A Speculatory analysis of MLM diffusion in the context of COVID-19 Externalities

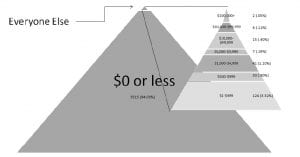

Multilevel Marketing Companies (MLM) are direct sales companies heavily structured around growing their network of distributors. Its premise is eerily similar to pyramid schemes: Distributers/recruiters are heavily encouraged to recruit new members via rewards based on commissions off of what their recruits buy and sell, in addition to retailing products to customers outside the distributer network through word of mouth. Not only are pyramid schemes and MLM incredibly hard to tell apart, but most MLM participants make next to nothing in earnings or even go bankrupt (see figure 1) (Bosley and McKeage, 2015; Multilevel Marketing Businesses and Pyramid Schemes, 2019).

Figure 1: A Speculatory analysis of MLM diffusion in the context of COVID-19 Externalities (Bosley and McKeage, 2015)

Despite their dismal statistical returns, MLM’s occupied 96% of the U.S. Direct Selling Association as of 2011 (Bosley and McKeage, 2015). Due to the similarities between MLM and Pyramid schemes’ practices and behaviors and the fact that many pyramid schemes masquerade as MLMs, I will be using the two terms synonymously for this essay’s purposes. In this paper, I would like to take a look at the spread of MLMs in the context of COVID-19. First, I would like to take a look at how multilevel markets diffuse through social networks. Then, using the data collected by Time Magazine and U.S. Federal Trade Commission 2020 MLM pandemic reports, I will analyze how COVID-19 may have produced an environment that encourages MLM growth(Gressin, 2020; Vesoulis and Dockterman, 2020).

- Multilevel Marketing: a predatory network model

The growth of an MLM’s distribution network follows a diffusion-of-innovation framework. Diffusion-of-innovation is typically used to describe the adoption of new ideas, services, and products. In MLM schemes, what is diffused through network structures is their unconventional or “innovative” business model. In fact, in a case study of the fraudulent MLM Fortune Hi-Tech Marketing by Bosley and McKeage, 85% of participants became direct sellers (or distributers) to earn an income while 9% of members joined for the product discount(Bosley and McKeage, 2015; Pang and Monterola, 2017). The fact that such a large majority of members joined to become distributors, compared to the relatively small portion of people that joined for the product discounts, shows that most people were interested in adopting the business rather than using the products.

Following the classical diffusion-of-innovation theory, in MLM’s, there are two kinds of adopters. Bosley and Mckeage refer to this as the work of “innovators” and “imitators.” Innovators are early adopters that join via mass-media communication, and imitators are late adopters that join via interpersonal interaction within semi-embedded social networks (Bosley and McKeage, 2015). In other words, innovators bring the MLM model into their social networks in which new imitators are produced via interactivity with the innovators and imitators.

In the interest of maximizing imitators, MLM’s will try to lower their adoption threshold. One of their most effective tactics is via interpersonal interaction in which recruiters are encouraged to tailor the appeal towards their social networks’ beliefs and desires. Bosley states that this kind of recruitment can range from in-person conversation to offering “training materials” in which MLM’s further attempt to lower the adoption threshold though emphasizing the “anyone can do it” mantra (Bosley and McKeage, 2015; Pang and Monterola, 2017). This practice is so persistent that the derogatory term “hunbot” is used to describe the recruiters in popular culture. The term references MLM members’ characteristic use of the slang word “hun” and their robotic persistence when searching for recruits(Urban Dictionary: hunbot, no date; r/antiMLM – FAQ, no date). Inevitably, ignoring externalities, innovation via mass media has its limits in its reach(Bosley and McKeage, 2015). Furthermore, by the nature of diffusion and adoption thresholds, adoption via imitators will eventually slow as network clusters saturate (We will come back to this idea later).

