Our Goals and Methods:

How the Cornell University & Indigenous Dispossession Committee Determined which Present-Day Nations and Communities have been Affected by Cornell’s Past and Present Land Manipulations

by Kurt A. Jordan, Dusti C. Bridges, and Troy A. Richardson

October 17, 2023

Introduction

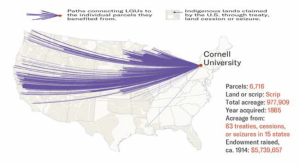

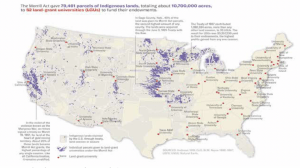

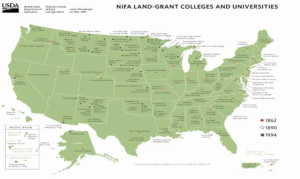

In June 2020, faculty and staff in Cornell University’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) formed a committee to assess the responsibilities and obligations Cornell has to Indigenous peoples based on its actions as a Land Grab/Land Grant institution.[1] The Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession (CU&ID) committee first committed to inform affected Indigenous Nations about the connection between Cornell and their homelands, in the hope of generating a broad-based coalition of Indigenous governments to engage with Cornell President Martha Pollack. Secondly, the CU&ID committee sought to build on the efforts of the authors of the March 2020 High Country News (HCN) “Land-Grab Universities” report to provide each Indigenous Nation with the specifics of how Cornell benefited, and continues to benefit from, their loss of lands and waters. Third, the CU&ID committee developed and presented a set of recommendations to President Pollack regarding internal processes through which the institution can pursue relations of responsibility for the benefits accrued as a result of dispossessed and stolen land.

Beyond this, the CU&ID committee has and continues to assert that it is imperative to act in consultation with the Indigenous Nations and communities affected by Cornell’s actions. While there are policies and practices the Office of the President can and should enact as a show of good intentions, the CU&ID committee hesitates to provide or impose plans on Indigenous Nations without full consultation; imposed plans and policies for Indigenous Nations have a long history of failing miserably that AIISP does not wish to replicate. AIISP has developed and pursued program-to-Nation diplomatic outreach, working toward a coalitional project seeking restorative justice for Indigenous peoples affected by Cornell’s actions.

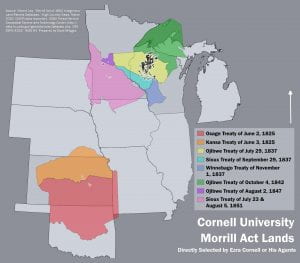

A first step in the process of diplomatic outreach was to examine the history of Cornell’s role in dispossession more closely. The CU&ID committee’s stated goal of “advocating for redress” required a complete list of communities affected not only by dispossession associated with the Morrill Act of 1862, but Cornell’s present-day land holdings throughout New York State and elsewhere. To determine which Nations and communities have been affected, the project used the data and GIS resources provided by HCN, along with resources spanning from 19th century ethnographies to modern social media to compile the list.

It should be noted that AIISP and the CU&ID committee have taken a broad view of what constitutes an affected community in our diplomatic outreach effort. We know that many Indigenous communities have lost federal recognition due to the extreme colonialist impacts that they have suffered over time. In some senses, communities without recognition have been most affected by colonialist institutions, including Cornell University. Thus we have reached out equally to federally-recognized, state-recognized, and unrecognized groups that have been impacted by Cornell’s past and present actions. Similarly, we recognize that some communities whose traditional territories are in what is now considered to be the United States were displaced into what is now considered to be Canada. We acknowledge that dispossession does not stop at present-day international borders, and have reached out to Indigenous Nations in Canada that were historically entangled with Cornell.

Lastly, we view Cornell’s territorial machinations of all sorts as equivalent– we see no practical or ethical difference between lands directly owned by Cornell and properties on long-term leases; no difference between formal Cornell properties and those of affiliate units like Cornell Cooperative Extension; and no difference between Morrill Act lands directly acquired and managed by Ezra Cornell and his associates and those lands where Mr. Cornell sold scrip to speculators before individual parcels were officially located and “entered” (to use the Morrill Act terminology for claiming a particular parcel of land). All of these actions dispossessed specific Indigenous Nations and communities to Cornell’s benefit. Those communities deserve to be notified about this history of entanglement with Cornell, and provided with an opportunity for their voices to be heard about how to move forward.

