Introduction

Through a partnership with Cornell’s Law School and Al-Marsad, our team was able to learn more about the issues in the Golan. Three main stories were particularly significant—the land mines planted throughout the region, the wind-farm project, and the forgotten occupation of Golan by Israel. In our ideating and brainstorming, we identified two problems—that the Syrian population in the Golan is unknown to many, and that many activists fighting for Syrian voices in the Golan are losing hope in the initiative.

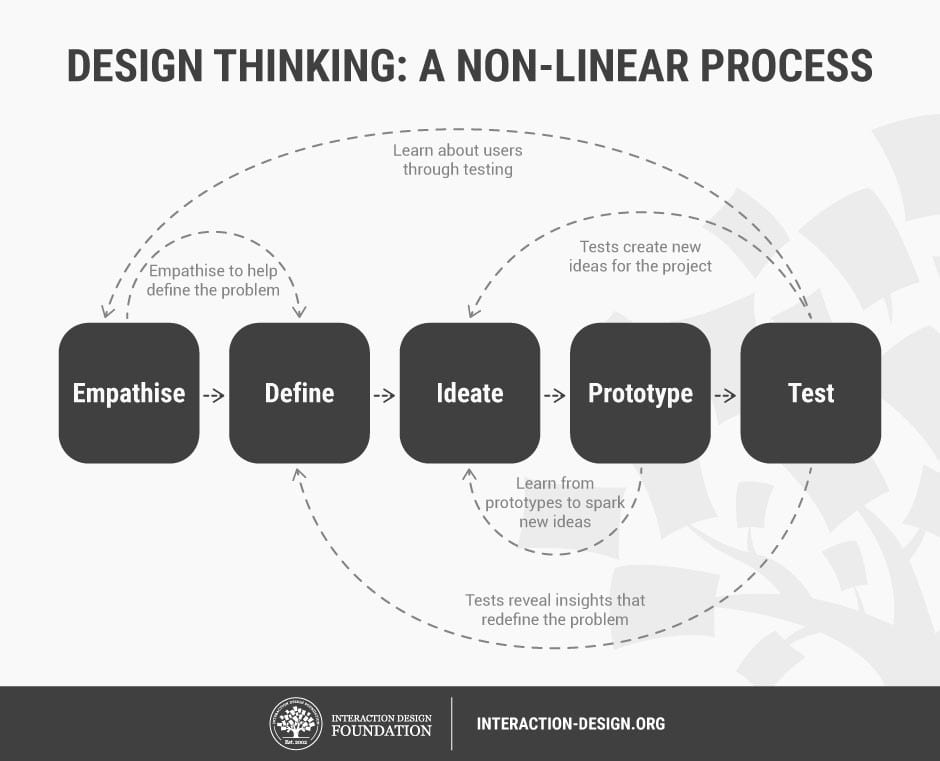

We will use the Design Thinking framework to outline our semester’s work with Al-Marsad. With a project of this magnitude, linear progress was not expected. What others might refer to as setbacks, Design Thinking encourages and builds into its process.

What is Designing Thinking?

Context

The Golan Heights is a plateau of fertile farmland overlooking both Israel and Syria. Israel captured this region from Syria in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community recognizes the Golan Heights to be official Syrian territory and widely rejects Israel’s military occupation of the Golan. Israel and the United States of America (the Trump Administration) are the only two states that recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights. Through meetings with Al-Marsad, our main stakeholder, we were able to learn more about the issues in the Golan. The prototype that we are producing for Al-marsad is a storyboard for a short transmedia film, from 5 to 10 minutes. Through these materials, the central issues that constitute the narrative of the forgotten Golan, which are interconnected with each other through the theme of “land”, starting with the 1967 war and the occupation of the Golan, then displacing people from their lands, destroying their villages and farms, confiscating lands and establishing settlements on the ruins of these villages, the legislation of the law to annex the Golan Heights, the imposition of civil laws that ended the stage of military rule, and the attempt to impose Israeli citizenship, by force, on the residents of the Syrian Golan. Controlling the land with mine laying and exploiting the natural resources of the Golan, preventing the Syrian population from communicating with their families in their mother country – Syria, canceling the Syrian educational curriculum and replacing it with Israeli curricula that seek to engineer a new identity for the Golan residents, centered on their sectarian identity and cut off from its Arab cultural roots. Down to recent years that witnessed the imposition of discriminatory local council elections – which distorted the democratic idea – and finally the wind turbine project.

