Playing the Climate Game: Prisoner’s Dilemma to a Stag Hunt

This article from The Atlantic takes a unique approach to outline a project on game theory and climate change. It considers three different games with scenarios including a hypothetical negotiation between the United States and China to reduce emissions. Although given real situations and their contexts, there will be infinite outputs for each player depending on various factors. However, for the purpose of simplification, there are two strategies and two outputs that are defined within the context of the game: coordination or defection and costs or payoffs.

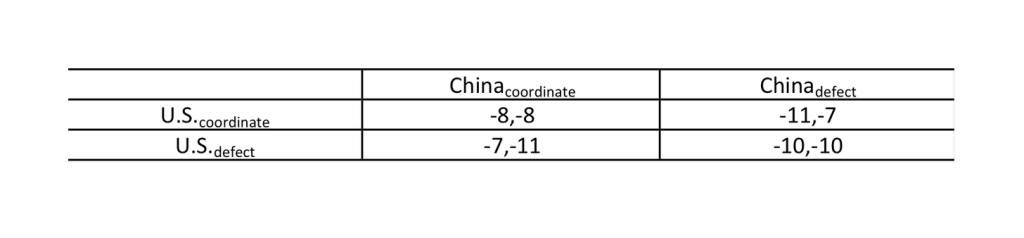

The model below estimates the overall costs of climate change to be a 10 on an arbitrary scale. It also assumes that each country’s emission efforts can reduce the costs of climate change by 3 points. For example, if the United States/China cuts emissions independently, the costs of climate change are reduced to 7. If both countries act, costs are reduced by 4 (each country’s costs are reduced by 2). However, emissions policies are also costly, and generally, if one player acts alone, the returns are low compared to the costs. To reflect this, the emission efforts will cost 4 so that it is more than 3: the benefit of one player’s contribution.

Overall, it is evident that the model suggests that the best overall option would be for the two countries to cooperate. However, the dominant strategy in a Prisoner’s dilemma (defined in the textbook and lecture) is the best choice for an individual player regardless of what the other player chooses. Therefore, the dominant strategy for both countries would be to defect (top right and bottom left cell) to avoid the potential dangers of acting alone and to gain benefits as the free rider without investing their time and money. If both countries choose the defect, they would continue to exploit the environment at the rate that they are now.

Given the fact that climate change becomes a more severe and immediate problem with relatively higher payoffs for small amounts of mitigations, the game has the potential to turn into a Stag Hunt. The Stag Hunt game, as discussed during the lecture on game theory, can be defined as a scenario where two players (hunters) will catch a stag (highest-payoff outcome) if they collaborate, but will catch a hare if they do not work together. If one hunter tries to catch a stag on his own, he will get nothing, while the other one can still catch a hare. If the two players choose different strategies, the one trying for the higher-payoff outcome gets penalized more than the one trying for the lower-payoff outcome. (In fact, the one trying for the lower-payoff outcome doesn’t get penalized at all.) As a result, the challenge in reasoning about which equilibrium will be chosen is based on the trade-off between the high payoff of one and the low downside of miscoordination from the other. Policy makers’ collective goal should be to turn the Prisoner’s Climate Change Dilemma into a Sustainable Stag Hunt before the problems we face today become irreversible. Therefore, policymakers should focus on collaborating to increase the payoff of sustainable efforts, reduce costs of carbon mitigation, and increase understanding of the inevitable consequences of climate change.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/04/climate-change-game-theory-models/624253/