How Homophily in Social Networks Perpetuates Inequality

How Homophily in Social Networks Perpetuates Inequality

In this article, Matthew Jackson, a Stanford economist examines how human network effects can perpetuate inequality in society. Jackson asserts that “In almost all professions, a high percentage of jobs are found via referral.” This mirrors Granovetter’s study in the 1960s which concluded that most people got their job through personal contact. However, the Granovetter study also found that for most people who found a job through personal contact, this individual was only an acquaintance, not a close friend. Thus, both Jackson and Granovetter similarly come to the conclusion that the composition of your friend circle, comprised of weak ties, which are acquaintances, and strong ties which are close friends heavily influence whether you will get a job or not.

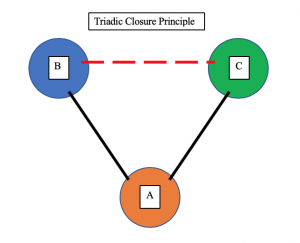

On the other hand, Jackson heavily stresses how homophily, or the tendency of individuals to create bonds with people who are interested in similar things, perpetuates inequality as people tend to self-segregate themselves into different clusters depending on their homophily to similar individuals which in turn leads to homogenous demographics in particular employment positions. The idea of homophily that Jackson discusses relates to the Triadic Closure Principle or the idea that if two people have a friend in common, they are more likely to be friends themselves (as shown in the diagram below). Thus, clustering of groups with homophily can lead to demographic, “especially by ethnicity and gender” (Jackson) inequalities between groups.

Jackson asserts that in order to counteract the inequality perpetuating side effects of homophily in social networks, we must design infrastructural institutions that mitigate clustering effects. In other words, we must design for social impact. In smaller groups, such as local high schools, students are pushed to seek friendship and form stronger ties with people outside their own racial group as there are a smaller amount of people available within their own racial group; thus, promoting less homophily.

Jackson’s analysis of the job referral market shines a light on how homophily and the clustering principles of the Triadic Closure Principle could have potentially negative side effects. We commonly examine who we include in our social networks but commonly forget that who we exclude from social networks can experience the loss of shared benefits and knowledge found within social networks. Furthermore, how we construct algorithms on social networks which determine who is a weak or strong tie with one another can determine long-lasting and long-reaching real-world consequences. Thus, we must first become aware of the negative consequences that homophily in social networks can have, and secondly, try to structurally mitigate the negative effects of homophily through social network infrastructure design.

Works Cited

De Witte, Melissa. “How Human Networks Drive Inequality, Social Immobility.” Stanford News, 6 Mar. 2019, news.stanford.edu/2019/03/06/human-networks-drive-inequality-social-immobility/.