by Michele Brown

The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude was formally passed by Congress on January 31, 1865 and ratified by the states December 6, 1865.(1) Cornell University Library owns one of the 15 copies signed by Lincoln. Cornell’s copy of the 13th Amendment is a “Congressional copy” and was donated to the University by the Nicholas H. Noyes family in the 1950s.

Like other important documents, the 13th Amendment is written on parchment. Parchment is a writing material made from animal skin that’s been dehaired, soaked in lime, scraped and stretched. We will have another post specifically about parchment production. Some types of paper are also referred to as parchment, but it would be more accurate to describe them as “parchment-like.” See here for descriptions of parchment, vellum and parchment paper. Parchment has long been used for important documents because it is considered to be the most permanent and stable writing material.

2014 was an eventful year for Cornell’s copy of this important document. In April, it was removed from its 20th century frame and scanned using hyperspectral imaging.

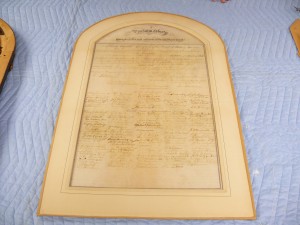

This gave us an excuse to examine the matting and framing materials supporting our copy of the 13th Amendment. Cornell’s copy is housed in an elaborately carved wooden frame. A decorative headpiece with the words “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land, and unto all the inhabitants thereof” was attached to the document at some point. From the label on the back of the frame we assume the document was put into this frame in 1938 by Beard Art Galleries.

We were concerned that the document seemed to be unnaturally flat within the frame and we wondered how it had been attached to the backing board.

After the framed document was brought into the Conservation Lab, the hanging hardware was removed and the paper covering the back of the frame was lifted off.

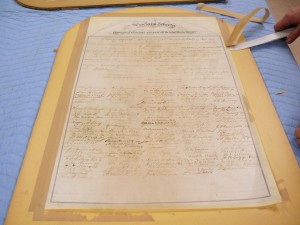

We could see the document and its matting were sealed in a package that was held in the frame with nails. The nails were removed and the package was lifted out of the frame.

The document and matting were sealed together with brown paper packing tape, which was removed mechanically. We discovered that the decorative mat was glued lightly to the window mat below it.

The document had been taped to the backing board with the same brown paper tape. This tape was also removed mechanically.

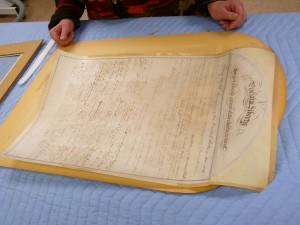

Now, we could see that the document was stuck directly to the backing board. This was a common method for controlling parchment, but it is not good for the document. Parchment needs to be able to respond to changes in humidity. If it is constrained too tightly while experiencing changes in humidity, it may split. Fortunately, it was easily lifted off the backing board, although first we had to remove the staples!

When the document was free of the backing board we could see that it wanted to curl. We could also see that the headpiece was cut from thinner parchment than the document itself.

There was a residue of glued paper tape around the edges of the document and the headpiece. This residue was removed mechanically and by lightly rubbing with damp cotton.

In order to humidify and flatten the document, we decided to separate the two pieces.

After humidifying each piece, we dried them on a suction table before putting them between boards.

They were allowed to dry for several weeks and then were reattached using hot gelatin.

Now, we had to decide how to re-mat the document.

For the reasons stated above, we did not want to re-attach the document directly to the backing board. Instead, parchment documents are often attached to the backing board of a mat by using pieces of string that have been attached to the document and which are then wrapped around to the back. After careful consideration we decided to instead use strips of Japanese tissue. This method was described by Nicholas Pickwoad in The Paper Conservator (2). The tissue strips were attached to the back of the document using stiff wheat starch paste and then attached to the back of the board. This will allow the document to expand and contract as needed due to changes in the relative humidity. If the humidity becomes too low, the paper strips will break rather than the parchment itself splitting. We decided to use usumino (thick) tissue from Hiromi Paper for the strips.

We constructed a new backing board by laminating 3 layers of archival mat board cross-grained, with the short grain piece in the middle and using wheat starch paste as the adhesive.

Because the humidity in the conservation lab was relatively low, we moved the the document to the Kroch vault to attach the document to the backing board. The vault has a better humidity for parchment and it is where the document will spend most of its time. This allowed us to apply tension to the strips while the parchment was in a relaxed state.

The front of the document. The strips attached to the back of the document, but not to the front of the board.

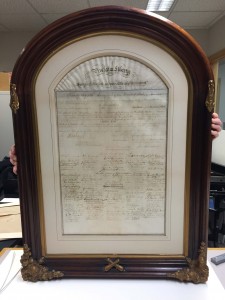

Ariel Ecklund of Corners Gallery in Ithaca cut a new window mat from archival mat board and then reassembled the document with its new mat and its original decorative mat back into the frame. She replaced the 1930’s glass with museum glass. She added thickness to the original frame to provide better attachment for the framing points.

The document doesn’t look as flat as it did before, but it is now surrounded by acid-free, archival materials and it can flex as necessary.

The Thirteenth Amendment is part of the new exhibit, “Abraham Lincoln’s Unfinished Work”, which will be in the Kroch Library from January 26, 2015 until September 30, 2015. The original copy of the Thirteenth Amendment will be on display at selected times. Check the the library website for those dates.

(1) Library of Congress. Thirteenth Amendment. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/13thamendment.html

(2) Pickwoad, Nicholas. (1992). “Alternative Methods of Mounting Parchment for Framing and Exhibition”. The Paper Conservator. 16(1), pp. 78-85.