Reflecting on the “Greatest Pandemic in History”

With COVID-19 continuing to spread quickly across the globe, it seems logical that many have begun to take a much deeper look at the deadliest pandemic disease in recorded history. The likely ill-named, “Spanish Flu” began its spread in 1918, during a period of great global conflict. It is believed to have taken the lives of over 50 million people or 5% of the world’s population at the time. In a period with significantly less advanced medical technology than today, the spread of the disease was contained by employing several methods, some of which seem to have had little positive impact, and some which are eerily relevant due to their aid in stopping the virus progression.

Looking back at the Spanish Flu becomes even more insightful when examined alongside the branching process model we studied in class. The branching process model allows us to predict a R0, or the basic reproductive number, which provides a prediction about whether a pandemic will be contained or spread until the entire population has been infected. R0 is determined by multiplying k, the number the people each node in the network encounters per wave by p, which represents the likelihood of someone spreading the disease to the nodes they have had contact with. If RO is less than 1, the pandemic will not infect everyone. If it is greater than 1, there is a non-zero probability that it will infect everyone.

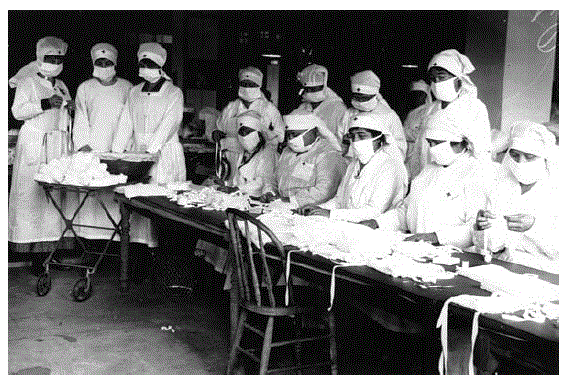

Applying this model to the Spanish Flu, we see that the World in 1918 either made changes to society that moved p and k, and thus R0, such that it was less than 1 or they got very lucky. Moving p was difficult due to the medical technology of the day. Without anti-viral medications or vaccines, medical professionals and businesses may have inadvertently raised p by suggesting remedies which we now know to have negative effects on those suffering from viruses. They however, succeeded in lowering p by advocating for something now familiar, face coverings. In comparison to today and the COVID-19 pandemic, there is hope for a much less deadly virus as leaps in medical technology will likely allow us to lower the p in the pandemics branching process model.

The medical professionals and policy makers of 1918 succeeded in correctly implementing measures to reduce k, long before the prevalence of the branching process model. In Chicago and other cities, they closed theaters, movie houses, and prohibited public gatherings. In other cities across the world they advocated for quarantine of the sick, reduction in public transportation use, and dedensification of clusters of people. All of this sounds familiar because these measures to some degree were successful in reducing k and stopping the spread of the virus. Hopefully with measures like this k and thus, R0 for COVID-19 will drop well below 1.

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/pandemic-timeline-1918.htm

https://www.livescience.com/spanish-flu.html