Monitoring Wildlife in the Peruvian Amazon

Location: Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve

It sounds cliche, but my experience in Peru was actually one of the most rewarding and enriching experiences I’ve ever had. I began this experience not fully knowing what to expect. As any wildlife enthusiast would, I had googled the animals and plants of the Amazon for the months leading up to trip (perfect procrastination fodder for finals week). I had read the trip brief through and through. From movies and books, I had this perception of the Amazon jungle as this impenetrable, mysterious wilderness with jaguars slinking from trees and piranha lurking it its waters, and I was unsure how a group of Earthwatch citizen scientists fit into this whole picture.

That being said, the wildlife did not dissapoint! I’ve never seen such an explosion of life. Coming from someone who grew up camping in deserts where all life seems to hide in shaded cracks and under rocks until dusk, it was incredible to be in a place where life had so visibly found a way to jam itself into every single possible square inch. None of the surveys ever got dull because there was always a new or interesting bird or plant to admire.

But despite the fact that the wildlife was spectacular, probably the most striking part of the Amazon for me was the amount of human life on the river. As we went up and down the river, we passed ‘taxi’ boats, long canoes, and tourist vessels. Once we were in the reserve, we mainly saw the motor-powered wooden canoes of the rangers and inhabitants of the area. We often passed small villages of brightly colored stilted houses, one of which was even loudly blasting cumbia music. You’d think that even with my three years of environmental science training I wouldn’t forget how ‘pure wilderness,’ untouched by humans is pretty much a myth, and not a very helpful or good myth at that. This is not any less true for the Amazon, considering that about 20 million people call the Amazon Basin home. The nature documentaries, photos and national geographic wonderfully document the wildlife of the Amazon, but they do not do justice to the people who have also adapted to the Amazon environment, with its fluctuating wet and dry seasons, and who have carved out their own piece of the Amazon to carry out their livelihoods and raise their families.

The very photogenic Euclides paddles one of the canoes during our fishing survey. PC Joseph Zegarra Liao

On the Earthwatch expedition, we were privileged to have indigenous Cocama scientists on our team. They have such an intimate knowledge of the forest and wildlife, pointing out monkeys in the trees that I would have never seen on my own and mimicking the sounds of monkeys and birds with uncanny accuracy. I was lucky enough to get to set out the fishing nets with Euclides (pictured right) and go pole-fishing with him afterwards while we waited to check the fishing nets (as dictated in the fish survey protocol). In the time that I caught two of the wimpiest looking piranhas ever seen, Euclides had caught what seemed like 20 fish. Watching Tulio machete his way through the forest or capture a meter long caiman with his noose was like watching a biologist action hero movie. Euclides, Tulio and Samuel have a skill-set and knowledge of their surroundings that I aspire to! Of course for many people in the Amazon, these skills are a necessity to live off of the forest, but this doesn’t make these skills any less impressive…especially to an outsider like me.

It was really interesting comparing wildlife management in the Amazon with that of the United States. Wildlife managers in the US do have to balance the needs of wildlife and people like hunters and recreationists, but most of the US population does not depend on wildlife wholly for subsistence. With the Amazon it is a slightly different story; the health of wildlife populations is directly tied to the health and welfare of the people who depend on these resources. (Though it is true that in the US there are many farmers and forest managers who deal with wildlife issues affecting their crops/animals and therefore their livelihoods, but overall, most of American wildlife management deals with recreationists and non-subsistence hunters.)  Because people’s stake in wildlife is much higher than let’s say nuisance raccoons in NYC, Amazonians are more invested in the sustainability of wildlife populations. At the same time, people have also been less willing to follow wildlife regulations when it prevents them from feeding their families. In any situation, wildlife management is a tricky and complex field; balancing the needs of a healthy ecosystem and the equally important needs of healthy, happy communities is far from easy. Fortunately, in many parts of the Amazon, including the Pacaya-Samiria Reserve, park officials and scientists are working with local community members to determine wildlife population levels and the appropriate hunting levels. From surveys like the ones we conducted and by gathering information from hunters, scientists are able to get better estimates of the health of wildlife populations, and in turn are able to work with locals to identify what percentage or amount of a species can be hunted sustainable.