Unfortunately, like pyramid schemes–once an MLM network has saturated a social cluster, it is hard for existing members to renounce the organization when losing money (Anderson, 2004; Bosley and McKeage, 2015). One of the primary reasons is the high social cost of choosing to “switch” or leave the MLM in a, now, MLM saturated network structure. Bosley states that the price of participants denouncing the MLM is often too great as many face losing close friends made through the MLM, guilt for recruiting strong ties like family and friends into the same fate and/or shame for failing to make money(Bosley and McKeage, 2015). Thus, despite the high rate of failure among MLM participants, MLM schemes continue to spread among social groups.

- COVID-19 Pandemic Externalities and MLM Growth?

As I have stated before, when all else is held constant, MLM schemes’ adoption tends to slow as the market saturates. However, what happens to MLM membership in the presence of sudden traumatic externalities like the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and resulting job recession?

According to Pew Research, during the COVID-19 pandemic in May, the U.S. unemployment rate reached a record-breaking 13% pushing the country into another recession (Rakesh, 2020). According to data following the 2007-06 recession seem to show that recessions accelerate MLM’s as memberships rose from 15.1 million in 2008 to 18.2 million in 2014 (Vesoulis and Dockterman, 2020). Thus, we can speculate that the sudden uptick in people searching for jobs would bring in new opportunities for MLMS to adopt innovators that will rapidly adopt subsequent imitators. Unfortunately, the chance of innovative recruitment during this pandemic recession seems to not be lost on predatory MLM’s. In June the FTC warned of MLM’s using mass media and interpersonal messages to take advantage of the financially strapped state of many people. An example of such message is as follows:

Will you get a stimulus check? . . . [W]ould a extra $4,100 change your family lifestyle? Well my firm is offering that and more . . . Text Isagenix to [5 digit SMS text number](Gressin, 2020)

Thus, with MLM’s pushing such rhetoric in recruitment in addition to records of MLM resurgence during recessions, I believe that MLM memberships will rise following the end of this COVID-19 pandemic.

Sources:

Anderson, K. B. (2004) ‘Consumer Fraud in the United States: An FTC Survey’, p. 170. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/consumer-fraud-united-states-ftc-survey/040805confraudrpt.pdf

Bosley, S. A. et al. (2019) ‘Decision-making and vulnerability in a pyramid scheme fraud’, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 80, pp. 1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2019.02.011

Bosley, S. and McKeage, K. K. (2015) ‘Multilevel Marketing Diffusion and the Risk of Pyramid Scheme Activity: The Case of Fortune Hi-Tech Marketing in Montana’, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 34(1), pp. 84–102. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.13.086

Business Guidance Concerning Multi-Level Marketing (2018) Federal Trade Commission. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/business-guidance-concerning-multi-level-marketing (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

Gressin, S. (2020) FTC letters target more unproven MLM health and earnings claims, Consumer Information. Available at: https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/blog/2020/06/ftc-letters-target-more-unproven-mlm-health-and-earnings-claims (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

Multi-Level Marketing Businesses and Pyramid Schemes (2019) Consumer Information. Available at: https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/0065-multi-level-marketing-businesses-and-pyramid-schemes (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

Pang, J. C. S. and Monterola, C. P. (2017) ‘Dendritic growth model of multilevel marketing’, Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 43, pp. 100–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2016.06.030

Rakesh, K. (2020) Unemployment rose higher in three months of COVID-19 than it did in two years of the Great Recession, Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/11/unemployment-rose-higher-in-three-months-of-covid-19-than-it-did-in-two-years-of-the-great-recession/ (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

r/antiMLM – FAQ (no date) reddit. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/antiMLM/ (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

Urban Dictionary: hunbot (no date) Urban Dictionary. Available at: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=hunbot (Accessed: 16 December 2020).

Vesoulis, A. and Dockterman, E. (2020) Pandemic Schemes: How Multilevel Marketing Distributors Are Using the Internet—and the Coronavirus—to Grow Their Businesses, Time. Available at: https://time.com/5864712/multilevel-marketing-schemes-coronavirus/ (Accessed: 16 December 2020).