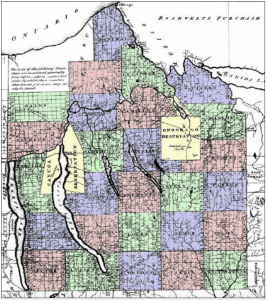

Compiling a List of Affected Communities

The Land Parcels Database generously provided by the HCN team formed the basis for our efforts to determine which Nations and communities had been, and continue to be, affected by Cornell’s actions.[2] HCN supplied shapefiles and table data that include the locations and attributes of parcels of land associated with the Morrill Act. For each parcel, this data included three key attributes: the university to which the parcel was attached; how the land was taken from its Indigenous occupants (e.g., through treaty, outright seizure, etc.); and what community the lands were attributed to at the time of dispossession (most often the signatories of associated treaties). This data, coupled with a map of land cessions provided by the USDA Forest Service Geospatial Service and Technology Center, [3] allowed us to compile a list of nations historically attributed to the land of each parcel.[4]

On the surface, this endeavor might seem to be a straightforward investigation of the connections between the signatories of the treaties and their contemporary descendants. However, several complicating factors soon arose. Treaties between North America’s Indigenous peoples and colonizing entities are not known for their integrity—corruption, coercion, and misrepresentation were common. We found that some of the treaties in question excluded communities whose lands most definitely were affected—where the U.S. opted to treat with only selected nations as representing everyone in the area. This meant that the signatories of treaties themselves were registers of dispossession. In one instance, the official signatories of the unratified 1851 Treaty at Camp Klamath that seized a portion Wiyot territory (which eventually came to include a Cornell parcel) did not appear to include any Wiyot representatives. This was due to a series of massacres and forced relocations that removed the Wiyot communities from the area prior to the treaty—a circumstance that certainly does not negate Cornell’s ties to Wiyot dispossession, as a simple signatories-to-contemporary nation list would imply.[5]

To explore these historical complexities and ensure that our list of affected communities was as complete as possible, we consulted the map of Indigenous territories produced by Native Lands Digital.[6] The Native Lands Digital map compiles Indigenous sources and historical research to display the general outlines of Indigenous traditional territories.[7] As an ongoing project, this map is continually updated with new sources and information, and is not meant to serve as a definitive set of boundaries. In fact, what one might consider an Indigenous community’s territory is more fluid than a linear boundary. The Native Lands Digital map was employed as a guide to flag any instances where dispossessed communities were underrepresented in the treaty process.[8]

One particularly challenging area of work were those parcels within the present-day state of California. The wide cultural and linguistic diversity of the region, coupled with small political units, settler ignorance (willful or otherwise), and widespread genocidal violence against Indigenous peoples in the area during the 19th century resulted in incomplete and inconsistent records of treated peoples that do not map easily onto present-day communities. The signatories of the California treaties ranged from individuals to community names and broader cultural groups. Furthermore, following these treaties, many communities were forcibly combined and rearranged into settler-defined Rancherias and reservations. The notes of late-19th century scientist C. Hart Merriam were an unexpected and invaluable resource in untangling these threads. Although Merriam’s focus was the study of animals in the West, he took meticulous notes on the Indigenous peoples of California, recognizing their knowledge of the wildlife and landscape he was studying. Merriam’s notes encompass Indigenous language dictionaries, placenames, maps, and a study that links signatories of the California treaties to their communities and broader cultural groups.[9] These notes, coupled with the Native Lands Digital map, allowed us to connect the historically dispossessed peoples to contemporary Indigenous Californian communities. To further connect these and other treaties to contemporary nations, we used a combination of directories provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Tribal websites, social media pages, news articles, and history books.