Initial Design Challenge

Al-Marsad wants a Social Media Campaign in order to raise awareness in the international community and publicize the cause and effects of construction of wind turbines on occupied land.

Team

Al-Marsad

Al-Marsad – Arab Human Rights Centre in Golan Heights is an independent, not-for-profit international human rights organization with no religious or political affiliation that operates in the Golan Heights.

Our Team

Process

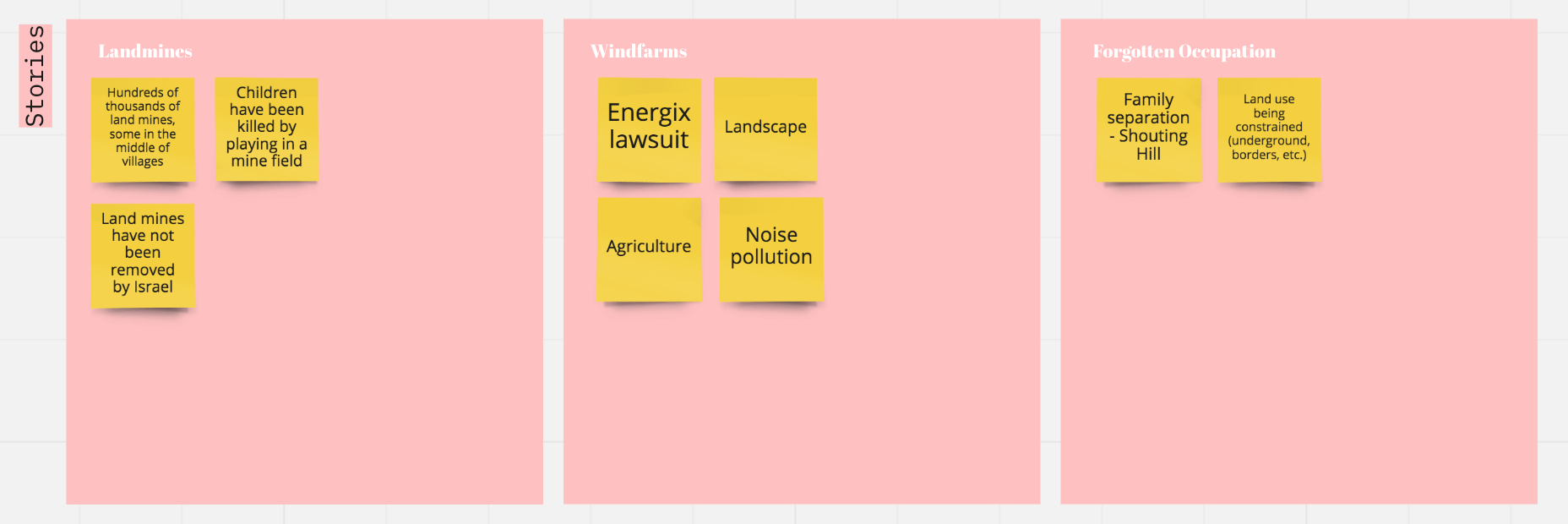

Empathize

Initially we wanted to better understand the history behind Golan and be able to empathize with our users. After reading numerous documents given by our stakeholder, Al-Marsad, we organized it in sticky notes and extracted a number of keywords. From our empathizing stage, we identified three significant stories: land mines, wind-farm project, forgotten occupation of Golan by Israel.

