By Rachel Mochon

Chemistry and The College Scholar Program

Cornell University Class of 2016

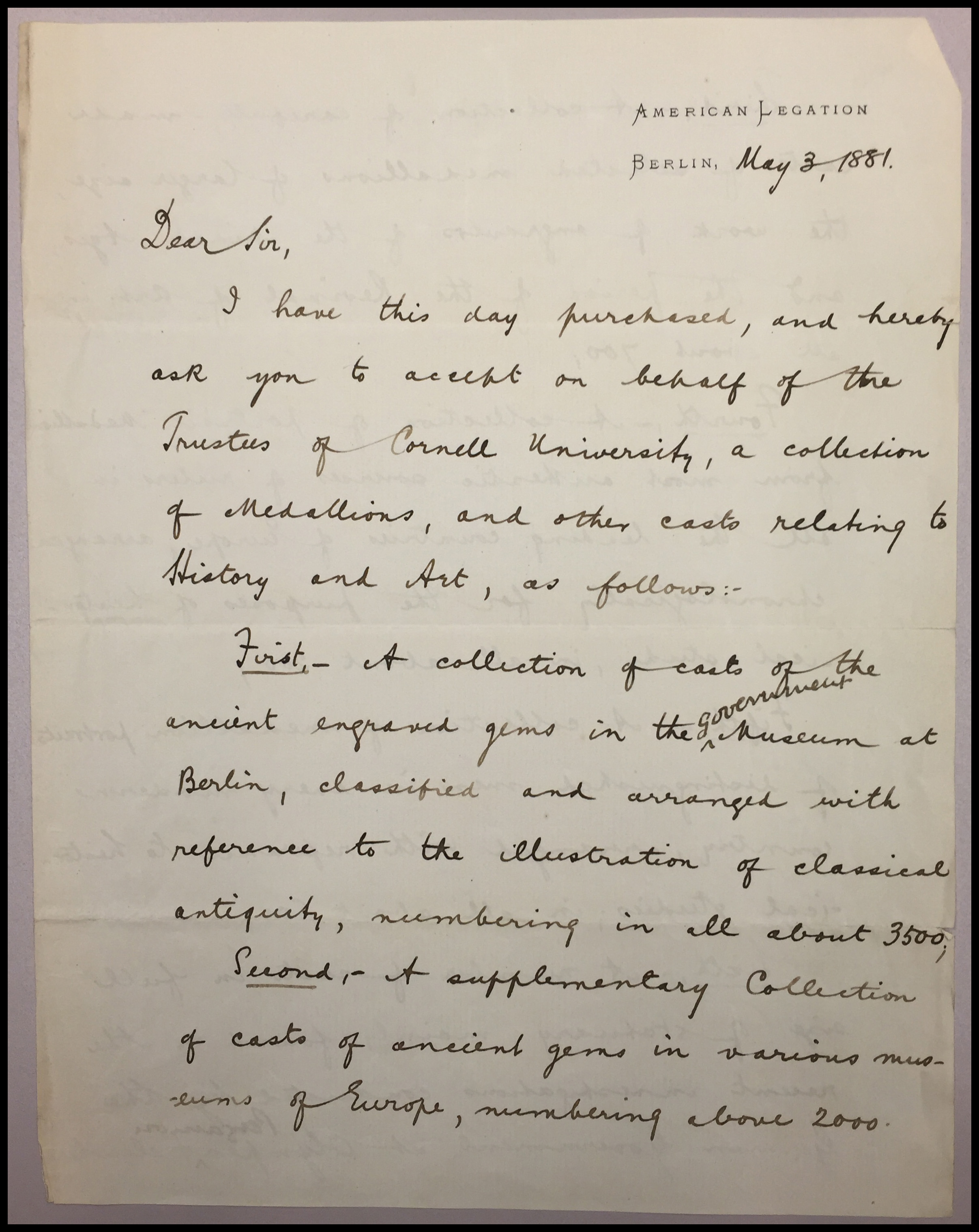

In 1881, Andrew Dickson White, Cornell’s first president, gifted several significant collections to the university “…as a slight token of continued interest in the educational work of our country and our own state, as also of devotion to classical studies and culture…” These collections include 19th century architectural photographs, large plaster casts of statuary, plaster gems, and plaster casts of Renaissance and Medieval medallions.