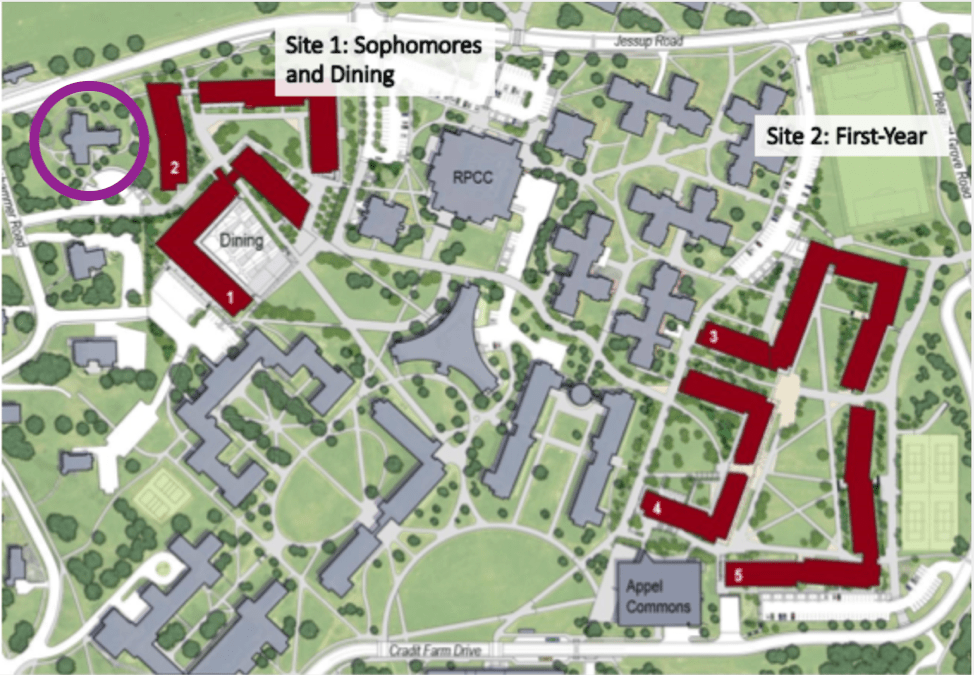

In the end, a combination of GIS, historic and contemporary maps, treaty documents, historic accounts, ethnographies, crowdsourced lists, Tribal websites, social media, and news outlets informed our list of contemporary communities whose ancestral land provided the financial foundation of Cornell University through the Morrill Act of 1862. Further, Cornell’s literal foundation – its present-day land holdings and educational outposts — span the length of New York State and include spaces in both Washington D.C. and Maine. Some of the communities affected by Cornell’s physical footprint are currently embroiled in struggles to maintain land in their homelands.[10] Communities upon whose land Cornell buildings and programs reside in our eyes have equivalent status to those Nations affected by the Morrill Act processes and their traditional territories and histories and were investigated using similar methods.

Our research to date demonstrates the fluid nature of our knowledge—new discoveries, implications, and connections will likely expand this list in the future as we continue to uncover the role of Indigenous dispossession in the university’s history. In particular, our focus moving forward has shifted to locating those land parcels where the university retains mineral rights, as well as any communities impacted by soldiers schooled through the military training requirement for male Cornell students that was mandated in the Morrill Act. These next steps may be particularly difficult as the Cornell central administration has informed the CU&ID committee that it will not supply a list of all of Cornell’s present-day landholdings to the group.

The Diplomatic Outreach Process

To begin contacting the affected nations, we drew upon formal and informal sources to collect physical and email addresses for the leadership of each community. For federally recognized nations, contact information was drawn from the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Tribal Leaders Directory and corroborated through individual nation websites.[11] For others, the most up-to-date contact information was gathered from a variety of sources. Some communities maintain websites and social media, while contact information for others had to be drawn from petitions and letters of intent to petition for recognition filed with the federal government. For some smaller communities, especially in California, this information could only be found readily available in Tribal consultation lists developed by local Cultural Resource Management (CRM) firms.

As we determined Nation and community addresses, we gradually sent out paper letters to each. Since these letters represented program-to-Nation diplomacy, we addressed them to the principal leaders in each Nation. We elected to use paper letters as they provided an element of formality that is lacking in electronic communication. In several instances, our first letters were returned as undeliverable by the Post Office. In those cases, we searched for additional addresses and mailed new letters. In relatively few cases, we resorted to email communication when letter deliveries to several addresses failed. We recognize that using paper letters alone may not have gained the attention of all addressees, but we hope that publication of the list of affected communities will provide another way of notifying leaders and communities of their entanglement with Cornell.

We recognize the research skills, logistical efforts, and attention to detail of numerous faculty, staff, and students associated with Cornell’s AIISP whose dedicated labor made the diplomatic outreach efforts possible. In particular, we thank Karishma Bottari, Dusti Bridges, Kurt Jordan, Leslie Logan, Ben Maracle, Ula Piasta-Mansfield, Troy Richardson, and Annabel Young.

[1] Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, “Land Grab Universities: Expropriated Indigenous Land is the Foundation of the Land Grant University System,” High Country News, March 30, 2020, https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.4/indigenous-affairs-education-land-grab-universities.

[2] Robert Lee, “Morrill Act of 1862 Indigenous Land Parcels Database,” https://github.com/HCN-Digital-Projects/landgrabu-data, High Country News, March 2020.