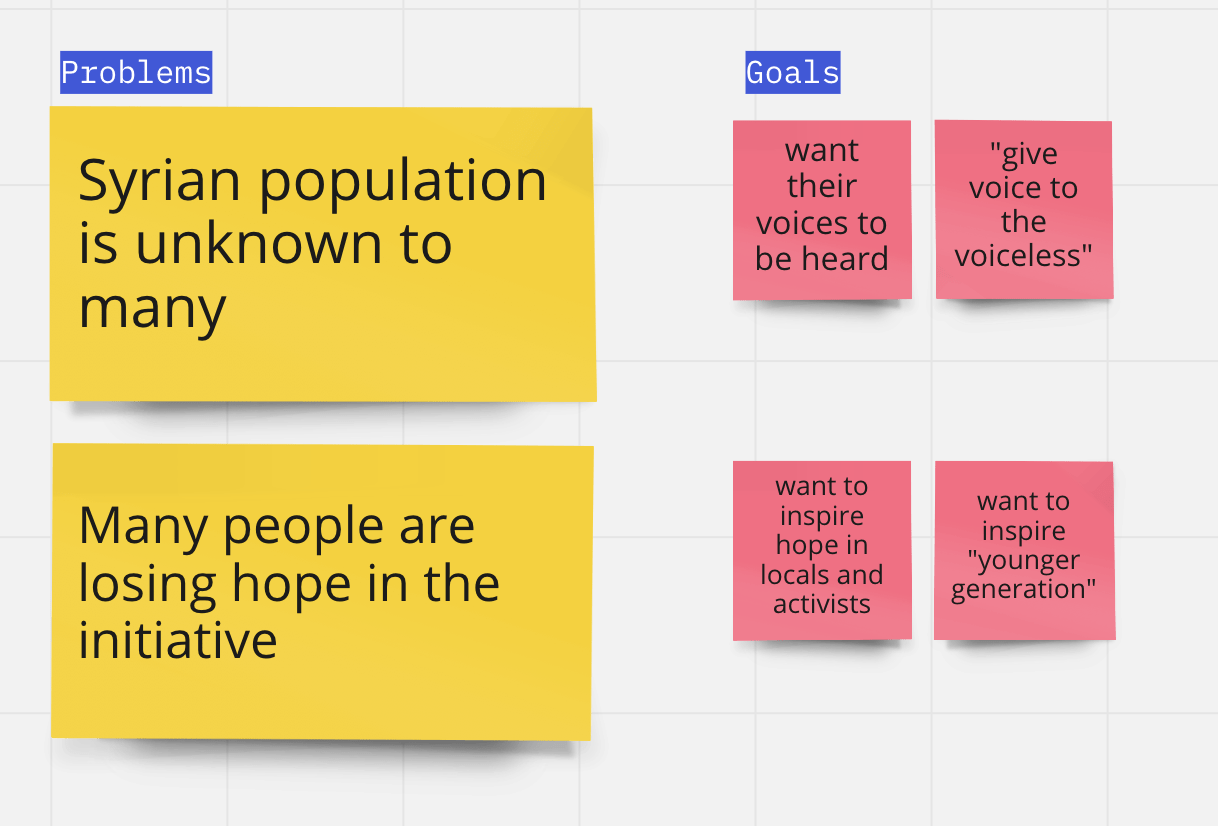

Define

From here, we were able to reach two problem statements: the Syrian population in the Golan is unknown to many, and many activists fighting for Syrian voices in the Golan are losing hope in the initiative. We defined our goals, which are to let Syrian voices be heard (to “give voice to the voiceless”), to inspire hope in locals and activists, and to inspire the younger generation internationally.

