The King of Oil: How a Powerful Network Position Led Marc Rich to a $2 Billion Profit

Marc Rich, born Marcell David Reich in Antwerp, Belgium, was one of history’s most prolific and most controversial commodities traders. Over the course of his 50-year career, Rich founded and built the company known today as Glencore: the world’s largest publicly traded commodities trader (Value Today), among others. Known for his cutthroat business acumen, Rich pushed the limits of what was legal in pursuit of profits, and in some cases, exceeded them. Listed among the “most wanted” by the US government for many years owing to alleged tax evasion and sanctions breaking, the former financial fugitive is perhaps best known for receiving a presidential pardon on Bill Clinton’s last day in office.

While Rich dealt with many controversial, authoritarian regimes, one of his most controversial and most profitable deals involved selling millions of barrels of Iranian crude oil to the apartheid South African regime over the course of the 1980s. Following Iran’s Islamic Revolution, the overthrow of the US-backed shah in 1979, and the seizure of the US embassy in Tehran soon after, the US government placed an embargo on Iran which barred companies from conducting many types of business with the country, including trading oil. Meanwhile, several thousand miles to the south, the Republic of South Africa had since 1977 been dealing with the consequences of sanctions initiated by the United Nations because of its discriminatory apartheid policies. While these didn’t explicitly bar sales of oil, the international community’s reluctance to do business with the racist regime led the country to become more and more isolated over time, culminating in US economic sanctions and an OPEC oil embargo in 1986 (Hefti and Staehelin-Witt). Thus, a situation presented itself in which one of the world’s largest oil producers was unable to sell much of its oil, while Africa’s wealthiest nation, with few fossil-fuel reserves of its own, had great difficulty finding any to buy.

As mentioned in Daniel Ammann’s “Iran Sanctions: The Sobering Lessons of Marc Rich,” Marc Rich and his company took great advantage of this situation, “at times making a profit of up to $14 per barrel” (Ammann). For context, the average price of a barrel of crude oil over the course of the 1980s was $25.51 per barrel (inflationdata.com). Depending on the true prices Rich and co. were able to negotiate (likely lower than average for the Iranian sellers and higher than average for the South African buyers), it is plausible that the profit margins on these deals were greater than 100%. In total, it is estimated that Rich and his companies made a $2 billion profit over 15 years trading oil by this route (Ammann).

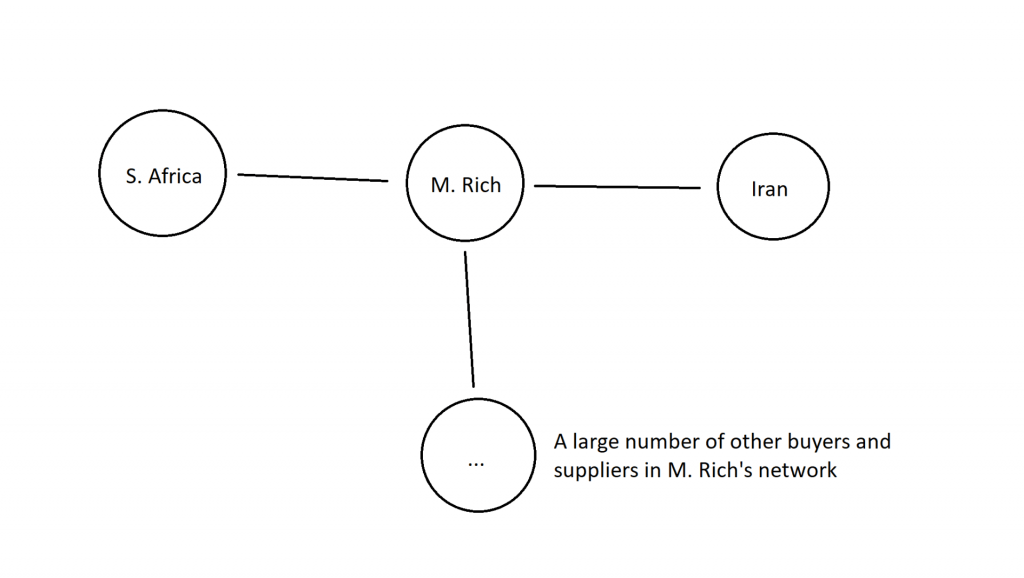

Thinking about this situation in the context of what we learned about bargaining and power in networks, the incredible profitability of these trades becomes less shocking. As the only large players in the oil market willing to risk the ire of the United States and OPEC (owing largely to their incorporation and operations being conducted from Switzerland), Marc Rich and his companies were in a near-perfect position to exert maximum leverage on their Iranian suppliers and South African buyers to trade oil with a massive markup. Intuitively, we would recognize the commodity traders in this situation as the “middlemen”; in graph theory, we could show this relationship network with the following graph, with M. Rich as a middle node:

In this setup it is easy to understand the traders’ leverage. They have the four key principals of power in social networks working in their favor: dependence, exclusion, satiation, and betweenness. Owing to the sanctions placed on both nations, South Africa and Iran were highly dependent on Marc Rich to buy/sell oil. This allotted M. Rich power as he and his companies could exclude Iran from being able to sell a large portion of its oil production and/or exclude South Africa from receiving oil, both of which would be highly detrimental outcomes for those regimes. M. Rich and co. also gained power from the principle of satiation; as the commodity traders also had access to a large network of other oil buyers and suppliers, they could have threatened to buy it from sources other than Iran if Iran hadn’t offered a very competitive deal while threatening to sell their oil supplies to countries other than South Africa if South Africa hadn’t offered a very high price. In both cases, M. Rich had the liberty to choose only the most profitable deals to conduct while the two countries didn’t, giving M. Rich a great deal of leverage. Finally, M. Rich benefitted greatly from the principle of betweenness. He and his companies were directly between the two countries in the transaction. The legal environment meant that there were no other traders involved who might also have negotiated a cut of the profits, while Rich and co. themselves couldn’t have been cut out as neither Iran nor South Africa had the legal nor logistical capabilities to facilitate this trade directly. Using the great leverage this one man was able to exert over two nations, Marc Rich and his network of companies pulled off one of the most profitable commodities deals in history.

Mentioned Article:

Ammann, Daniel. Iran Sanctions: The Sobering Lessons of Marc Rich. March 2010. <https://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/iran-sanctions-sobering-lessons-marc-rich/story?id=10118387>.

Other Sources:

Hefti, Ch and E Staehelin-Witt. “Economic Sanctions against South Africa and the Importance .” Schweizerischer Nationalfonds (2011).

inflationdata.com. Historical Crude Oil Prices (Table). October 2021. <https://inflationdata.com/articles/inflation-adjusted-prices/historical-crude-oil-prices-table/>.

Value Today. World Top Commodities Trading Companies List by Market Cap as on Sep 1st, 2021. September 2021. <https://www.value.today/world-top-companies/commodities-trading>.