Coffee Trade and Network Exchange

Coffee is one of the most popular products worldwide. It is used in various kinds of foods and beverages people consume every day. It is a multi-billion dollar industry that spans every corner of the world. There are more people than you think out there who can’t begin their day without a smooth, creamy cup of coffee. Provided the immense amount of money that flows into big coffee corporations like Starbucks and Folger, one would be surprised to know that the farmers and workers who process these plants hardly make any money despite contributing a major role in the production line. It is evident that revenue distribution is tremendously polar and exploitation in human labor is indubitable. Companies based in the United States import coffee from countries in South America, Africa, and etc only to keep most, if not all, the benefit to themselves. It is said that millions of African family farmers are facing economic devastation and the African production market loses $1.47 billion annually due to exploitation[2]. How can that be?

It has been determined that more than 70-80% of the coffee is produced by small-scale farmers [1]. Some even produce less than a person would drink in a year. On the contrary to cultivation, the number of businesses that are in charge of processing, marking, and distribution is significantly lower, essentially creating an oligopoly. It is determined that around 40% of the world’s coffee is roasted by just three companies and five companies control over half of the coffee in trade (from 2014)[1]. Such a consolidation trend has only continued.

I believe that the giants in the coffee industry have so much power in trades because they have such a big connection network to suppliers. In addition to their economic scale, there are very few competitors. These companies are said to employ a strategy of extending payment terms to a few months with farmers to further gain an edge in the market to out-compete the smaller-scaled companies that engage in fair trade[1]. These farmers have no choice but to accept these predatory contracts.

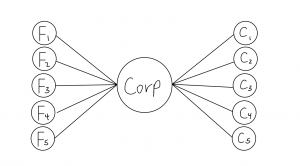

Such a relationship between farmers and mega-corporations resembles the network exchange graphs covered in class. As demonstrated in the figure below where the nodes from left to right are respectively farmers, big corporations, and consumers, we can see that the big corporations are connected to a lot more nodes than the other two groups, giving them a lot more power in terms of trade. I am primarily focusing on the farmers here as buying coffee products is a freedom of choice for consumers. Farmers face a situation where they are not satisfied with the disproportional amount of reward for the work they put in, but they do not have the means or power to alter the course. First of all, farmers can’t compete with big corporations. In addition, most of them are not educated well enough or have no resources to engage in policy or political work to convert the status quo. The fact that farmers are scattered all around the globe as individuals only help corporations. Secondly, farmers don’t have the option to drop out of farming coffee since it most likely is the family’s only source of income and the only thing they can do to make a living. In essence, the farmers are trapped, falling victim to the coffee empire that reaps the fruit of their hard work. It is under my impression that one of the reasons for this unfairness is due to the outsourcing of coffee production on top of insufficient protection from international coffee trade policies for the farmers. Not to mention the immaturity of labor rights and protection from these local areas. These make farmers in those countries targets of the coffee business.

Note here in a simplified model I have constructed, the consumers and farmers have essentially a value of zero for their outside options. Meanwhile, the corporations, as the middleman, controls the trading network. In equilibrium, the corporation gains a benefit of approximately one (it has an outside option of one) while the farmers gain a benefit close to zero. That is the Nash bargaining solution for the model. It can be seen that if a farmer disagrees with the terms listed by the corporation, the corporation will simply turn to another farmer since there are so many suppliers. This will leave the farmer out of income, forcing them to compromise. The vicious cycle of exploitation continues.

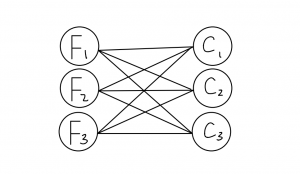

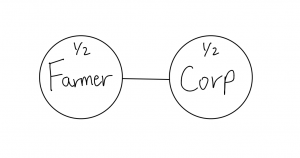

One of the potential solutions I believe is shown here in another simplified network I’ve included: this time, the corporation, or the middleman, is removed, and farmers can directly interact with consumers. Without a centralized institution, each node is free to trade with any other node on the other side. The result is that power is relatively equally distributed across the network and no one party dominates. Another potential solution can be that farmers cooperate together to form a union where they collectively deal with the corporations, this way, it would be one giant node on the farmers’ side instead of many. Hence, the power of corporations will be greatly reduced and equality can be attained as their interaction is basically a two-node trade where both nodes have an outside option of zero. Then, both sides gain around a portion of one half in exchanges. In reality, I suspect that policies should be taken place to constrain the dominance of these mega-businesses for the sustainability of farmers as well as the coffee industry itself.

I find it extremely helpful to think about the trade and economic activities in terms of network exchanges where power is relative and depends on the underlying connections themselves. As in the case of the coffee industry, the graph can easily explain who dominates the trade. It is clear why corporations have such an upper hand against the farmers and what can be done to prevent such exploitations. It is fascinating to visualize all the relationships between nodes and what implications each leads to. Furthermore, an important insight I’ve acquired is that power doesn’t solely rely on your position and connections, but also depend on the status of others in the network. Overall, I see how network exchange can model many situations whenever relative powers are the subject of interest.

Article 1: https://fairworldproject.org/low-prices-and-exploitation-recurring-themes-in-coffee/

Article 3: https://fairworldproject.org/starbucks-has-a-slave-labor-problem/