In 1881, Andrew Dickson White, Cornell’s first president, gifted several significant collections to the university “…as a slight token of continued interest in the educational work of our country and our own state, as also of devotion to classical studies and culture…” These collections include 19th century architectural photographs, large plaster casts of statuary, plaster gems, and plaster casts of Renaissance and Medieval medallions.

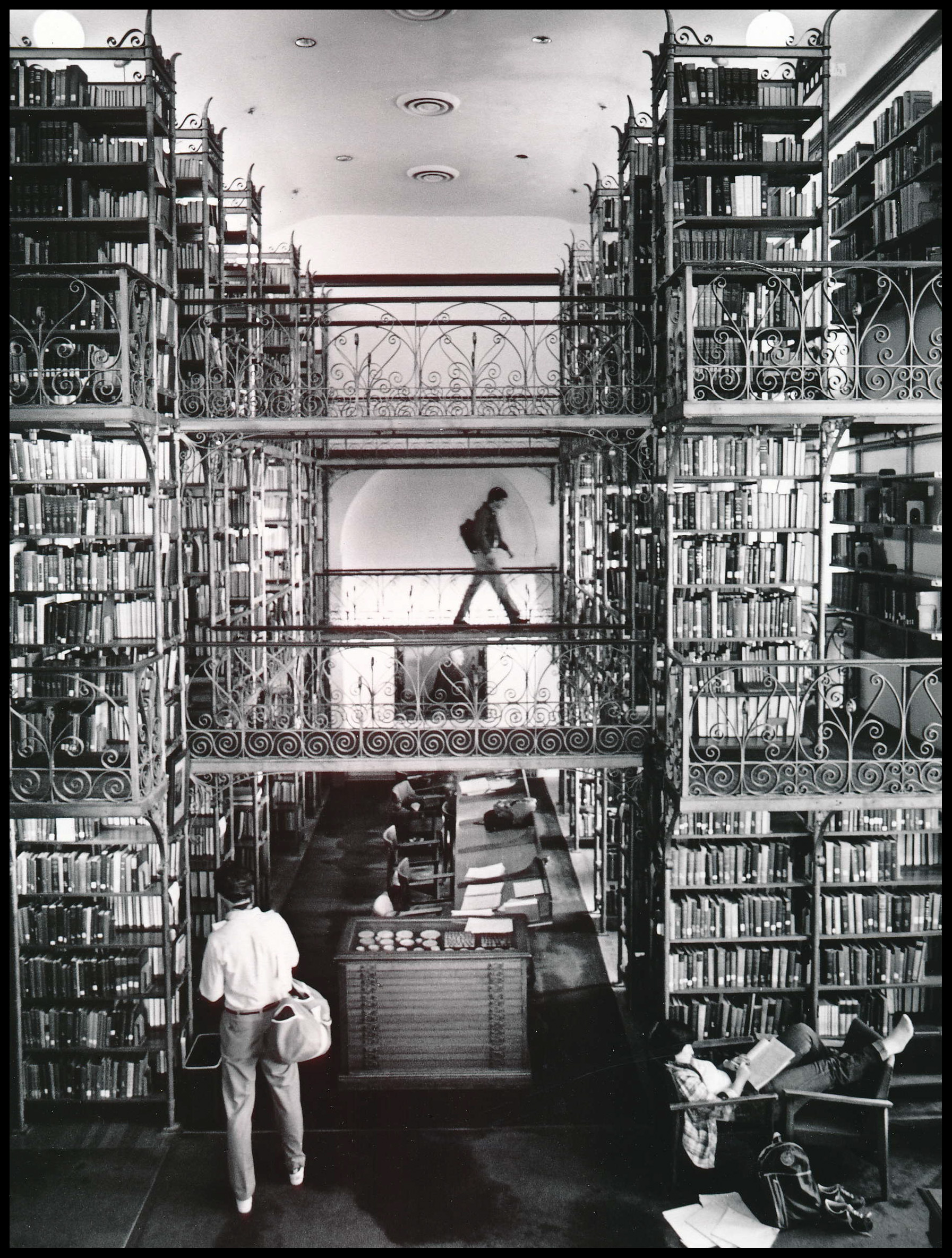

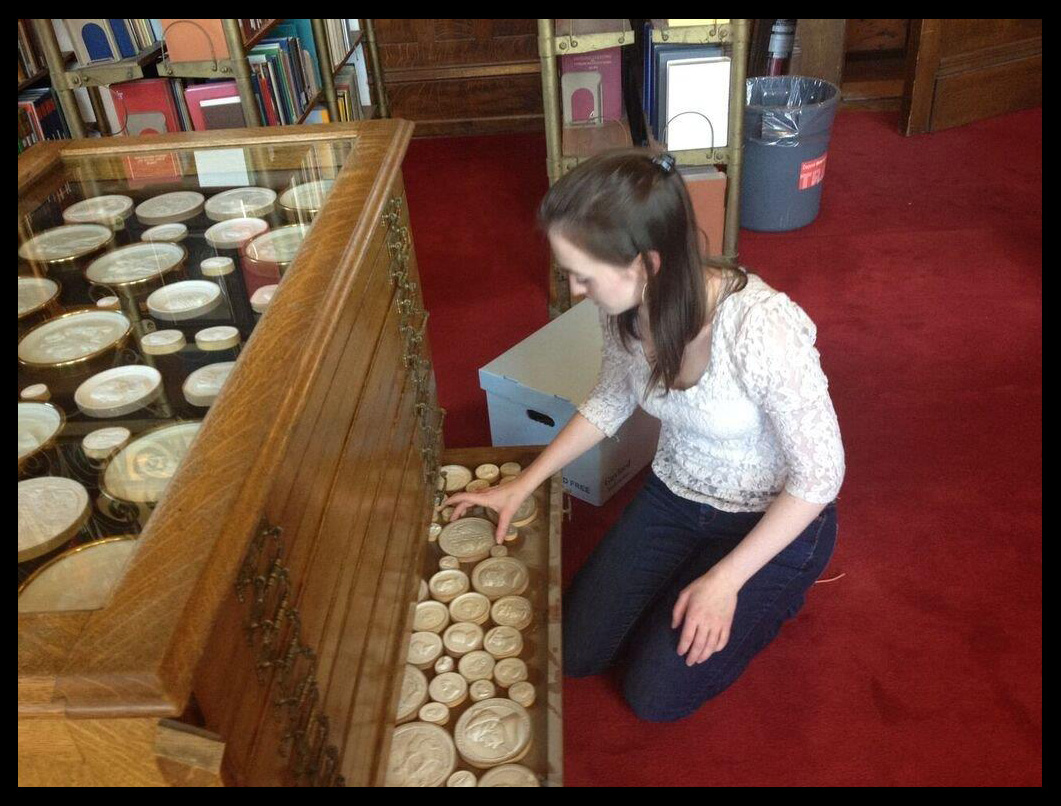

The plaster cast medallions were stored for over 100 years in locked wooden cabinets in the A.D. White Library in Uris Library. The A.D. White Library is currently undergoing renovations as a result of a highly successful crowdfunding campaign to Bring Light to the A.D. White Library. For the renovation, the two wooden display cabinets will be relocated, requiring the removal of the plaster cast medallion collection.

The collection is being transferred to the Rare and Manuscript Collections where it will join the plaster gems already stored there. With the transfer to RMC, the collection will have improved cataloguing and access and will now be available for research and exhibit use. However, before the medallions could be available for research and use, their significant condition concerns needed to be addressed.

