By Michele Hamill

August 2015 marked the 30th anniversary of the Cornell Library’s conservation program. The traditional gift for a 30th anniversary is a pearl–a gemstone of great beauty, and a term meaning something rare, fine and valuable. We’ve had three gifts– three very fine directors–in our 30 years. Tre Berney, Barbara Berger Eden, and John Dean are each a pearl in their own right.

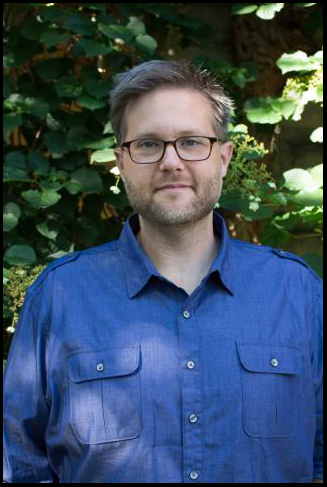

It is with great pleasure that we welcome Tre Berney as Director of Digitization and Conservation Services. (Interesting note: Tre hails from Tennessee—whose state gem is the pearl and has the only freshwater pearl cultivation outside of Asia!). This new position was created to provide leadership for both Preservation and Conservation Services and the Digital Media Group.

It is with great pleasure that we welcome Tre Berney as Director of Digitization and Conservation Services. (Interesting note: Tre hails from Tennessee—whose state gem is the pearl and has the only freshwater pearl cultivation outside of Asia!). This new position was created to provide leadership for both Preservation and Conservation Services and the Digital Media Group.

Tre has been at Cornell for almost 3 years developing and implementing AV digitization workflows to preserve Cornell University’s unique A/V holdings and digital collections. He designed and established a digitization lab to digitize fragile recordings and older legacy formats. Tre and Library colleagues just completed a campus-wide A/V census, the first of its kind at Cornell, as part of a larger A/V initiative partnering the library with Cornell IT to inform a preservation strategy for those formats at imminent risk of degradation, loss and obsolescence. He works closely with Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology, Indiana University, Audio/Visual Preservation Solutions, Syracuse University, UCLA, Columbia and the Library of  Congress. His work in A/V preservation ensures that Cornell’s unique assets in the form of lectures by faculty, Nobel Laureates, writers and artists, and original source recordings used in research in biology, linguistics and art will be available in the future.

Congress. His work in A/V preservation ensures that Cornell’s unique assets in the form of lectures by faculty, Nobel Laureates, writers and artists, and original source recordings used in research in biology, linguistics and art will be available in the future.

Tre brings a wealth of skills and experiences to this position along with energy, enthusiasm and appreciation for the Library’s collections and the work we do in the conservation program. We’re excited to have Tre leading our program and look forward to collaborating to preserve the many formats that comprise the Library’s collections.

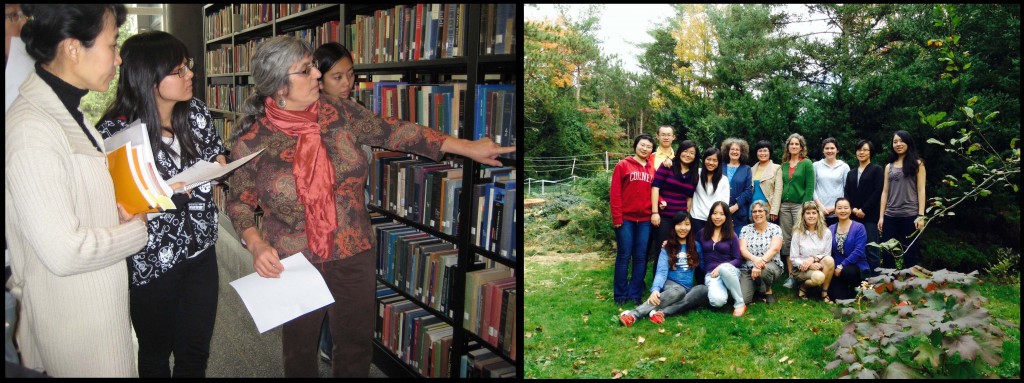

We are also celebrating Barbara Berger Eden and her significant contributions to Cornell Library as she retires this week after 30 years of service. In Barbara’s tenure at Cornell Library, she served several key roles including manager for ambitious microfilming projects, grants officer, and Principal Investigator for successful grants including Save America’s Treasures and the Henry Luce Foundation Chinese Librarian Preservation Training Initiative which strengthens Cornell Library’s relationship with our partner libraries in China by fostering exchange between the academic library communities in the United States and China. Due to Barbara’s efforts, the preservation capability across China has been expanded and important materials for teaching and research are being preserved.

