Topics on this page:

Plant Factors Determining Disease Onset

To confirm the hypothesis that powdery mildew was being observed to start to develop in field-grown plants when they begin to produce fruit because this is a physiological stress that increases plant susceptibility, rather than that this corresponds to when inoculum of the pathogen becomes available, a replicated experiment was conducted with pumpkin seeded on different dates in 1993. The following image taken on 19 August shows the first plantings (oldest plants) white due to powdery mildew while youngest plants that haven’t started to produce fruit have no symptoms despite the quantity of spores present in the planting. This research is the basis for the recommendation to begin scouting crops for powdery mildew or start a preventive fungicide program when scouting isn’t feasible. An action threshold for starting fungicide applications of 1 leaf with powdery mildew symptoms out of 50 older leaves examined was identified and shown to result in powdery mildew being managed as effectively as using a preventive schedule (starting before symptoms seen).

Subsequently it was demonstrated that regularly removing fruit as they started to develop on a summer squash plant resulted in powdery mildew becoming less severe than on an adjacent plant with fruit harvested after they reached marketable size.

Twice powdery mildew was observed on young, pre-flowering cucurbit plants outside. Both cases the plants were stressed for reasons other than fruit production. One case the plants were in a very weedy field. The other was seedlings stressed having out-grown their seeding trays while hardening outside during a long delay before they could be transplanted. Once the plants started growing again after they were transplanted, powdery mildew did not develop on new leaves until couple weeks later when the plants started producing fruit.

However, cucurbit plants grown in a greenhouse or growth chamber are susceptible to powdery mildew from the cotyledon stage. Cotyledons are used to maintain isolates of the powdery mildew pathogen and to conduct laboratory leaf disk bioassays for determining fungicide resistance.

Publications (click on year to download):

- McGrath, M. T. 1996. Successful management of powdery mildew in pumpkin with disease threshold-based fungicide programs. Plant Disease 80:910-916.

Sexual Reproduction, Chasmothecial Formation, and Overwinter Survival

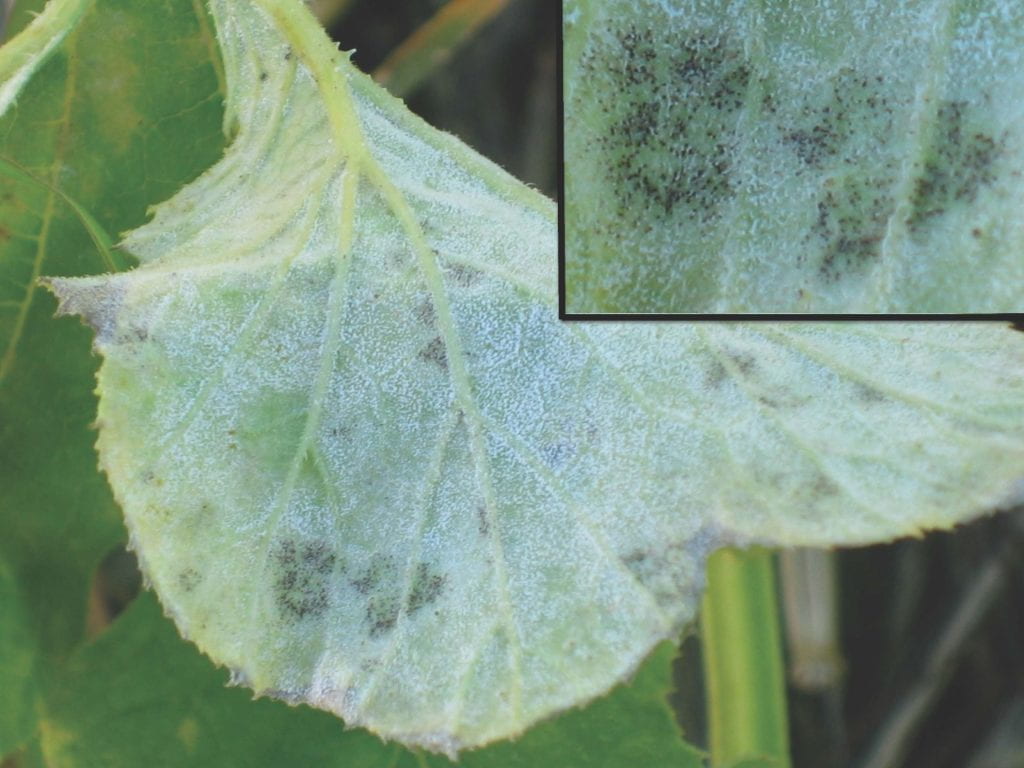

Chasmothecia were observed on cucurbit leaves during late summer to early fall. These tiny, brown, spherical structures contain ascospores that have capability to survive over winter because of the structure of chasmothecia.

Observing chasmothecia in a powdery mildew culture plate (cotyledon on water agar in a Petri dish) indicated that factors affecting their formation could be studied in the laboratory. First step was to determine whether sexual reproduction is required for chasmothecia to form (heterothallism), in which case chasmothecia only form when two fungal isolates of opposite mating type (fungal equivalent of gender) grow together. Some powdery mildew fungi are homothallic and can form chasmothecia without sexual reproduction. Isolates were inoculated in pairs on leaves in detached leaf culture plates. Chasmothecia formed only with some combinations of isolates and never in plates with single isolates, thereby confirming this pathogen is heterothallic.

Effect of temperature on chasmothecial formation was examined by inoculating leaves with pair of isolates that formed chasmothecia at room temperature, then keeping the leaves in incubators at different temperatures. The following image shows that chasmothecia formed in the plate kept at 20 C (right), but not the plate kept at 24 C (left).

Ability of ascospores to survive over winter was examined to determine if these spores could be a source of the pathogen for crops the next year. In fall, pieces of leaves with chasmothecia were put in mesh bags, placed on the soil surface or buried, and periodically over winter bags were removed and ascospores were examined to determine viability.

Proportion of ascospores that were viable declined over winter. While there were some viable ascospores the next growing season, they likely are not important in the pathogen’s life cycle in commercial production because chasmothecia need to be above ground to release ascospores into the air and tillage typically done to prepare fields for planting cover crop in the fall and the next crop in spring would move many into the soil. Additionally, fields usually are not re-planted to cucurbits thus ascospores would need to move further by wind to reach a host which is a chance event, plus the pathogen does not need ascospores because it produces a lot of asexual spores capable of long-distance wind dispersal to serve as initial inoculum. However, it could be significant if an ascospore of a fungal isolate with multi-fungicide resistance successfully is dispersed to and infects a cucurbit leaf. In contrast, chasmothecia of the grape powdery mildew fungus overwinter on canes and thus are quite close to leaves when they emerge.

Publications (click on year to download):

- McGrath, M. T. 1994. Heterothallism in Sphaerotheca fuliginea. Mycologia 86:517-523. (After this article was published the pathogen was renamed Podosphaera xanthii and the term cleistothecia was changed to chasmothecia.)

- McGrath, M. T, Staniszewska, H., Shishkoff, N., and Casella, G. 1996. Distribution of mating types of Sphaerotheca fuliginea in the United States. Plant Disease 80:1098-1102.