[3] “Tribal Ceded Lands,” USDA Forest Service Geospatial Service and Technology Center, 2018, http://data.fs.usda.gov/geodata/edw/datasets.php.

[4] For any institutions or individuals who wish to engage in these processes themselves, we have provided detailed instructions in the notes. To generate the initial map, Bridges first pulled CSV and shapefile data from the database provided by HCN. To assign the attributes listed in the CSV file (which listed attributes such as the University involved, the Patent date, amount paid, etc.) to the polygons representing each parcel within the shapefile, Bridges performed a table join using a unique object key within both files.

(using QGIS) Processing > toolbox > Join Attributes by Field Value > select the shapefile as input layer 1 and the CSV file as input layer 2 > set the table field for both inputs as OBJECTID_1 > set the join type as one-to-one > click run

To separate out the Cornell parcels from the rest, Bridges selected within the parcels shapefile by attribute, resulting in a new shapefile that only contained Cornell University Parcels.

(using QGIS) right click on layer > open attribute table > select/filter features using form > in the University field, type and Select Cornell university > click select features > close > right click on the layer in the layers panel > export > save selected features as > set the format to ESRI Shapefile > use the button with three dots to locate the file you wish to save to and name the file > make sure the CRS is correct for your project > deselect any unwanted fields > make sure the add saved file to map box is checked > ok

(note: it is also possible to use the Extract by Attribute function in the processing toolbox to complete this task, but these extra steps allow one to check the attribute table before generating a new shapefile from the selection. This can help catch any features that would be excluded due to typing and spelling errors, especially when dealing with a large amount of qualitative data.)

To add treaty boundaries to the map, Bridges pulled the “Tribal Ceded Lands” file from the USDA Forest Service Geospatial Service and Technology Center. To reduce the clutter on the map to treaties involved in Cornell’s parcels, Bridges extracted a shapefile of only the relevant treaties.

(using QGIS) Processing > toolbox > Extract by Location > select the Tribal Ceded Lands file in the “Extract features from” drop-down menu > select intersect under the “Where the features (geometric predicate)” heading > in the drop-down menu under “By comparing to the features from,” select the file containing the parcels you are studying > click run to generate the new file > this will create a temporary layer that you can save once you’ve double-checked the results (alternatively, navigate to the desired folder and name the file prior to running the extraction)

[5] Malloy, Kerri J. “Remembrance and renewal at Tuluwat: Returning to the center of the world.” In Remembrance and Forgiveness, pp. 20-33. Routledge, 2020.

[6] Native Land, Native Land Digital, 2021, native-land.ca.

[7] See https://native-land.ca/resources/ for a brief explanation of their methods.

[8] From the API page of native-lands.ca, (https://native-land.ca/resources/api-docs/), right click on “Territories” under the Files heading, and click save link. Save the link to a local file. The file will save as a .JSON. To add the file to your map in QGIS, navigate to the add vector layer window and add the .JSON file.

(using QGIS) layer > add layer > add vector layer > vector dataset(s) = (the indigenous territories JSON you just saved) > add

The individual territories are added to the map, but are not classified. To mimic the presentation of the Native Lands interface, change the display settings by right clicking on the layer in the layers panel.

(using QGIS) properties > symbology tab > select “categorized” in the drop-down menu at the top > select “name” in the drop-down menu for column > click on the symbol box to open the symbol selector box > set the opacity to 30% > click ok > click the classify button > click ok if a high number of classes warning appears > click ok to save the settings and exit the properties window

Your map should now look similar to the native lands site. Each parcel now intersects with one or more of the traditional territory polygons. One can now perform a spatial join to add these attributes to the parcel data, but we found that to be an unnecessary step when it came to this analysis.

[9] Merriam, C. Hart. C. Hart Merriam papers. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://lccn.loc.gov/mm82032698.

[10] For example, see Wolkin, Kenneth, and Joseph Nevins. “‘No sovereign nation, no reservation’: producing the new colonialism in Cayuga Count(r)y.” Territory, Politics, Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 42-60.

[11] U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Tribal Leaders Directory, https://www.bia.gov/tribal-leaders-directory

Jon Parmenter is an Associate Professor of History at Cornell University. During the 2022-23 academic year he will be a faculty fellow at the Cornell Society for the Humanities, focusing on the theme of

Jon Parmenter is an Associate Professor of History at Cornell University. During the 2022-23 academic year he will be a faculty fellow at the Cornell Society for the Humanities, focusing on the theme of