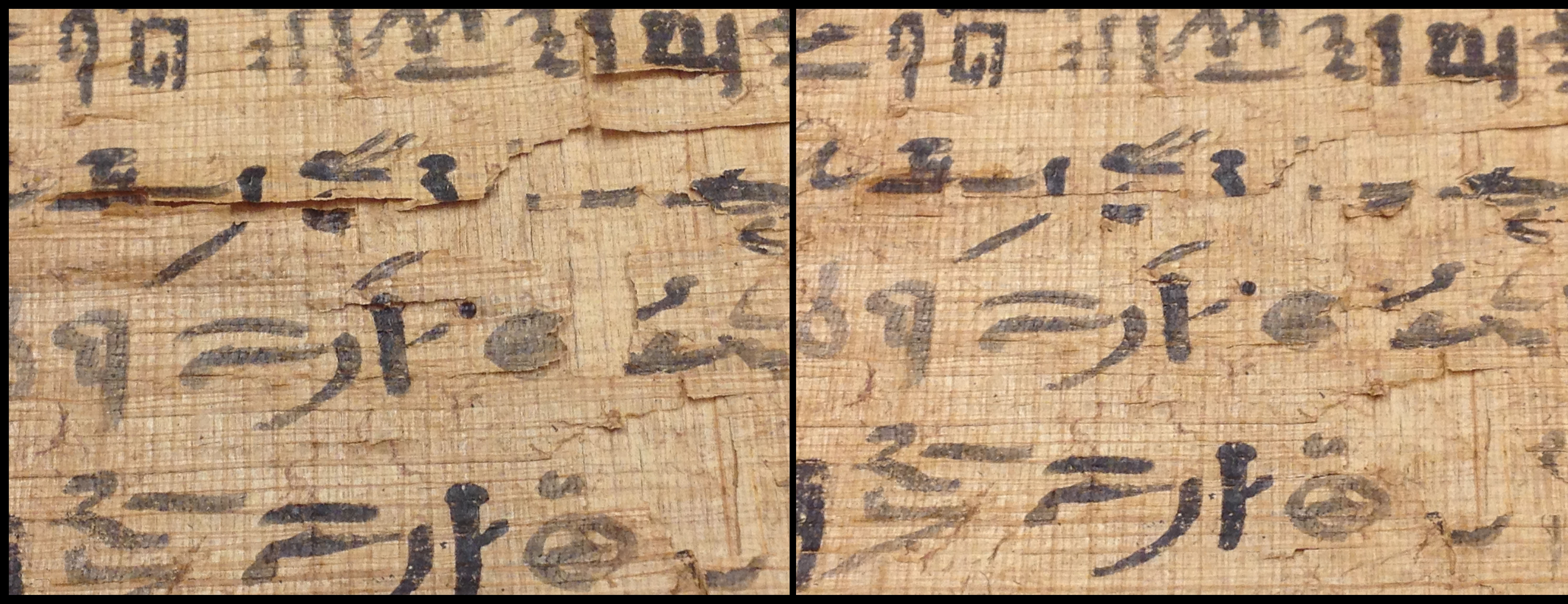

The haze on the inner surface of the glass was located above the areas containing the inscription. It was most likely caused by the migration of salts from the papyrus, pigments and/or mounting materials.

You can see the dramatic difference that cleaning made!

Now unframed, we were able to see how the papyrus was actually mounted. It was, as we thought, adhered crookedly overall to a secondary support, but that support was not a board. Instead, we found that the papyrus had been adhered to a now brittle paper support, which was then further adhered to a canvas support. This whole unit was then drummed around a wooden stretcher. The drumming is no longer taut and has a significant undulation at the left end which has transferred to the papyrus. This is a concern because it could potentially cause further cracking and fracture to the papyrus. Additionally, because it is drummed, the inner wooden stretcher is not in full contact with the papyrus (or the supports), only along the perimeter and along the center bar; it is not acting fully as a support to the papyrus.

Now unframed, we were able to see how the papyrus was actually mounted. It was, as we thought, adhered crookedly overall to a secondary support, but that support was not a board. Instead, we found that the papyrus had been adhered to a now brittle paper support, which was then further adhered to a canvas support. This whole unit was then drummed around a wooden stretcher. The drumming is no longer taut and has a significant undulation at the left end which has transferred to the papyrus. This is a concern because it could potentially cause further cracking and fracture to the papyrus. Additionally, because it is drummed, the inner wooden stretcher is not in full contact with the papyrus (or the supports), only along the perimeter and along the center bar; it is not acting fully as a support to the papyrus.

Returning to A.D. Whites Letters regarding the mounting system, frame, and shipping … He tells us it was “mounted to canvas on a wooden frame and securely packed under the direction of Bey (an eminent Egyptologist of the time). The glass I have taken out fearing that it might get broken and damage the papyrus, must be glazed again at Ithaca.”

As we have seen, the glass in the current frame is secured into the frame. Along with his letters, this tells us that it was not the original glass, and we know from Freddy’s research that the papyrus was re-framed sometime in the 1890’s. This was further confirmed by the nail markings we found in the inner frame around which the papyrus is drummed, as they do not line up with markings in the current frame. This means that the only part that is original is the inner wooden stretcher.