We are also celebrating Barbara Berger Eden and her significant contributions to Cornell Library as she retires this week after 30 years of service. In Barbara’s tenure at Cornell Library, she served several key roles including manager for ambitious microfilming projects, grants officer, and Principal Investigator for successful grants including Save America’s Treasures and the Henry Luce Foundation Chinese Librarian Preservation Training Initiative which strengthens Cornell Library’s relationship with our partner libraries in China by fostering exchange between the academic library communities in the United States and China. Due to Barbara’s efforts, the preservation capability across China has been expanded and important materials for teaching and research are being preserved.

As director of Preservation and Conservation Services since 2005, Barbara led the conservation program through times of great change in academic research libraries with insight, advocacy, and collegiality. As a result, our conservation program has thrived, with dedicated staff with deep expertise and the resources to preserve Library collections in their original format.

Barbara is th e past chair of the Preservation and Reformatting Section of the American Library Association and has been an active member of the Preservation Administrators Group of the New York State Comprehensive Research Libraries. Barbara has served as a wonderful mentor to several Library staff as part of the Library’s Mentoring Program sharing her wide experience, knowledge, and perspective to foster the professional growth of our colleagues. We are deeply appreciative of Barbara’s efforts on our behalf and her thoughtfulness, generosity and support. We wish her a healthy, happy retirement filled with good gardening, family and friends. She will be missed.

e past chair of the Preservation and Reformatting Section of the American Library Association and has been an active member of the Preservation Administrators Group of the New York State Comprehensive Research Libraries. Barbara has served as a wonderful mentor to several Library staff as part of the Library’s Mentoring Program sharing her wide experience, knowledge, and perspective to foster the professional growth of our colleagues. We are deeply appreciative of Barbara’s efforts on our behalf and her thoughtfulness, generosity and support. We wish her a healthy, happy retirement filled with good gardening, family and friends. She will be missed.

John Dean became Cornell University Library’s first conservation and preservation librarian with the establishment of the program in 1985 and served as director for nearly 20 years before retiring in 2003. John’s background, including a 6-year apprenticeship in bookbinding in his native England, some years spent as journeyman bookbinder, leadership of preservation programs at the Newberry Library and Johns Hopkins University, and two graduate degrees (in library science and in liberal arts with a concentration in the history of science), made him a rare and valuable combination of an effective administrator, master bookbinder, and consummate conservator.

John Dean became Cornell University Library’s first conservation and preservation librarian with the establishment of the program in 1985 and served as director for nearly 20 years before retiring in 2003. John’s background, including a 6-year apprenticeship in bookbinding in his native England, some years spent as journeyman bookbinder, leadership of preservation programs at the Newberry Library and Johns Hopkins University, and two graduate degrees (in library science and in liberal arts with a concentration in the history of science), made him a rare and valuable combination of an effective administrator, master bookbinder, and consummate conservator.

As director of the department, John brought a profound knowledge and deep regard for collections in all formats and instilled an appreciation for fine craftsmanship grounded in professional standards for conservation. He mentored and taught at the local, national and international levels. In 2003 John was the recipient of the prestigious Association for Library Collections & Technical Services Paul Banks & Carolyn Harris Preservation Award for his significant contributions to the field.

John remains passionate about preservation and conservation and has endeavored to help institutions around the world through education, training and consultancies in developing countries, such as Laos, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, Java, and Cambodia. He created seminal online tutorials for library conservation and preservation in Southeast Asia, Iraq and the Middle East to give librarians and archivists in these and other countries a set of basic guidelines to inform their preservation efforts. In retirement John continues to assist local institutions care for their book collections. John’s legacy has had a lasting impact on the preservation and conservation field, on Cornell University Library, and on those of us who had the honor and privilege of working with him.

John remains passionate about preservation and conservation and has endeavored to help institutions around the world through education, training and consultancies in developing countries, such as Laos, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, Java, and Cambodia. He created seminal online tutorials for library conservation and preservation in Southeast Asia, Iraq and the Middle East to give librarians and archivists in these and other countries a set of basic guidelines to inform their preservation efforts. In retirement John continues to assist local institutions care for their book collections. John’s legacy has had a lasting impact on the preservation and conservation field, on Cornell University Library, and on those of us who had the honor and privilege of working with him.

Where will we be in the next 30 years? Undoubtedly, there will be new challenges, formats, and discoveries. Thanks to our 3 distinguished directors, Tre, Barbara, and John, Cornell Library’s conservation program is ready to serve the preservation and conservation needs of the Library well into the future. A sincere thank you to Oya Rieger, Associate University Librarian, for her leadership, vision, and support of our program. Stay connected with us on our Facebook page and on this blog for updates on our many projects and for some pearls of wisdom for caring for library collections.