Because people’s stake in wildlife is much higher than let’s say nuisance raccoons in NYC, Amazonians are more invested in the sustainability of wildlife populations. At the same time, people have also been less willing to follow wildlife regulations when it prevents them from feeding their families. In any situation, wildlife management is a tricky and complex field; balancing the needs of a healthy ecosystem and the equally important needs of healthy, happy communities is far from easy. Fortunately, in many parts of the Amazon, including the Pacaya-Samiria Reserve, park officials and scientists are working with local community members to determine wildlife population levels and the appropriate hunting levels. From surveys like the ones we conducted and by gathering information from hunters, scientists are able to get better estimates of the health of wildlife populations, and in turn are able to work with locals to identify what percentage or amount of a species can be hunted sustainable.

The process is way more complicated and difficult that I am writing here, but I think this system is moving in a positive direction, especially compared to times and places where wildlife has been historically hunted to near extinction when there has been no control or where authoritative systems have led to major conflicts between local people and park administration. While the world often thinks of the Amazon as this place that is being ruthlessly deforested and ruined, there are actually many really inspiring projects going on in the Amazon where people are working to create sustainable relationships between the river and forest and people. Like the blurb for the documentary Amazônia eternal says, “the Amazon is a vast laboratory for sustainable experiments that are revealing new relationships among human beings, corporations, and the natural heritage crucial for life on the planet.” Also, I would recommend the documentary. It is quite good and has some great cinematography.

The process is way more complicated and difficult that I am writing here, but I think this system is moving in a positive direction, especially compared to times and places where wildlife has been historically hunted to near extinction when there has been no control or where authoritative systems have led to major conflicts between local people and park administration. While the world often thinks of the Amazon as this place that is being ruthlessly deforested and ruined, there are actually many really inspiring projects going on in the Amazon where people are working to create sustainable relationships between the river and forest and people. Like the blurb for the documentary Amazônia eternal says, “the Amazon is a vast laboratory for sustainable experiments that are revealing new relationships among human beings, corporations, and the natural heritage crucial for life on the planet.” Also, I would recommend the documentary. It is quite good and has some great cinematography.

Overall this experience made me think differently about how I approach wildlife management and conservation, especially as an aspiring and emerging wildlife science professional. Being on an Earthwatch expedition opened my mind to the idea of conservation research as a business model, with many of my thoughts paralleled by my predecessor Sinan. While I left feeling excited and inspired by the promising projects in the Pacaya-Samiria Reserve, I also left with a heavy heart because I really did fall in love with the Amazon forest and animals and the lovely people I met on this trip. The other volunteers on this trip were such good-hearted people. While I was fortunate to go on this expedition on a scholarship, most of the other volunteers had decided to donate their time and money to support conservation research. While we always think of natural and social scientists and activists and policy makers as the ones saving our planet, we can’t forget the non-scientist/activist/policy makers who may not be directly working to protect our environment, but are doing so in their own ways like supporting programs like Earthwatch.

I would like to thank Muriel K. Horacek for funding this incredible opportunity for me and other Cornell students in honor of her late husband, Fred Horacek. I would also like to thank Steve Morreale for overseeing this partnership between Cornell and Earthwatch (and being the best advisor ever), the incredible researchers and staff on the Rio Amazonia, my fellow Earthwatch volunteers, and all the lovely people I met during my time in Peru.

Now what Amazon trip would be complete without a slew of wildlife pictures! Thank you to Joseph Zegarra and Kathy Savage for allowing me to use your photos since I am photographically-handicapped.

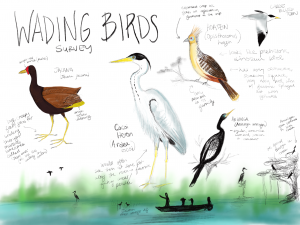

And a couple more sketches

Howler monkeys up in the canopy.

Howler monkeys up in the canopy.