The medallions were not organized in the display cabinets by content or size, nor were they easily accessible for study in the locked cabinets. Heavy amounts of disfiguring dust and dirt settled on the medallions, particularly those near the front of the drawers, which obscured the features and damaged the soft plaster.

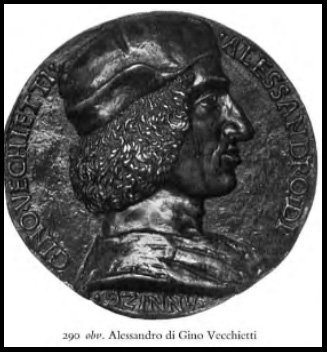

The plaster cast medallions are made from plaster, a mixture of powdered gypsum and water. The plaster surfaces were all relatively soft, so the medallions scratch easily. Most of the medallions are circular and vary in size from quite small (the size of a U.S. quarter) to the largest of 10 cm in diameter. Other medallions are shaped like ovals or rectangles with rounded corners. Every medallion is made of white plaster with a brown paper ring around the edge. Many of the paper rings are painted gold along the top edge. The image of the figure is in the center of the medallion with his or her name around the top or bottom of the portrait. Although many of the portraits are in profile, which originated from ancient coins, many of the plaster portraits depict the personage’s full face directly or only three-quarters of the face. A number of the portraits are cast in high relief that reflects light to evoke expressiveness. However, this three-dimensionality varies too. Many of the plaster medallions are quite flat, especially among those that are of the most common size, 7 cm in diameter. Nevertheless, the texture and patina of the plaster is critical to the viewing experience.

