J.M. Iacchei

We thought it a fitting time of year to highlight Cornell Library’s world class Witchcraft Collection, specifically the Witchcraft in Popular Culture subdivision.

Those of you familiar with Harry Potter may recognize Reparo as the Mending Charm:

“The Mending Charm will repair broken objects with a flick of the wand. Accidents do happen, so it is essential to know how to mend our errors.

– from the Book of Spells, (http://harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/Mending_Charm)

With hundreds of vintage movie posters, movie stills, and promotional materials depicting Witchcraft in Popular Culture (including Harry Potter movie posters and memorabilia) a mending charm in the Conservation Lab would be put to good use!

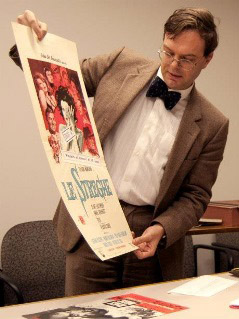

Laurent Ferri, Curator, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (RMC), is leading the initiative to expand the Witchcraft Collection begun at Cornell in the late 19th century to encompass “Witchcraft in Popular Culture.”

Laurent Ferri, Curator, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (RMC), is leading the initiative to expand the Witchcraft Collection begun at Cornell in the late 19th century to encompass “Witchcraft in Popular Culture.” Laurent kindly provided a brief overview of this collection, its significance to scholarship, and importantly, the reason as to why it was necessary to branch out from the original collection, mostly 17th and 18th century bound volumes, into the new terrain of popular culture.

Here are a few words from Laurent:

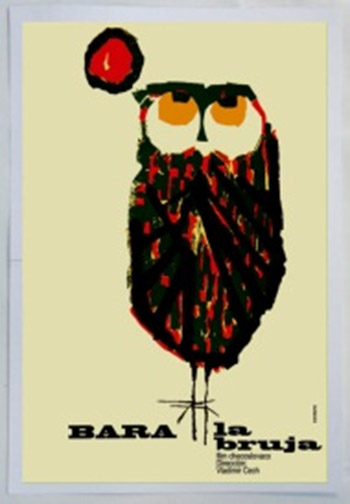

Since 2012, we have assembled a unique and spectacular collection of approximately 490 pieces of vintage witchcraft-and possession-related movie material covering the period from 1916 through 2015 — that is, 99 years of outstanding material documenting the cultural impact of witchcraft and possession through the history of world cinema.

This is the perfect complement to the Witchcraft Collection started by A.D. White in the 1880s, as today affordable demonology treaties and witchcraft trial records appear less frequently on the market, and more researchers choose popular culture as their field of inquiry.

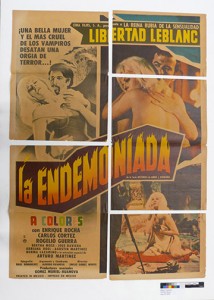

Numbered #4781 in RMC, “Witchcraft- and Possession-Related Movie Posters, Lobby Cards, and other Cinema Memorabilia, 1916-2015” is a great resource for the study of the rich iconography of witches. It also offers an opportunity to reflect on film genres and sub-genres as defined by the film industry, critics, and censors (“horror film”, “nunsploitation film”, “adult movie”, etc…). Given the graphic imagery and permanent recycling of erotic stereotypes, it could be used in conjunction with Cornell’s vast Human Sexuality Collection as well.

These striking, colorful, and often very large items are gradually making their way to the conservation lab for treatment – cleaning, pressure sensitive tape removal, stabilization of weakened or torn areas, and humidification and flattening prior to storage. Overall, these items are of great variety in both their physical characteristics (dimension, support, and condition) as well as their artistic and graphic styles.

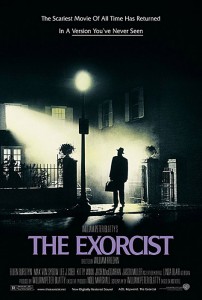

Laurent also points out the significant aesthetic quality of the collection “…movie poster design is an art, sometimes. Take, for instance, Bill Gold, who worked in the art department of Warner Bros and produced more than 1,000 posters until his retirement in 2004. The poster for “The Exorcist” (1973) serves its purpose perfectly: it points to the tradition of the American “film noir”, and it is inviting but not a spoiler. Another “masterwork” is the minimalist and eerie poster for “Rosemary’s baby” (1968)…the president of the advertising company Young and Rubicam, Stephen Frankfurt (a kind of Don Draper in “Mad Men”) is often credited with the choice (and, perhaps, the idea).”

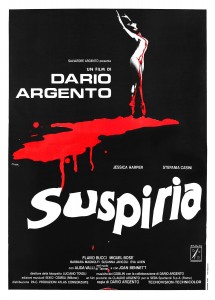

Another masterwork of poster art is “…Giuseppe Bassan’s poster for “Suspiria” (1977), which is reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley’s decadent illustrations for Salome (1893) — they both evoke what’s been termed by some art historians “aesthetic Satanism”.

Here is one example of a treatment carried out for this collection:

The poster below was printed on a wood pulp paper. Overtime it had become increasingly brittle and discolored from acid degradation. It had also, at one time, been stored folded leaving extremely fragile and weakened areas along the folds. As you can see, it became separated along the folds into five frail pieces.

Left: Before Treatment; Right: During Treatment, blotter washing

Each individual piece was blotter washed (to provide support during aqueous treatment when the wood pulp paper is extremely fragile), flattened, and dried underweight before being pieced back together with a thin Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste. This treatment reduced the acidity and brittleness of the paper support, making handling much less precarious. In a more stable condition, this is one of the many items of the Witchcraft in Popular Culture collection now accessible for use.

Or maybe I just said “Charta Reparo!”

Above: After Treatment

More information about the Cornell University Witchcraft Collection can be found here: http://digital.library.cornell.edu/w/witch/

Also of interest is a current exhibit, co-curated by Laurent, at the Johnson Museum of Art, Surrealism and Magic. More about the exhibit can be found here: http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/surrealismandmagic/