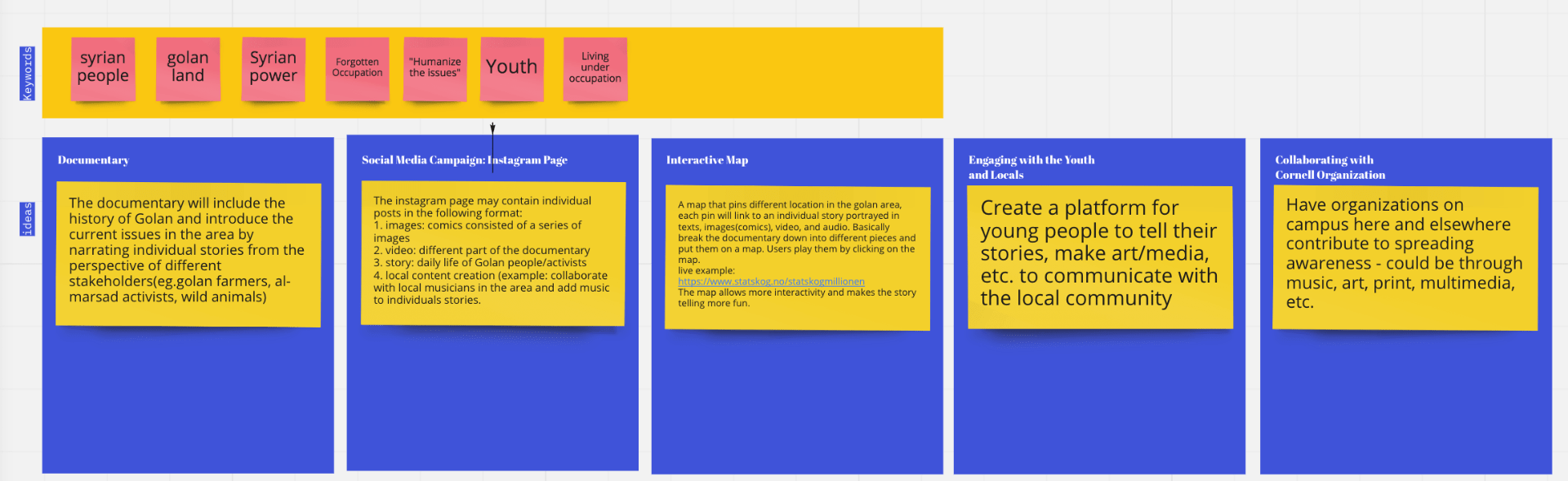

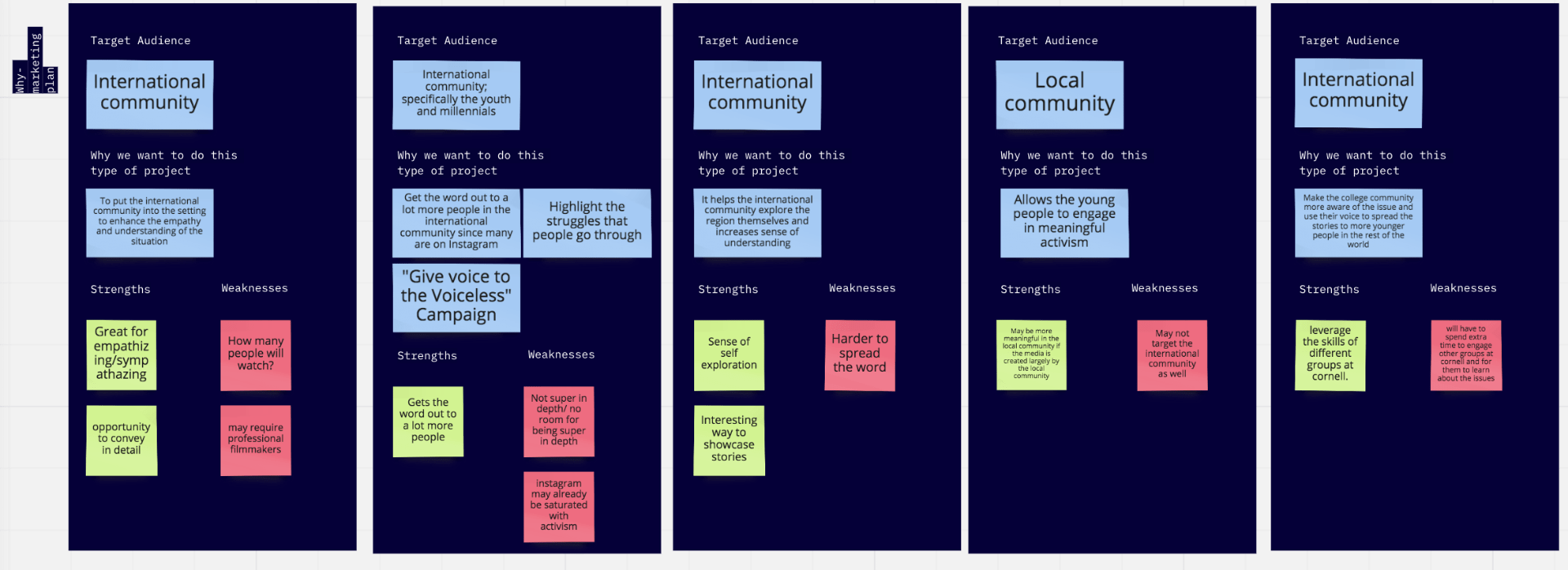

Ideate

Our goal was to amplify the voices of local residents of the Golan as well as inspire activists and the younger generation to keep fighting. We came up with five ideas: a documentary, a social-media campaign, an interactive map, engagement with the youth population and locals of the Golan, and collaborations with Cornell organizations. With the exception of the fourth idea, which would target the local community, the ideas would be aimed toward engaging the international community with the hopes of raising awareness to the issues surrounding the Golan and telling the stories of those affected.

First Ideation

Second Ideation

Third Ideation

Prototyping & Testing

First Iteration

We then started to focus on storyboarding the transmedia film. Our first storyboard was much broader in scope, where we focused on different issues in the history of the Golan that related to the theme of land, with each scene placed on a map to illustrate how the landscape of the Golan has changed over time during the continued occupation. Each scene would be separate, with the map tying it all together, though we also thought about incorporating personal anecdotes and interviews into some scenes.