Notice that the nail marking in the inner stretcher to which the papyrus is mounted have no corresponding marking in the outer frame

TREATMENT

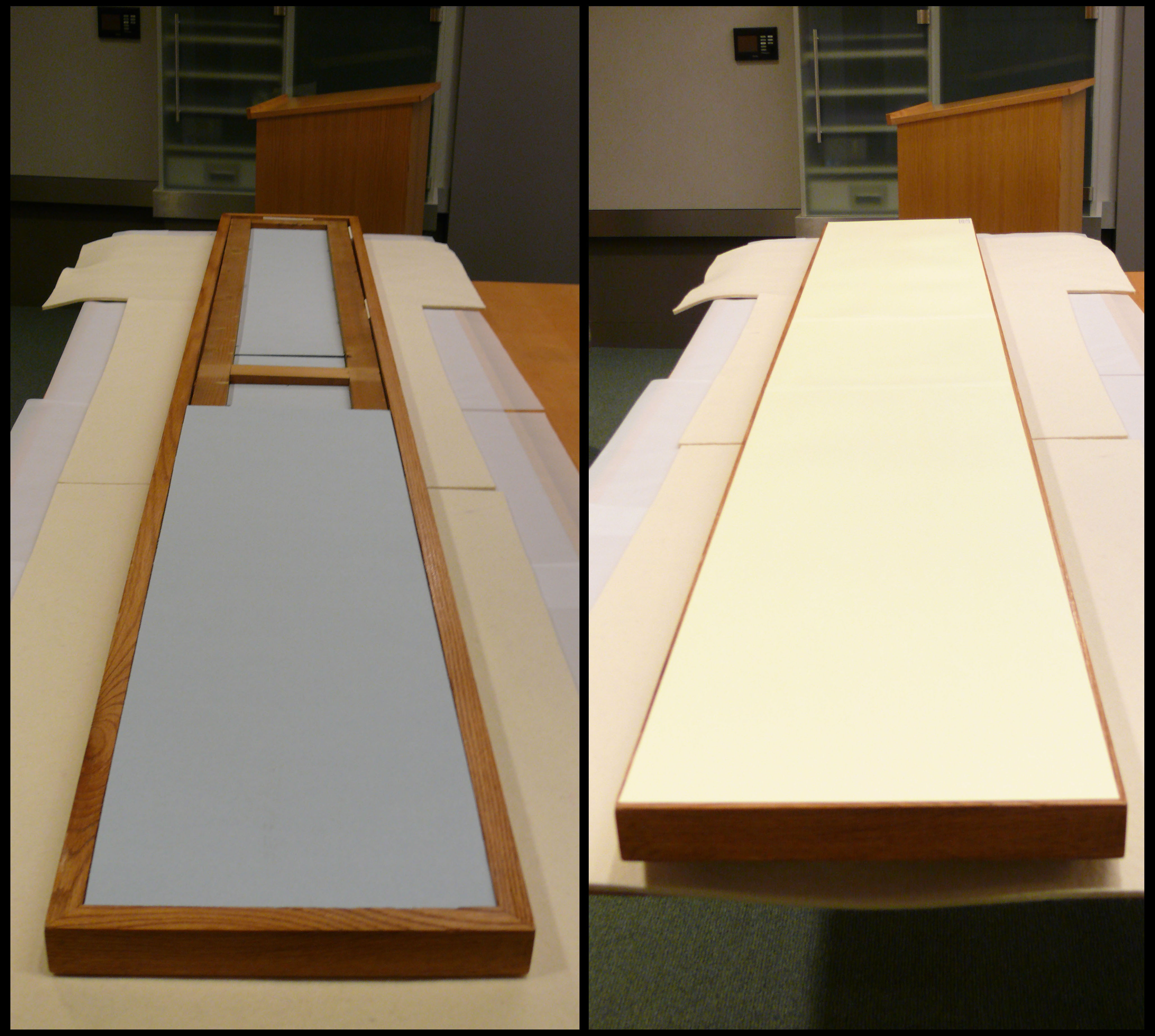

After these discoveries, one of the first treatment steps was reducing surface soil – dust, dirt, etc. from the item being treated. We used a HEPA-vacuum to remove the buildup of dust and dirt on the surface of the frame. Before we could work on the papyrus, we needed to address the lack of the support prior to stabilizing the front of the papyrus because the stabilization we would be doing to the front would involve drying mended areas under weight. A double layer of support system was fit into the inner stretcher to support the papyrus – the first 4-ply museum board, the second corrugated blue board. We hoped that this would provide enough support to the papyrus to reduce the stress caused by the undulation in the drummed support system.

For the purpose of digitization and the exhibit, we needed to address the areas of instability which would involve using some sort of adhesive to tack down papyrus edges that were frayed and pieces that were beginning to lift of flake. We found wheat starch paste would be best as it is reversible and would not discolor or further embrittle the papyrus.

For the purpose of digitization and the exhibit, we needed to address the areas of instability which would involve using some sort of adhesive to tack down papyrus edges that were frayed and pieces that were beginning to lift of flake. We found wheat starch paste would be best as it is reversible and would not discolor or further embrittle the papyrus.

The frame, likely because it is not the original, is a little big for the inner wooden stretcher around which the papyrus and secondary supports are drummed. When we unframed it, there were two small wooded shims at each end, but even then the inner frame was a little loose. To make it more secure in the frame we added new shims around the perimeter of the frame, then a backing board of blue corrugated board, and a 20 pt card dust cover.

The frame, likely because it is not the original, is a little big for the inner wooden stretcher around which the papyrus and secondary supports are drummed. When we unframed it, there were two small wooded shims at each end, but even then the inner frame was a little loose. To make it more secure in the frame we added new shims around the perimeter of the frame, then a backing board of blue corrugated board, and a 20 pt card dust cover.

The treatment so far has greatly improved the stability and appearance of the papyrus for the purposed of the exhibit and digitization. But there is still concern for the drummed mounting system. It is unlikely that removing the papyrus from the paper and canvas supports is an option. The fragility, brittleness, size, and overlapping joins of the papyrus makes removal from the secondary supports too much of a risk. We are currently researching a better overall support than the wooden stretcher it is drummed to now.