Antibiotic and Anti-viral Stewardship

August 2022. Contributed by Faith Meza

Antimicrobial Stewardship in the health care setting is typically considered when antibiotics are used only when necessary and appropriate for treating bacterial infections. When an animal companion is brought into a veterinary clinic and presents symptoms such as lack of appetite, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and other signs of infection, veterinarians tend to treat them with antibiotics. Veterinary medical professionals worldwide use antibiotics to help fight bacterial infections, but what happens when we over prescribe antibiotics to animals that do not have a bacterial infection? A few things can happen when animals are given antibiotic medicines they do not need, including developing drug resistance. Bacteria can evolve to resist commonly prescribed medications, leading to the development of bacterial strains that do not respond to antibiotic treatment. There are certain situations where antibiotics can be given to patients fighting viral infectious diseases to help treat secondary bacterial infections. However, in these situations, antibiotics do not target the virus itself, but are active against bacteria that have taken advantage of the animal’s weakened immune defenses as it fights off the virus. In these cases, viral infections can negatively affect the immune system’s ability to fight off other infections. Bacterial culture is recommended as a best practice to determine the appropriate medication to administer when a patient is displaying a bacterial infection.

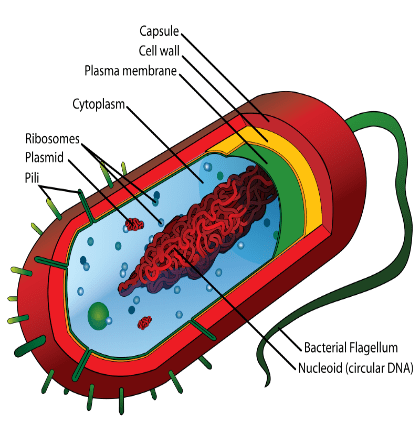

To fully understand how antibiotics treat bacterial infections, it is essential to understand the basic structure of a bacteria cell. Evidence shows that bacteria existed as long as 3.5 billion years ago, making them one of the oldest living and abundant organisms on Earth. From the graphic, the structure of a bacterial cell can be seen. Bacterial cells comprise a a capsule, cell wall, plasma membrane, cytoplasm, ribosomes, plasmid, and pili, which together make up a bacterial cell, with the cell wall the most important for the diagnostic work up that bacterial infections typically get.

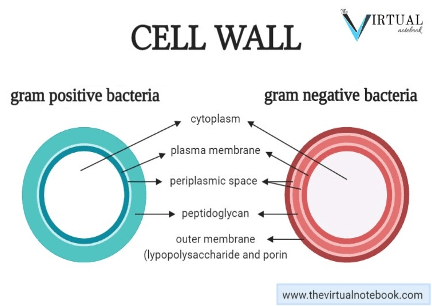

A foundation of diagnostics for a bacterial infection, is to determine if the infection is a Gram-Negative Bacterial Infection or Gram-Positive Bacterial Infection. To determine if the bacteria you are dealing with is Gram- Positive or Gram-Negative, staining can be done to determine the gram-status of the bacteria. The class of Gram-positive includes the entirety of genera Staphylococcus and some of the Listeria. One of the easiest ways to distinguish the Gram-Positive bacteria is that it will have a very apparent purple appearance after staining. In contrast, the Gram – Negative bacteria will have a pale reddish color. So why is knowing the difference between Gram- Positive and Gram-Negative bacteria so important? Identifying the differences in the type of bacteria is essential to determine the right course of antibiotics to help fight off the bacterial infection. For example, if the bacterial stain comes back as Gram-Positive, you can use Amoxicillin, Ampicillin, and or Cefazolin as a treatment option. While if the bacterial color comes back as Gram-Negative, you can use Ormetoprim, Tetracycline, or Trimethoprim-sulfonamide as a treatment option. Understanding the difference between Gram-Positive and Gram- Negative bacteria is beneficial to finding the proper antibiotic treatment for your animal companion.

option. While if the bacterial color comes back as Gram-Negative, you can use Ormetoprim, Tetracycline, or Trimethoprim-sulfonamide as a treatment option. Understanding the difference between Gram-Positive and Gram- Negative bacteria is beneficial to finding the proper antibiotic treatment for your animal companion.