However, our stakeholders thought this would be too broad and too long, and viewers would not want to spend more than 5-10 minutes watching a video. Our stakeholders pitched the idea of the short film being narrated by Amir, whose story we focused on in a scene showing the deadly landmine problem in the Golan. They wanted Amir to be a narrator/character who would travel backward and forward through time and be inserted into the history of the Golan Heights, and this would be the major unifier of all the separate scenes in the film.

Second Iteration

We took this feedback and created a second storyboard meant for a much shorter (2-3 minute) video with more dramatic impact. The film would tell Amir’s story, and through it, the issues in the Golan heights would be highlighted. It would show Amir before, during, and after the 1967 war, and how the culture and landscape of the Golan changed when the Israeli occupation began. Amir’s death, when he steps on a landmine, would be the emotional climax of the film, and the film would end on a plea for the landscape of the Golan not to be changed even more through the building of wind turbines on the land.

Our stakeholders were in favor of focusing on the landmines and tracing the historical events that led to their placement on Golan land. The story board began with the war of 1967 and eventually made it to the present day. However, our stakeholders thought it was unclear how Amir would transition from an omniscient narrator to a character and how we would signal to the audience what years we were in, especially since Amir lived a few decades after the war, and the culture of the Golan had already changed. Thus we decided to use Amir’s father as a narrator for the early years, which would make the timeline easier to follow and contrast between his childhood circumstances and Amir’s.

Final Deliverable

Experience Design

This storyboard uses juxtaposition to emotionally affect the audience and highlight the changes that have occurred in the Golan in the last 60 years. In its current form, the innocent, sketched figures represent innocence, which contrasts the tanks, protests, and landmines in some of the scenes. The dialogue is sparse, which emphasizes an image-based experience of the storyboard. These scenes will transition rapidly from shot to shot. We were unable to complete the short transmedia film during this semester, but the final product will add chaos to the viewing experience by zapping from scene to scene.

Information Architecture

The storyboard begins with Amir, a boy living two decades after the 1967 war, who is playing happily in a field and talking with his father. However, the story then shifts to Amir’s father’s childhood and his experiences of life before the Israeli occupation and of war. The story shifts back to Amir, and parallels are drawn between their lives—they play in the same field, they go to the same school, but things are different (e.g., what was once taught in Arabic is now taught in Hebrew). These parallels are structured so that they are noticed gradually—we are first immersed in Amir’s childish innocence, which turns into dawning comprehension as the scenes unfold and the viewer sees his father’s history. However, the viewer still thinks that the changes, after the war is over, are mostly cultural. Then the landmine scene occurs, when Amir dies while playing with his friend, which shocks the viewer. The following scenes are structured after the emotional climax in order to inspire activism, and show both Amir’s father protesting the occupation of the Golan and a grown-up Yasmin looking at the wind farms being built.

Information Design

The first two scenes, which focus on Amir, are happy and carefree, and are meant to evoke a childish innocence, though his stepping in cow waste is a foreshadow of darker things to come. The first two scenes of Amir’s father’s memory, likewise, are brighter and more carefree, with the father doing normal activities, such as playing and going to school. Ghost-Amir and ghost-father smile when they see the scenes play out in front of them. However, the scene shifts dramatically when the war comes, and we see ghost-Amir as well as his young father’s fear. The lighting is darker, and the sounds of bombing and screaming are ominous. In the next scene, when his young father is being separated from his family, the characters are scared but also sad, and the emotional impact of the occupation on the Syrian citizens is seen. When the next scene shifts back to Amir going to school, it is a bright day, but the innocence is no longer there, and the many symbols of Israel are prominent.

The next scene is the landmine scene. It starts out more carefree, as Amir plays with his friend and chases the butterfly, but the camera cuts out suddenly as he stumbles onto the landmine. The next several seconds are silent, as the camera lingers on the explosion; then, the camera focuses on the butterfly, which lands slowly. The gravity of what happened should be impressed upon the viewer. Finally, the last two scenes are somber. The scene of Amir’s father protesting is rainy and miserable, as people shout in the background and his father cries. The last scene shows grown-up Yasmin and her son looking at the turbines with curiosity and apprehension, as the boy does not know what is happening, but Yasmin knows that this is another tragedy for the Golan. These scenes are designed to elicit sympathy for these characters as well as a call to action.

Report PDFs

Video