Blog post by Rebekah Elizabeth Ten Hagen, ’23

This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

This Guatemalan huipil (figures 1-6) was given to Charlotte Conable and her husband, Barber Conable Jr. ‘42, 7th President of the World Bank, as a diplomatic gift from the Guatemalan government. According to Mrs. Conable’s donor form, the couple was on a diplomatic visit to Guatemala, likely September 21st, 1987, early in Mr. Conable’s tenure as president. On this date, officials from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) met with Latin American, Spanish, and Filipino finance officials in Guatemala City in anticipation of the yearly meeting between the IMF and the World Bank (Neagle). The gift would likely have been presented to the Conables by the President of Guatemala, Vinicio Cerezo.

Barber Conable Jr. was a graduate of Cornell, earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1942 and his law degree in 1948. Charlotte Conable, née Williams, graduated from the College of Home Economics (now the College of Human Ecology) in 1951. Charlotte Conable was notable in her own right, earning a name for herself as an advocate for women’s rights and other issues. She published the book Women at Cornell: The Myth of Equal Education in 1977. Clearly, the Conables were an engaged and prominent couple.

Diplomatic gifts can give a lot of insight into a country’s culture, government, and values, so the gift of a huipil is significant. Firstly, it is a woman’s garment; while other traditional male garments exist which could be gifted, this piece is notably for a woman and shows the officials recognized Ms. Conable’s importance. Additionally, the garment is very traditionally Mayan, so in offering something with a Mayan history, Guatemala was recognizing the importance of the Indigenous population. The designs on huipiles are also rich in symbolism, which I will interpret later. Finally, the gift of a huipil is significant, as the garments are extremely labor intensive and may take months to create each one, which also means that genuine huipiles tend to be expensive to purchase.

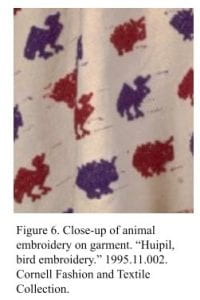

Huipiles are woven garments, created almost exclusively by hand using a backstrap loom (Martínez). Huipiles are usually made using one, two, or three panels. Though three panels is the most common formation, this huipil is made with two woven panels. Once the panels of the garment are woven, they are hand-embroidered (see embroidery in figure 6). The design motifs are created using a supplementary weft, which means the shapes and design elements depend upon the foundation structure of the plain weave and appear from disjointed points, much like a pointillist painting. Though the designs are created through point, huipiles overall are arranged very linearly, with patterns usually creating lines, and almost always adhering to a grid-like structure. Huipiles’ designs are very rarely of an organic nature.

There is much to be said about how the creator of this particular huipil utilized the various principles and elements of design to create a dynamic and meaningful piece. The most obvious use of line in the garment is the purple horizontal lines on the red portion of the body, but all of the embroidered designs are roughly linear; that is, the animals embroidered on the white part of the huipil are arranged in lines, and the diamonds are embroidered in a grid-like pattern (see figure 5).

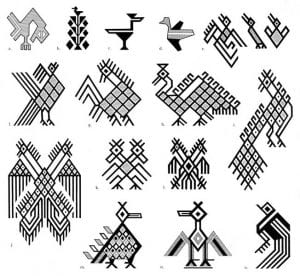

As mentioned, huipiles’ designs are highly symbolic, as the garments have been used by Mayans for thousands of years as sacramental/ceremonial articles, and the pieces can also be used as means of record-keeping. This particular huipil includes many commonly-used Mayan symbols in its supplementary weft designs. On the top half of the panels and on the back side, there are clusters of multi-colored diamonds (see figure 5). Diamonds are traditionally used to represent “the four corners of the universe or the sun’s path in the sky” (Martínez). There are two types of animals woven repeatedly on

the bottom-front of the garment (see figure 6). Though it is not completely clear what the animals are, it appears as though one is some type of bird, and the other is a type of mammal. Birds are often used in huipiles, and the way they are rendered and the type of bird can be significant in interpreting their meaning (see figure 7). It seems like the birds here are probably a poc duck (see figure 8), which is a type of duck native to Guatemala, but they might also be turkeys, which are an important part of various Mayan rituals and are valued highly (Martínez). The colors used in the weaving are also very significant. This particular huipil is color-blocked with a red upper section and a white lower section. The color red symbolizes energy and power, and the color white represents spirituality and the intangible (Martínez).

With the symbolism, design elements, and context of the gift, I believe this huipil was given to the Conables as an acknowledgement of the work the World Bank does to bridge transnational barriers and serve all the world’s population. The colors red and white seem to represent an omnipresent power, while the bird––whether a native Guatemalan duck or a ceremonial turkey––is a highly symbolic and significant creature. The garment itself is an homage to both Guatemalan history and Mrs. Conable’s work as an advocate for women’s issues.

Rebekah Ten Hagen ‘23, from Princeton, NJ, is a junior in the College of Industrial and Labor Relations, pursuing minors in Economics, Information Science, and Business. Rebekah has a passion for studying the culture of fashion and the relationship between cultural and economic factors and fashion trends. Rebekah is also serving as the President of the Cornell Panhellenic Council.

References

Looper, Matthew G. Gifts Of The Moon: Huipil Designs Of The Ancient Maya. San

Diego Museum Of Man, 2000.

Martínez, Armando. “Textiles of Guatemala: Symbolism behind the Huipil.” Casa De

Los Gigantes, 11 May 2020, https://casadelosgigantes.com/blogs/home-decor/textiles-guatemala-symbolism-behind-huipil.

Mayén, Guisela, et al. Confradia: Mayan Ceremonial Clothing from Guatemala.

Edited by Marty Davidsohn and Dina Fernández Garcia. Translated by Marianne Krieger de Quesada and Michael Twohig, Museo Ixchel Del Traje Indîgena De Guatemala, 1993.

Neagle, John. “Finance Officials Meet In Guatemala To Prepare For Annual

IMF-World Bank Joint Meeting.” Latin America Data Base, 22 September 1987.

Ortiz, Alejandro. “Un Mundo de Símbolos en Textiles Mayas”. Prensa Libre, 2021,

https://www.prensalibre.com/revista-d/un-mundo-de-simbolos-en-textiles-mayas/.

Rittmeyer, Miriam. “The Huipil: An Everlasting, Indigenous Cultural Emblem.”

Phalarope.org, Phalarope.org, 8 Feb. 2021, https://www.phalarope.org/magazine/2021/1/30/the-huipil-an-everlasting-indigenous-cultural-emblem.

“Teaching The Maya Resource – Design Motifs”. Mexicolore.Co.Uk, 2014,

https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/maya/teachers/resource-design-motifs