by Michele Brown

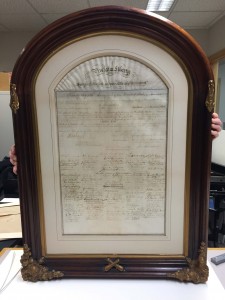

Parchment is a tough, long-lasting writing and book covering material used historically for important documents and still used for the transcription of some religious and government laws. Consequently, Cornell’s copy of the 13th Amendment was written on parchment. My previous post described its conservation treatment.

Legend has it that parchment was developed in the kingdom of Pergamon during the second century BC as a result of a shortage of papyrus. (1) Scholars disagree on the reason for the shortage of papyrus, but it is widely accepted that parchment production was first refined in Pergamon, which became parchment’s namesake. Parchment-making has remained largely unchanged since its early beginnings.

Sometimes the term “vellum” is used for parchment. Vellum, to be precise, is parchment made from calfskin. The terms parchment and vellum are now often used interchangeably.

How does parchment differ from leather since they are both made from animal skins?

Most leather is made from animal skin that has been treated with tannin. This changes the collagen of the skin so that it will be more durable. Since tannins are acidic, leather is also an acidic material.

Some skins are tawed rather than tanned. Very early books bound in Europe were often bound with alum-tawed leather. We will discuss tawed leather in another post.

Parchment is made by soaking an animal skin (usually from a goat, sheep or calf) in lime and then stretching it on a frame, scraping it to remove excess tissue and allowing it to dry under tension. During this process, the collagen of the skin is rearranged, but not chemically altered. The result is a material that is very smooth and hard, and also very sensitive to changes in humidity. Since it has been soaked in a solution with a high pH, it is basic.

Pergamena has been making leather and parchment for generations and has offered parchment-making workshops. The following images are from one of their workshops.

Skins arrive with their fur still intact. They have been salted to preserve them.

First, they are “de-haired”.

And then allowed to drain.

Excess flesh is removed, in this case, using a fleshing machine. Traditionally, they would have used a two handled knife.

On this day, we were making colored goatskin parchment so at this point the skins were dyed.

And then, clipped to a frame to dry under tension.

These are skins of dyed goatskin parchment drying under tension. The screen allows airflow on both sides of the skins.

The skins for calfskin parchment were treated differently. Since they weren’t being dyed, they were allowed to dry and were re-hydrated before being stretched for scraping.

Once the skins were stretched and clipped, they were scraped to make them thinner. Parchment-makers use a curved knife called a lunellum for this purpose.

The skins may be sanded after scraping.

Once the skin has been scraped so it is thin and even, it can be used for writing or binding.

Parchment can be difficult to work with because it has a hard surface and, depending on its thickness, can be somewhat inflexible. It is extremely sensitive to changes in humidity and using adhesives can be problematic. However, it is a beautiful and resilient material and with good care will last for centuries.

(1) In Natural History, Book XIII, Pliny ascribes the cause of the papyrus shortage to the rivalry between King Ptolemy V, who was building the library of Alexandria and King Eumenes II, who was building the library at Pergamon. Some sources say that King Ptolemy cut off the papyrus supply to Pergamon, forcing it to come up with an alternative source of writing material.

I’ve read that Gutenberg printed 20 bibles on parchment. Parchment making must have been very costly and perhaps the chief reason for his repeated bankruptcies. One bible with 1250 pages would have needed hundreds of animal skins and processing them likely hundreds people.

1. Is it know the type (which animal skins) Gutenberg used?

2. How many pages were printed on one sheet of parchment?

3. How much time, from slaughter to finish, is needed to produce parchment?

Sorry, I can’t answer your questions at this time.

parchment making technique and materials used to make a parchment in Ethiopia is different from European countries.

I think the techniques are very similar. I understand they do not use slaked lime to remove the hair. http://www.larkvi.com/mss/eth/production/parchmenting.php