The plaster casts were made from existing metal medallions, including Renaissance medals from as early as the 15th century. For example, the A.D. White collection includes a medallion of Alessandro di Gino Vecchietti, born on October 2, 1472, that was cast from a bronze medal that dates to approximately 1498.

The major condition concern with the medallions was the heavy layer of damaging and obscuring dust and dirt. In addition, some medallions had broken paper rings and some had chips, breaks, old repairs, or were fully broken.

The Alessandro di Gino Vecchietti medallion shows the improvement by surface cleaning.

The first step in the conservation treatment was surface cleaning to remove the disfiguring films of dirt and dust on the surfaces of the medallions. Because the plaster surfaces are soft, various cleaning methods were investigated to determine what would be the most effective and least harmful method of cleaning. After seeking advice from objects conservators, a HEPA vacuum cleaner, hard and soft bristle brushes, soot sponges, cosmetic sponges, and vinyl erasers were all tested to remove dust and dirt. The combination of the HEPA vacuum, vinyl erasers and a soft bristle brush were determined to remove the most disfiguring dirt without scratching the surface.

In addition to surface cleaning, the paper rings on several medallions had torn or two edges had separated where they were originally adhered together. The bands are adhered to the plaster in only one location along the rim, and the remaining paper is wrapped around tightly and secured to itself. To repair broken rings, wheat starch paste and toned Japanese tissue paper were used. In the case of a medallion where the original attachment of two ends had failed, paste was applied with a brush to the underside of the flap that lays on top of the other end of the band. This was then secured with a bridge of toned Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste on the exterior of the band. In the case of a medallion with a torn band, a bridge of toned Japanese tissue was applied underneath the band edges and adhered with wheat starch paste.

In addition to surface cleaning, the paper rings on several medallions had torn or two edges had separated where they were originally adhered together. The bands are adhered to the plaster in only one location along the rim, and the remaining paper is wrapped around tightly and secured to itself. To repair broken rings, wheat starch paste and toned Japanese tissue paper were used. In the case of a medallion where the original attachment of two ends had failed, paste was applied with a brush to the underside of the flap that lays on top of the other end of the band. This was then secured with a bridge of toned Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste on the exterior of the band. In the case of a medallion with a torn band, a bridge of toned Japanese tissue was applied underneath the band edges and adhered with wheat starch paste.

The medallions are fragile and several show old glue repairs to reinforce breaks and cracks. In the past some medallions were left un-repaired.

In the inventory photo below from the 1980s, you can see the medallion on the left is broken, and it remained broken for 30 more years.

To repair broken medallions, the pieces were first thoroughly cleaned using vinyl erasers and a soft bristle brush. A stable, conservation adhesive with good strength and dries clear, was then chosen to secure the medallion pieces to one another. The adhesive was applied to all edges of all the pieces first as a protective layer. Without this layer, the adhesive would be absorbed into the plaster’s pores and the mend between two pieces would not be as strong as it could be. After the protected layers were allowed to dry, another coat was used to adhere pieces together.

To repair broken medallions, the pieces were first thoroughly cleaned using vinyl erasers and a soft bristle brush. A stable, conservation adhesive with good strength and dries clear, was then chosen to secure the medallion pieces to one another. The adhesive was applied to all edges of all the pieces first as a protective layer. Without this layer, the adhesive would be absorbed into the plaster’s pores and the mend between two pieces would not be as strong as it could be. After the protected layers were allowed to dry, another coat was used to adhere pieces together.

After treatment, the medallions were organized by size and housed in archival paper board boxes. Several trays, made from acid-free board, can fit in each box, and, depending on size, on average each tray can fit up 8-24 medallions, separated by acid free paper and/or foam.

By the end of the project over 1500 plaster cast medallions had been cleaned, stabilized and rehoused. I learned about the variety of materials that can be used to safely surface clean plaster and was able to determine what would work best for the soft, porous, plaster surfaces of these medallions. Rehousing the medallions was like a jigsaw puzzle—determining how to effectively and efficiently house the medallions securely without expanding the size of the collection! During the course of this project, I also learned about how historic teaching collections were used in instruction and how they can continue to be valuable assets in today’s learning environment. Because of this project, A.D. White’s collection of medallions will once again be used as a teaching collection for Cornell University students and researchers.