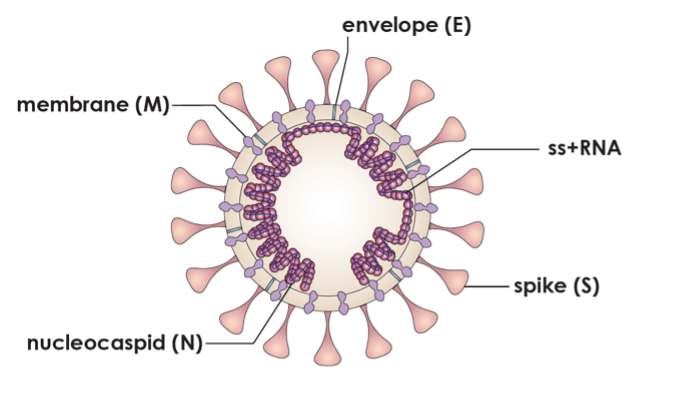

However, antimicrobials are much more than antibiotics; they are medicines used to treat and prevent fungal infections, parasitic infections, and also viral infections. In the Whittaker lab, we study viruses and think a lot about antivirals and antiviral resistance. As with antibiotics for bacterial infection, viruses can and do become resistant to drugs too—and resistance can occur readily, especially for RNA viruses which are error-prone in their replication and generate many variants during a course of disease. Feline coronavirus is a major focus of the lab and is the cause of FIP (Feline Infectious Peritonitis), one of the most significant and problematic infectious diseases of cats.

Coronavirus Schematic

There are now several ways to treat FIP in cats, using the new anti-viral drugs that are becoming available, but as with antibiotics it is essential to use the right drug at the right time. One of the new drugs is called GS-441524, which acts as analog of one the building blocks of RNA during replication and interferes with infection. It is not without its concerns though, including that it is currently not approved by the FDA to be used in the United States; see our earlier post at: (https://blogs.cornell.edu/fightfip/fip-antivirals/). Its widespread but unregulated use, combined with the fact that is a ‘monotherapy’ means that antimicrobial resistance is a significant potential concern. For other RNA viruses where effective antivirals exist (such as HIV and hepatitis C in humans), long-term success only came with “combination therapy” (the use of more than one drug each having a different target), combined with good diagnostics and wide-ranging partnerships to bring costs down and deliver the drugs to those in most need.

There are now several ways to treat FIP in cats, using the new anti-viral drugs that are becoming available, but as with antibiotics it is essential to use the right drug at the right time. One of the new drugs is called GS-441524, which acts as analog of one the building blocks of RNA during replication and interferes with infection. It is not without its concerns though, including that it is currently not approved by the FDA to be used in the United States; see our earlier post at: (https://blogs.cornell.edu/fightfip/fip-antivirals/). Its widespread but unregulated use, combined with the fact that is a ‘monotherapy’ means that antimicrobial resistance is a significant potential concern. For other RNA viruses where effective antivirals exist (such as HIV and hepatitis C in humans), long-term success only came with “combination therapy” (the use of more than one drug each having a different target), combined with good diagnostics and wide-ranging partnerships to bring costs down and deliver the drugs to those in most need.

Antimicrobial Stewardship requires the clinician to collect evidence that a specific infectious agent infection is present before drugs are prescribed. As an example, when a cat shows symptoms of an upper respiratory disease (sneezing, watery eyes, fever, lack of appetite), it can be diagnosed with rhinitis/sinusitis/conjunctivitis or inflammation of the nose/sinuses/and eyes. The most common causes of rhinitis in cats are viral, including feline herpes virus and feline calicivirus. More rarely, the primary reason is bacteria such as feline chlamydia. The involvement of a trained clinician and a diagnostic lab are critical as only chlamydial infections would responsive to antibiotics, and in these cases, tetracycline antibiotics are the antibiotic of choice because they are most effective against this type of infection. Antiviral treatment for feline herpesvirus does exist, but must be timed appropriately dosed appropriately based on the virus life-cycle and risk of complications. Feline calicivirus treatment is purely supportive.

As new antimicrobials become available for bacteria and viruses alike, it is paramount to ensure good stewardship of these drugs. This involves a robust pipeline of new drug candidates to allow combination therapy or as treatment alternatives, good clinical care from a veterinarian and the use of validated and targeted diagnostic tests.

A special thanks to DVM Stephen Dean Wilkinson with Animal Haven Veterinary Clinic for helping with the post.