by Michele Brown

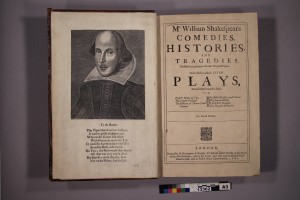

Cornell University Library is commemorating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death with a series of digital vignettes highlighting Cornell’s Shakespeare collection. Earlier this year, the Fourth Folio came to the conservation lab for treatment and evaluation.

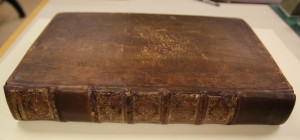

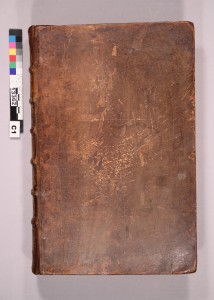

The binding on Cornell’s Fourth Folio appears to be contemporary with its 1685 printing date. It is a full calfskin binding with a gilt spine.The leather is tightly adhered to the back of the book (this is known as a tight back). When it came into the lab, the front board was detached, the back board was weakly attached, and a large piece of covering was missing from the back board. The tailband was mostly missing, with the core being held on with a few loops. The corners were worn with some losses. It had been previously repaired.

The front board of Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio, before treatment. Notice how the tailband is hanging off.

The tight bond between the original leather spine and the back of the book created difficulties for repairing the binding. Usually, when a book is rebacked the original spine is removed, the back is lined with cloth over tissue for strength and reversibility, and a new spine made from material similar to the original spine is applied. The original spine would then be stuck on over the new spine. The result is a book with reinforced sewing, new materials in all the areas that take the most stress, and yet with all of its original components retained.

The previous repair leather was applied only to the joints and head and tail caps, indicating perhaps, that the conservator had experienced difficulty removing the original spine.

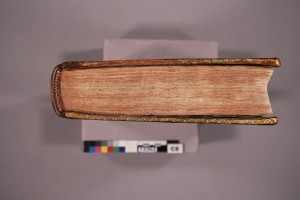

The spine of the Fourth Folio, before treatment. The repair leather is visible at the edges and head of the spine.

Since the spine of a tight back binding is adhered directly to the pages of the book, it is not always possible to remove the spine without damaging it or the pages. When a book is historically significant with a contemporary binding, it is important to retain as many of its original components as possible. That is the case with our copy of the 4th Folio. We can tell our copy was previously repaired not only by the “new” leather on the outside joints, but also by the treatment of the first few pages and the inner joints. We don’t know when the earlier repair was done, but the repair leather had deteriorated and needed to be replaced. The front board had become detached and needed to be reattached.

I tried lifting the original spine after first facing it with Hanji paper using methyl cellulose paste as the adhesive. I was able to remove the second panel (containing the title label), and the tail panel, but could only lift the edges of the rest of the spine. The edges of the boards, both inside and outside, were easily lifted.

Once the leather was removed from the second and last panels, these areas were first lined with usu mino tissue using wheat starch paste, and then with unbleached cotton stretch cloth (from Gane Bros) using pva. The stretch cloth was cut wide enough to stretch over onto the boards under the lifted leather. A lining of Conservation Wove paper (from Katie Macgregor), using pva, made for a nice smooth surface on these 2 panels.

Ideally, all of the panels would receive this kind of reinforcement, but the spine adhesion was tenacious. How could I add strength to my repair? I decided to use joint tacketing on the front board. Joint tacketing consists of drilling several holes into the joint, angled so they come out on the shoulder of the spine. Two corresponding holes for each tacket are drilled into the board. Linen thread is passed through the joint to the spine and secured with a loop. The tails pass through the holes in the board. A square knot is tied to hold the threads in place. This holds the board to the spine in a way that is similar to its original attachment. The joint tacketing link above provides a detailed description of the procedure.

Before drilling the holes, a strip of Hanji paper was attached to the inside shoulder, one edge aligning with the shoulder, the rest extending towards the fore edge. This would be folded up over the linen thread loops towards the end of the treatment. Then, holes at 5 stations were drilled into the joint and 2 per each station were drilled into the board. At each station, the thread was passed through the shoulder, looped, and then passed through the board and tied in a square knot.

A new tailband was woven using silk twist over the original tailband core.

New calfskin (from Hewit’s) was pared, dyed and attached to the second and bottom panels, extending across the spine and onto the boards. New calfskin strips were also added to the headcap and joints under the lifted spine edges and onto the boards under the lifted sides. The lifted board material was put down with wheat starch paste.

The corners were repaired with dyed calfskin or colored tissue. The Hanji strip in the front inner joint was pulled across the joint and adhered under the lifted paste-down with paste. Then, it was covered with CK color kozo. The back joint was also covered with CK color kozo. Wheat starch paste was used for these steps.

The finished front inner joint. Losses on the fly leaf were replaced with color kozo from Hiromi, using paste.

The lifted spine panels and edges of the spine were re-attached using wheat starch paste. This hid the tacketing threads on the shoulder. The corners were repaired with dyed calfskin and toned kozo. The loss on the back board was patched with dyed calfskin.

As a result of this treatment, the book is much stronger and more easily handled. If the repair leather fails, the tackets should help keep the front board attached. The cloth liners across the 2 panels that were lifted will also provide extra support.

One of our goals in the conservation lab is to make the physical collections accessible for study and analysis. Here’s hoping that readers of Shakespeare will be able to enjoy Cornell’s copy of the Fourth Folio for another 400 years!